More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

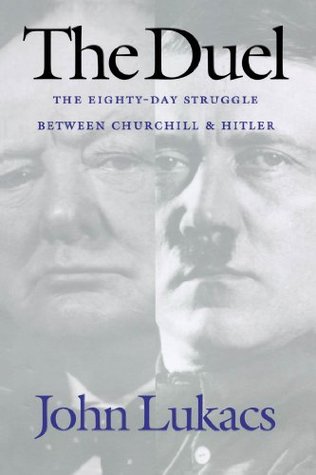

John Lukacs

Read between

November 7 - November 17, 2021

Napoleon once said that in war, as in prostitution, amateurs are often better than professionals. Hitler may have been an amateur at generalship, but he possessed the great professional talent applicable to all human affairs: an understanding of human nature and the understanding of the weaknesses of his opponents. That was enough to carry him very far.

IN THE gloomy year 1948 Churchill wrote about 1940. The war had been won but the peace was lost.

Had Churchill known what Hitler revealed to his generals on 31 July he would have had yet another reason to be confident: for on that day Hitler said that he would invade Russia probably before England.

The italicized passages were underlined by Haider. He was obviously impressed with Hitler’s reasoning. We are less inclined to that. But only for one reason. We know what happened to the German army in Russia; we know that, after having invaded Russia, Hitler lost the war. Yet in Russia, in 1941, he came very close to winning it. And what would have happened then? There was more to his reasoning than megalomania. Nor was it a return to the main objective of his life that he had set forth in Mein Kampf, the winning of the European east for the German people and their Reich.

Churchill, as Hitler thought, had two hopes: America and Russia. Against America he could do nothing. But with Russian power destroyed, his continental power would be unbeatable. Then Churchill, and Roosevelt, could do nothing to defeat him.

Churchill did not know what took place at the Berghof on 31 July. But he had suspected something like that for some time. As early as 27 June he wrote to Smuts: “If Hitler fails to beat us here he will probably recoil eastward. Indeed he may do this even without trying invasion.”

Roosevelt and Hitler were of course very different men. Both were secretive, but in different ways. Hitler kept some of his most important beliefs to himself, while he was a master at convincing people to believe what he wanted them to believe. Roosevelt’s ideas were less complicated than Hitler’s; but it was his custom to prepare his decisions surreptitiously, denying them in the face of truth, if need be; he was a master of dissimulation. His acts and words were always dependent on his calculations of domestic politics — that is, of his potential internal opposition.