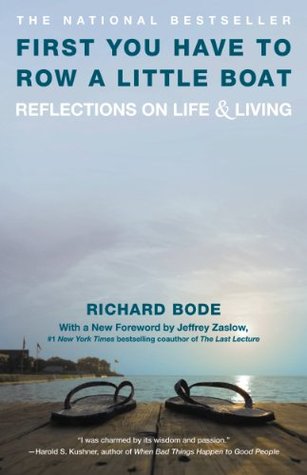

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Richard Bode

Read between

June 25 - June 29, 2020

my children weren’t born to learn from my experiences; they were born to learn from their own, and any attempt on my part to substitute my perceptions for theirs was doomed to fail.

What I didn’t know is that we grow toward our desire in the same way a flower grows toward the sun. We gain our ends not through seizure but affinity.

When we kill the dream within us, we kill ourselves, even though the blood continues to flow within our veins.

The games we play, the games that command our everyday attention, do so for reasons we often fail to see. Baseball and football are our national fictions for the simple reason that they’re accurate representations of truth about the life we live. A runner on second must advance to third before he can score, even though the fastest way home is a diagonal through the heart of the diamond over the pitcher’s mound. The most direct route from the line of scrimmage to the end zone is straight ahead, but it’s a rare touchdown that’s made that way; there are too many would-be tacklers between the ball

...more

Above all else, the nature of our existence demands that we master reality.

In sailing, as in life, momentum is a valued commodity, the secondary source of power that keeps us going long after the original source has disappeared.

I’m no more protected in my clapboard house than they were in their cave. The voice of an ancient forebear rises within me and issues a warning cry. The cougar still lurks on the ledge over my head; the barbarian horde still threatens my town. I put my trust in the electronic appliances of my age; surely they will defend me against the pestilence that rises without warning and spreads like locusts across the land. But once again I know I am allowing myself to be deceived. The only security I know, that I will ever know, lies in me. And so I sit high on the windward deck and tell myself to

...more

I learned the interior life was as rewarding as the exterior life and that my richest moments occurred when I was absolutely still.

As I grew older and more experienced, I realized that the ability to distinguish between real and apparent dangers is fundamental to good judgment, and people who don’t possess it are seriously handicapped. They dwell in a state of incipient catastrophe, thinking only of what can go wrong and trying to ward it off before it occurs. They aren’t masters of reality, although they like to think they are; they’re masters of unreality because they let their fears, which are figments of an untrustworthy imagination, govern their lives. It’s as if they never break through a secret barrier that

...more

the world can’t be controlled; it’s patently not controllable—that’s the only physical principle I know for sure.

we have become so busy preventing the future that there’s never a now.

For the truth is that I already know as much about my fate as I need to know. The day will come when I will die. So the only matter of consequence before me is what I will do with my allotted time. I can remain on shore, paralyzed with fear, or I can raise my sails and dip and soar in the breeze.

Putting a boat in a house made as much sense to me as putting a sweater on a dog.

I believe he still carries his father’s voice around in his head and hears it wherever he goes. I believe he doesn’t do what he wants to do but what he thinks his father would like him to do, and so the never-ending quest for parental approval continues to govern his behavior, as if his father were watching his every move from the grave.

I know fathers are supposed to let go of sons, mothers of daughters, but I also know that it rarely happens that way. Parents cling to their children beyond all enduring, as if they have an absolute right to control their lives from the day they’re born. And so the onus passes from generation to generation until a child appears with the innate power to break the bind. That is the way of all flesh.

If my son were present, he would have done exactly what I would have done at the same age: fidgeted in his seat, rolled his eyes, and hoped that the lecture wouldn’t last too long. He needed someone to teach him to sail, but as much as I wanted to be his mentor I knew it couldn’t be me.

As a youth, I had regarded the loss of my parents as the central tragedy of my life. But as I grew older, I began to see that I had certain advantages over my friends, who had no choice except to model themselves after the parents they had. For a few that worked out, but for most it didn’t, and many had to rebel before they could discover who they were. But I had no such impediment in my way. I could choose my models wherever I found them, and I found them everywhere. I didn’t have to limit myself to one father and one mother; I could pick and reject as many as I wanted as I went along—and

...more

These men were my masters—and I had chosen them; they hadn’t chosen me. They didn’t impose themselves by offering gratuitous advice. If they saw a novice floundering in the wind, they didn’t rush up and tell him how to trim his sails. But if that same novice approached them later on and sought their counsel, neither did they turn their backs.

We don’t need critics to impress us with their knowledge, and we don’t need lecturers to talk to us as if we weren’t there. We don’t need people who hector us, badger us, teach us by rote, for they teach nothing at all.

By then I had enough sense to give him my blessing and get out of his way.

For a long time I thought those two events—the sinking of my boat and the birth of my son—were mere coincidence, but I no longer believe that’s so. In fact, I’m not sure I believe in coincidence at all. When two seemingly unrelated events occur simultaneously, we at least owe it to ourselves to question why. One phase of my life was coming to a close and another was about to begin. That much should have been clear.

But there is one thing about a checkbook; it doesn’t lie.

There’s an aspect to materialism that has to do with possession for its own sake, as if the goods we own are a measure of who we are. But there’s another aspect that has to do with attachment to objects themselves long after they have ceased to serve their original purpose in our lives. I

It’s a sad predicament, and yet I can understand how difficult it is to break the bond with those physical things that tie us to our past. I was wedded to my sloop; she was a part of me, but circumstances had transformed her from an asset into an encumbrance.

I had lived through a cycle of learning and caring, and having learned and cared I had to shed the past so I could begin the cycle over again.

They don’t know what they say. When I sit alone in my room or walk by myself by the edge of the sea, I summon up those I wish to be with from my memory. Some are alive and some are dead and some sprang full-blown from the genius of authors, and they are all real to me.

I spoke of the past, of what I remembered and what I missed and how I had come to terms as a man with the loss I had suffered as a boy. He stiffened, expressing surprise that I was “still struggling” with matters that had happened so long ago. I told him I wasn’t struggling with them; I was savoring them. “The desire to forget the past,” I said, “is a form of suicide.”

I think most of us are afraid that if we let ourselves feel our sorrow for the passing of the life that was, we will never regain our composure again. But the fear is misplaced; what should truly frighten us is the possibility that we might lose the power to recall the life we lived, which gives us our connection to ourselves. Our most terrifying diseases aren’t the ones that take our life; they’re the ones that cast us adrift on an empty sea by depriving us of our memories.