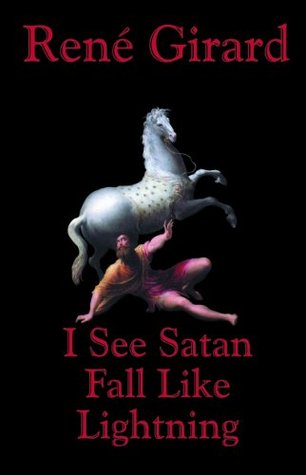

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Girard's anthropology focuses first on desire and its consequences. He calls it “mimetic desire” or “mimesis.” It's a desire that comes into being through imitation of others. These others we imitate Girard calls “models,” models of desire. He has also used the word “mediators,” because they are “go-betweens,” acting as agents between the individual imitating them and the world. There are various words in ordinary language that suggest what Girard is getting at: for example, “heroes” and “role models.” Even fashion models who “model” clothes are acting in this way for their public in the

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

He acutely perceived that it was associated with democracy, a political form he held in contempt. This absolute value—concern for the victim—was already becoming secularized, torn from its religious and theological moorings, in Nietzsche's time.

The concern for victims has become such an absolute value that not only do those Nietzsche influenced not attack it, but it has become the unspoken dogma of “political correctness” and “victimism.” Political correctness surrounds most of our public institutions, including above all colleges and universities, with an aura that prohibits using any word or allowing any discussion that might offend some minority group or victim or potential victim. It tends to stifle public discussion and debate of ideas and issues.

Both political correctness and victimism stem from an authentic reality from the standpoint of the Christian faith. That reality is God's revelation through Jesus Christ of the victim mechanism and the way into God's new community of love and nonviolence. But Satan has a tremendous ability to adapt to what God does and to imitate God, and so Satan—the ancient and tremendous power of the victim mechanism that expels violence through violence—is able to disguise himself and pose even as concern for victims.

What Jesus invites us to imitate is his own desire, the spirit that directs him toward the goal on which his intention is fixed: to resemble God the Father as much as possible.

Why does Jesus regard the Father and himself as the best model for all humans? Because neither the Father nor the Son desires greedily, egotistically. God “makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and he sends his rain on the just and on the unjust.” God gives to us without counting, without marking the least difference between us. He lets the weeds grow with the wheat until the time of harvest. If we imitate the detached generosity of God, then the trap of mimetic rivalries will never close over us. This is why Jesus says also, “Ask, and it will be given to you….”

When Jesus declares that he does not abolish the Law but fulfills it, he articulates a logical consequence of his teaching. The goal of the Law is peace among humankind. Jesus never scorns the Law, even when it takes the form of prohibitions. Unlike modern thinkers, he knows quite well that to avoid conflicts, it is necessary to begin with prohibitions.

Resorting to a psychological explanation is less innocent than it appears. In refusing the mimetic interpretation, in looking for the failure of Peter in purely individual causes, we attempt to demonstrate, unconsciously of course, that in Peter's place we would have responded differently; we would not have denied Jesus.

The children repeat the crimes of their fathers precisely because they believe they are morally superior to them. This false difference is already the mimetic illusion of modern individualism, which represents the greatest resistance to the mimetic truth that is reenacted again and again in human relations. The paradox is that the resistance itself brings about the reenactment.

The more one is crucified, the more one burns to participate in the crucifixion of someone more crucified than oneself.

For the contagion that divides, fragments, and decomposes communities is substituted a collective contagion that gathers all those scandalized to act against a single victim who is promoted to the role of universal scandal.

This wisdom says that the principalities and powers nailed Christ to the Cross and stripped him of everything without any damage at all to themselves, without endangering themselves. Our text thus boldly contradicts everything so-called common sense regards as the hard and sad truth about the Passion. The powers are not invisible; they are dazzling presences in our world. They hold the first rank. They never stop strutting and flaunting their power and riches. There's no need to make an exhibition of them: they put themselves on permanent exhibition.

Starting from Paul's statement that I have just quoted, Origen and many of the Greek Fathers elaborated a thesis that played a great role as the first centuries of Christianity unfolded, that of Satan duped by the Cross.4 Satan means the same in this formulation as those St. Paul names as the “princes of this world.” In Western Christianity this thesis has not met with the same favor as in the East, and finally, as far as I know, it disappeared.

The thesis interprets the Cross as a kind of divine trap, a ruse of God that is even stronger and cleverer than Satan's ruses. Certain Fathers amplified this idea into a strange metaphor that contributed to the distrust in the West. Christ is compared to the bait the fisher puts on the hook to catch a hungry fish, and that fish is Satan.

Medieval and modern theories of redemption all look in the direction of God for the causes of the Crucifixion: God's honor, God's justice, even God's anger, must be satisfied. These theories don't succeed because they don't seriously look in the direction where the answer must lie: sinful humanity, human relations, mimetic contagion, which is the same thing as Satan. They speak much of original sin, but they fail to make the idea concrete. That is why they give an impression of being arbitrary and unjust to human beings, even if they are theologically sound.

THE PASSION ACCOUNTS shed a light on mimetic contagion that deprives the victim mechanism of what it needs to be truly unanimous and to generate the systems of myth and ritual: the participants’ unawareness of what is driving them.

This knowledge, which Paul says comes from the Cross, is not esoteric at all. To grasp it, we need only ascertain that we all now observe and understand situations of oppression and persecution that earlier societies did not detect or took to be inevitable.

This dynamic concept of Satan enables the Gospels to articulate the founding paradox of archaic societies. They exist only by virtue of the sickness that should prevent their existence. In its acute crises the sickness of desire generates its own antidote, the violent and pacifying unanimity of the scapegoat. The pacifying effects of this violence continue in the ritual systems that stabilize human communities. All of this is epitomized in the statement “Satan expels Satan.” The Gospel theory of Satan uncovers a secret that neither ancient nor modern anthropologies have ever discovered.

...more

We don't detect the mimetic snowballing because we participate in it without realizing it. In this case we are condemned to a lie we can never rectify, for we believe sincerely in the guilt of our scapegoats. This is what myths do. 2.We detect the mimetic snowballing in which we do not participate, and then we can describe it as it actually is. We restore the scapegoats unjustly condemned. Only the Bible and the Gospels are capable of this.

The Resurrection empowers Peter and Paul, as well as all believers after them, to understand that all imprisonment in sacred violence is violence done to Christ. Humankind is never the victim of God; God is always the victim of humankind.