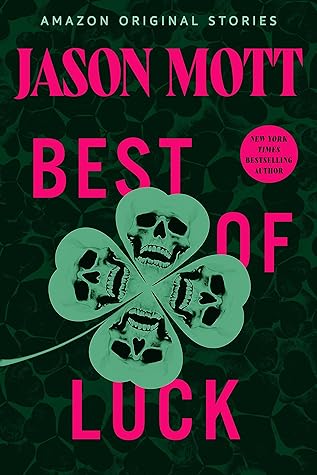

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“A good joke is just a small story, you know. Only difference is the delivery.” “I guess.”

“‘God damnit!’ Our Farmer yells. ‘My shovel?! My granddaddy made that shovel! Carved it hisself and give it to me. Been using that shovel for almost my whole damned life. I’m gone one week and you break it?’ “‘That’s about the size of it,’ the Neighbor says.

And for the first time since Barry woke up and found his best friend holding a shotgun on him, for the first time since his best friend told him he had come to kill him, Barry Whitmore laughed. He and Will both did. But like most things in life—even though it was wonderful and glimmering—it wouldn’t last.

As Barry took in the sickly image of his friend, Will heaved all of a sudden. He covered his mouth like he was fighting off vomiting and made an awful, guttural sound. That brought out the smell again. That smell.

It was a sour yet sweet smell. Old milk with a hint of cedar. Curdled Christmas. It was earthy and horrible . . . and it was the smell of rot. Of something living and dying at the same time.

“That’s right,” Will said. Then, without warning, his body clenched and he leaned forward and vomited blood onto the floor in front of him, drops and flecks of it splattering the very painting he was admiring. The sound of his vomiting was otherworldly. Like some horrible creature off in the distance of an unknown and haunted land.

“Jesus, Will. Who the fuck is Henry?” Will began to unbutton his shirt. He grimaced a little, looking anxious as each button came undone. “I’ll reintroduce you,” Will said. And then, both slowly and somehow suddenly, his shirt was open and Barry finally saw Henry. Now it was his turn to vomit. Barry barely made it to the sink in time.

Then there was that sound again: wind and air and mouths. A shiver ran down Barry’s spine. He thought he heard words.

He laughed then. It was a dark, ominous laugh. “What’s so funny?” Barry asked.

“So you’re going to kill me because the voice inside your head—inside your stomach—told you to kill me?” Barry asked. “That’s about the size of it,” Will said.

“I’m not going to admit to something I didn’t do. If you’re going to come into my house and kill me, if you’re going to be that kind of a monster, then I’m going to make you go all the way. I’m going to make you be the monster.” And then the long moment came. It was a moment that stretched back across decades of life and laughter and friendship.

Will’s hands finally uncurled from his stomach. Of their own accord, his hands made their way up to his mouth. His right hand opened his mouth by the upper jaw and his left hand grabbed his lower jaw. And then the two hands began pulling.

By now Will’s jaw had fully separated from his mouth. Blood flowed out and covered the table, and the tendrils—hairy and searching—came forth from his gaping maw and covered his face, pushing against him, bringing Henry—or whatever the thing was—out of Will’s body.

“Just bad luck,” Barry said. “That’s all. Nothing malicious. Just . . . just bad luck, Will. I’m sorry.”