More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

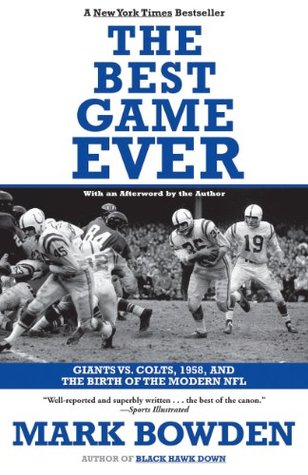

It was the greatest concentration of football talent ever assembled for a single game. On the field and roaming the sidelines, including Giants owners Wellington and Jack Mara, were seventeen future members of the NFL Hall of Fame.

Just over the horizon was a decade of restless social, political, and cultural upheaval, but none of that was obvious yet. Americans had never been more affluent, and had never had more leisure. And pro football, which was about to catch hold, would just shoulder on through all this coming change, growing ever more popular and ever more rich.

Television was perfect for action, particularly the suspense of live action. That’s how it had struck Orrin E. Dunlap Jr. of the New York Times after the first-ever televised game in 1939, a college matchup between Fordham University and Waynesburg College.

The idea of splitting a player out to one side to concentrate exclusively on running pass routes was relatively new. It had only been nine years since Los Angeles Rams coach Clark Shaughnessy, one of the game’s greatest innovators, had created the position by placing Elroy “Crazy Legs” Hirsch seven yards wide of the line of scrimmage.

arm. To better accommodate the pass, the dimensions of the ball were changed in 1934.

The upstart All-American Football Conference adopted free substitution when it was formed in 1946, and began playing games with separate offensive and defensive squads.

When that league merged with the NFL in 1950, free substitution was also adopted, all but ending the age of the two-way player. There were still a few athletes remarkable enough to play both ways—the last was the Eagles Chuck Bednarik, who played both center and linebacker until retiring in 1962—but the fifties ushered in pro football’s age of the specialist.

No one quarreled with Raymond’s results. He got better every year. He caught fifty-six passes in 1958, which led the league. He was so careful and deliberate about the way he caught and handled the ball that he would fumble only once in his thirteen-year career, perhaps the most remarkable and telling of all his lifetime stats.

Landry and Lombardi, on the other hand, were from the new, Paul Brown school of coaching. Like Weeb, they relished toughness and the controlled violence of the game, but they were also devotees of organization and careful preparation. Landry in particular was a film-study buff who approached coaching not as a job, but as a vocation. The year before Howell, Lombardi, and Landry took over, the Giants went three and nine. It took them just three seasons to reverse those numbers and win the NFL championship.

Someone in the crowd milling behind the end zone had kicked the network’s cable and unplugged America.