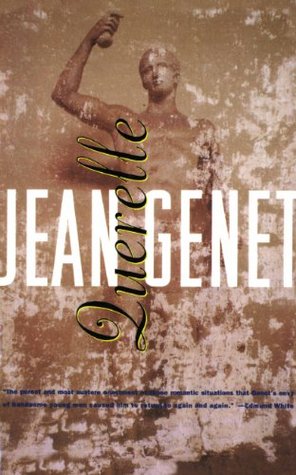

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

The man who dons a sailor’s outfit does not do so out of prudence only. His disguise relieves him from the necessity of going through all the rigamarole required in the execution of any preconceived murder. Thus we could say that the outfit does the following things for the criminal: it envelops him in clouds; it gives him the appearance of having come from that far-off line of the horizon where sea touches sky; with long, undulating and muscular strides he can walk across the waters, personifying the Great Bear, the Pole Star or the Southern Cross; it (we are still discussing this particular

...more

We ourselves have witnessed scenes of seduction. In that very long sentence beginning “it envelops him in clouds . . . ,” we did indulge in facile poeticisms, each one of the propositions being merely an argument in favor of the author’s personal proclivities.

The notion of love or lust appears as a natural corollary to the notion of Sea and Murder–and it is, moreover, the notion of love against nature.

That severe, at times almost suspicious look, a look that seems to pass judgment, with which the pederast appraises every young man he encounters, is really a brief, but intense meditation on his own loneliness.

Querelle was not used to the idea, one that had never really been formulated, that he was a monster.

He had only to give the slightest turn of the head, to left or right, to feel his cheek rub against the stiff, upturned collar of his peacoat. This contact reassured him. By it, he knew himself to be clothed, marvelously clothed.

Querelle pulled off one of his socks. Apart from the material benefits derived from his murders, Querelle was enriched by them in other ways. They deposited in him a kind of slimy sediment, and the stench it gave off served to deepen his despair.

They pulled apart, quickly. Suddenly they heard the sea. From the very beginning of this scene they had been close to the water’s edge. For a moment both of them felt frightened at the thought of having been so close to danger. Gil took out a cigarette and lit it. Roger saw the beauty of his face that looked as if it had been picked, like a flower, by those large hands, thick and covered with powdery dust, their palms illuminated now by a delicate and trembling flame.

He was a well-built man, wide-shouldered, but he felt within himself the presence of his own femininity, sometimes contained in a chickadee’s egg, the size of a pale blue or pink sugared almond, but sometimes brimming over to flood his entire body with its milk.

The Lieutenant knew to his great chagrin that this core of femininity could erupt in an instant and manifest itself in his face, his eyes, his fingertips, and mark every gesture of his by rendering it too gentle.

“He” wears those stains with a glorious impudence: they are his medals.

the door symbolized the cruelty that attends the rites of love. If the door was designed for protection, it had to be guarding a treasure such as only insensate dragons or invisible genies could hope to gain without being impaled to bleed on those spikes–unless, of course, it did open all by itself, to a word, a gesture from you, docker or soldier, for this night the most fortunate and blameless prince who may inherit the forbidden domains by power of magic.

For Madame Lysiane the door had other virtues. When closed, it transformed her, the lady of the house, into an oceanic pearl contained in the nacre of an oyster that was able to open its valve. and to close it. at will.

“Go.” Only this word the Lieutenant pronounced with regret, without that customary harshness,

his feelings had been soiled by shame, by a kind of nauseating vapor that threatened to mingle with all his thoughts in order to corrupt and decompose them.

When we see life, we call it beautiful. When we see death, we call it ugly. But it is more beautiful still to see one self living at great speed, right up to the moment of death.

Desolation appears greater when pinpointed by light.

He was doing it with despair in his soul, yet with an unexpressed inner certitude that this execution was necessary for him to go on living. Into what would he be transformed? A fairy.

He was holding Querelle with seemingly the same passion a female animal shows when holding the dead body of her young offspring–the attitude by which we comprehend what love is: consciousness of the division of what previously was one, of what it is to be thus divided, while you yourself are watching yourself.

A man whom you have killed is more alive than the living.

Uncomprehending, she looked at her lover talking to her from the bottom of the ocean.

“He’s afraid of getting poisoned by my mouth. It’s he who spurts venom, and it’s me who poisons him.”