More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 11 - December 28, 2016

The Japanese affix the suffix "do" to the names of the Zen arts. "Do" is an important word in Zen. It is the Japanese translation of the Chinese word, "Tao." It has no direct equivalent in English, perhaps because there is no analogous concept in Western culture. "Do" is usually translated as "Way" and connotes path or road to spiritual awakening. The Zen arts can be referred to as "Ways" and are not limited to the martial arts: kyudo is the Way of the bow; kendo is the Way of the sword; karate-do is the Way of the empty fist; shodo is the Way of writing ("spiritual" calligraphy); and chado is

...more

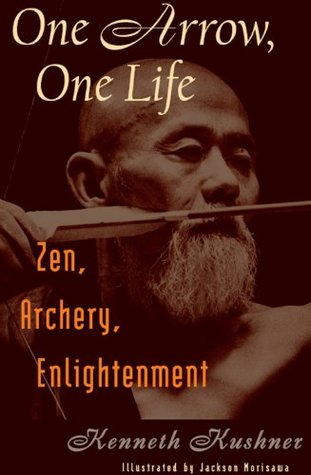

First, for those interested in learning more about kyudo, I recommend the book Zen Kyudo by my teacher, Jackson Morisawa.

Samadhi: Self Development in Zen, Swordsmanship, and Psychotherapy, by Mike Sayama,5 which has translations of instructions

Thousands of repetitions and out of one's true self perfection emerges.

Zen Saying

"Thousands of repetitions and out of one's true self perfection emerges."

Ri can best be understood as universal truths or as the underlying principles of the Universe.

Ri is formless and unchanging. Ri is ineffable; it is impossible to describe adequately underlying principles in words. Because principles have no form, the way they manifest themselves will vary from situation to situation. Specific manifestations of ri also are referred to as ji. Thus, in the Ways, techniques are seen as specific manifestations of the underlying principles. Ji is an embodiment of ri in specific situations, but is not itself ri in the same sense that a specific recipe is not in itself the underlying principles of cooking.

There are means of forcing the situation a little to bring off a favorite trick. This is skillful ji, but it cannot be said to be ri.2

In the Ways, ji connotes skill and ri connotes inspiration. When one sees into the underlying principles, one's performance becomes inspired.

When one moves, kneels, and bows in the ceremony before and after the shot, a secure, balanced base is maintained; the pelvis is thrust forward, and the spine remains in its natural position.

In discussing Issha Zetsumei, Mr. Morisawa writes, "Each arrow is final and decisive as each moment is the ultimate."

In Zen, it is recognized that there are

no second chances in life; one strives to pay full attention to each instant, to every activity no matter how trivial it might seem. One should throw oneself fully into all activities. Each activity should be done as if it were one's only activity on Earth. In kyudo this means to concentrate on every arrow as if it were the only arrow that the kyudoka will ever shoot.

Samadhi and mushin are often used more or less interchangeably.

Tanouye Roshi likens mushin to being able to see through one's thoughts as one looks through a propeller. One's experience is pure, unclouded by delusive thought. Consciousness is then free flowing; it moves from object to object, from event to event without being stopped by delusive thoughts.

When one is in the right frame of mind, one's peripheral vision is actually quite large; one has panoramic vision.

mere knowledge or awareness of the precise moment to release the arrow in the cycle of oscillations in aiming is not adequate. One must have that knowledge and release the arrow at that same moment. In mushin one acts in the naturally correct way; that is, in accord with the underlying principles. To be able to act in accord with underlying principles, one must lose the sense that one is planning or creating one's actions.

There is a Japanese phrase, "ma o shimeru,"

which means "to eliminate the space in between." Jackson Morisawa writes about this phrase as follows: When the operation of the mind and the body coincide with one point in time and when the space between thought and conduct is eliminated in such a way that they are in perfect unison, we may regard such a moment as the present.1

In Japanese art, the image of the moon reflecting on the water is common. I understand this to symbolize ma o shimeru. Just as the moon instantly hits the water, so should our thoughts and actions be united.

The proper release is often likened to snow building up and suddenly slipping off a bamboo leaf.

Mushin, not technique, solves the paradox of the release. Mushin allows one to transcend technique and intuit the naturally correct way of letting the string release itself from the hand. In this way, the release is neither purposeful nor purposeless.

At kai, there are two major lines of force in the body. A vertical line is formed by the downward pressure of the breath and the raising of the spine. Simultaneously, a horizontal line of force is formed by the expansion of the chest and the outward pressure of the legs. As he holds the arrow at kai, the kyudoka concentrates on adjusting his breathing and posture so the vertical and horizontal lines of force meet at right angles.

having Zen understanding only when sitting cross-legged or when shooting an arrow is not adequate. To have the same understanding when one is engaged in everyday activities is what is really important, for all activities are part of that same whole. Thus, picking a weed as naturally as snow falls off a bamboo leaf is an expression of the Zen awareness. Seeing a weed and being able simply to pick it without "any space in between" is in itself a koan of profound significance. CHAPTER 5 The Naturally Correct Way You have to learn how to push the rock where it wants to go.

"Like a heavy drop of water that decides to be free, the arrow liberates itself."

In Zen, students strive to accord with ri in everything that they do. This is true whether they are moving rocks, preparing dinner, picking weeds, hauling garbage to the dump or washing dishes. In every activity, one tries to find the invisible creases.

We study the Zen arts to learn their principles and how to apply them to all spheres of life. There is, however, a certain seductiveness to the arts; it is easy to lose the larger perspective and treat the arts as ends in themselves.

The downward pressure of the breath and the extension of the spine cause his chest to expand.

There is another, more profound, level to zanshin: continuity of spirit outside the kyudo dojo. In this regard, Jackson Morisawa writes: "The remaining heart also means that one must carry over the kyudo principles into one's daily life."2

"The pain isn't getting worse, your tolerance of it is getting less."

Instead of waiting for a miracle to happen that would enable me to sit painlessly, I realized I had to focus on learning to live with the pain.

Zen training is a constant struggle against the ego, which is the seat of thoughts and emotions that cloud our awareness. These thoughts and feelings, referred to collectively as delusions, are often compared to demons. They swarm over us and seduce us into pursuing them. Over the course of training, one becomes aware of how pervasive such delusions are and how difficult it is to break the grip they have over us.

To cut through the waves of delusional thoughts that cloud our perception, to destroy the ego; that is the true target in kyudo. This is shown in an old poem: No target's erected No bow's drawn And the arrow leaves the string: It may not hit, But it does not miss.2

In kyudo, we must look inward and face our inner enemies. As one progresses in kyudo, one gains increasing insight into one's psychological makeup. This is a painful process, for we must acknowledge flaws in our character that make us miss our mark. Greed, competitiveness, vanity, self-criticism, shyness, fear, need for approval are but a few of the personality characteristics that can lead to delusive thoughts that cloud our awareness in kyudo.

The Dojo is literally the battlefield of life, a "field of life and death." The only difference between it and the battlefield of war is that in the Dojo the trainee may die many times over and live to count these deaths as experiences which benefit his development in the ways and eventually to be able to transcend life and death."5

The kyudo student endeavors to take life's difficulties in stride. To face hardships and disappointments with the calm that one has when one misses the target; to have the same composure in the face of calamity that the master has when his string breaks at full draw; to accept full responsibility for one's mistakes and to try again; that is true zanshin. The student who strives to live his life that way understands that the true target in kyudo is not the piece of paper that is ninety feet away; the true target is within.

is also the driving force behind consciousness and, for that reason, is often described as "psychophysical energy."