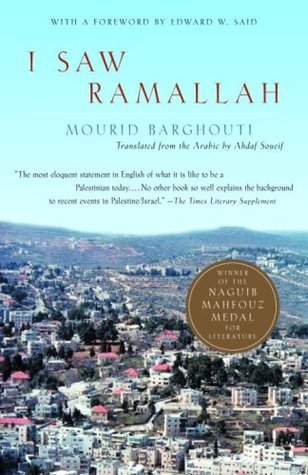

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Major figures of cultural importance like the assassinated novelist Ghassan Kanafani and the cartoonist Naji al-‘Ali haunt the book as well, reminders that no matter how gifted and artistically endowed Palestinians are, they are still subject to sudden death and unexplained disappearance.

And the world finds a name for us. They called us naziheen, the displaced ones. Displacement is like death. One thinks it happens only to other people.

He is despised for being a stranger, or sympathized with for being a stranger. The second is harder to bear than the first.

It is a land, like any land. We sing for it only so that we may remember the humiliation of having had it taken from us. Our song is not for some sacred thing of the past but for our current self-respect that is violated anew every day by the Occupation.

People like direct poetry only in times of injustice, times of communal silence. Times when they are unable to speak or to act. Poetry that whispers and suggests can only be felt by free men.

Khalid, son of the martyr Naji al-'Ali. Fayiz, son of the martyr Ghassan Kanafani. Hani, son of the martyr Wadi’ Haddad.

In the Caravan Hotel I got to know my brothers and my parents all over again. For everyone there were new and exceptional circumstances I could not know completely.

we can not ever fathom the pain and heartbreak that the Palestinians face. im breaking from within, knowing there are countless upon countless of families broken in this way.

A killer can strangle you with a silk scarf, or can smash your head in with an axe; in both cases you are dead.

Living people grow old but martyrs grow younger.

A tiresome friend is full of reproaches, full of blame, wanting an explanation for the inexplicable, wanting to understand everything. If he forgives you for a mistake he makes you feel he's forgiven you for a mistake. We do not choose our families but we do choose our friends, so, in my view, a tiresome friendship is a voluntary stupidity.

They speak of politics as ‘facts.’ As though no one had explained to them the difference between ‘facts’ and that ‘reality’ which includes all the emotions of people and their positions.

Politics is the family at breakfast. Who is there and who is absent and why. Who misses whom when the coffee is poured into the waiting cups. Can you, for example, afford your breakfast? Where are your children who have gone forever from these their usual chairs? Whom do you long for this morning?

How did the flower merchants make their millions and build their fine houses from selling the bouquets carried by mothers and sisters to the graveyards that are always damp: raindrops, flowers, and tears.

Occupation prevents you from managing your affairs in your own way. It interferes in every aspect of life and of death; it interferes with longing and anger and desire and walking in the street. It interferes with going anywhere and coming back, with going to market, the emergency hospital, the beach, the bedroom, or a distant capital.

Is it not odd that when we arrive at a new place living its new moment we start to look for our old things in it?

Husbands, sons, and daughters have been distributed among graves and detention camps, jobs and parties and factions of the Resistance, the lists of martyrs, the universities, the sources of livelihood in countries near and far.

They snatch you from your place suddenly, in a second. But you return very slowly. You watch yourself returning in silence. Always in silence. Your times in the faraway places watch too; they are curious: what will the stranger do with the reclaimed place and what will the place do with the returned stranger?

Say you are romantic. Time will coldly discipline you. Time makes us reel with realism.

Nothing that is absent ever comes back complete. Nothing is recaptured as it was.

that the most important value in life is knowledge and that it deserves every sacrifice.

She could not bear for one of us to be away from her, and the sad thing is that we all went away and stayed away for a long time. As for the best of us, the most precious of us, he left never to come back, and she had to bear it.

In fact, our hatred of the Occupation is essentially because it arrests the growth of our cities, of our societies, of our lives. It hinders their natural development.

He has the amazing contradictions of life, because he is a living creature before being the son of the eight o'clock news.

The details of the lives of all whom we love, the fluctuations of their fortunes in this world, all began with the ringing of the phone. A ring for joy, a ring for sorrow, a ring for yearning.

the displaced person can never be protected from the terrorism of the telephone.

He draws close when he is far away and feels distant when he is near.

The homeland does not leave the body until the last moment, the moment of death.

The telephone never stops ringing in the night of far-off countries.

Our calendars are broken, overlaid with pain, with bitter jokes and the smell of extinction.

It is easy to blur the truth with a simple linguistic trick: start your story from “Secondly.”

Start your story with “Secondly,” and the arrows of the Red Indians are the original criminals and the guns of the white men are entirely the victim. It is enough to start with “Secondly,” for the anger of the black man against the white to be barbarous. Start with “Secondly,” and Gandhi becomes responsible for the tragedies of the British. You only need to start your story with “Secondly,” and the burned Vietnamese will have wounded the humanity of the napalm, and Victor Jara's songs will be the shameful thing and not Pinochet's bullets, which killed so many thousands in the Santiago stadium.

...more