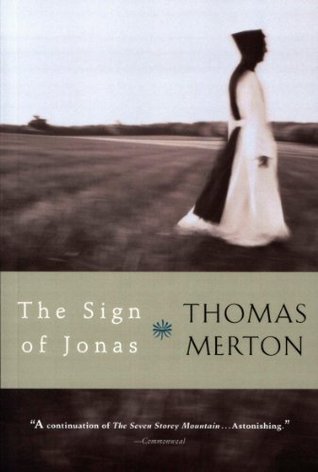

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

I had a pious thought, but I am not going to write it down.

To discover the Trinity is to discover a deeper solitude. The love of the Three Divine Persons holds your heart in its strength and builds about you a wall of quiet that the noise of exterior things can only penetrate with difficulty. You no longer have to strive to resist the world or escape it: material things affect you little. And thus you use and possess them as you should, for you dominate them, in making them serve the ends of prayer and charity, instead of letting them dominate you with the tyranny of your own selfishness and cupidity.

And so it is not sufficient to rush into church with a desire for contemplation or to do a lot of good works and acts of virtue with a desire for sanctity. In all the aspects of life the supreme good which includes everything else is God’s will.

God never does things by halves. He does not sanctify us patch upon patch. He does not make us priests or make us saints by superimposing an extraordinary existence upon our ordinary lives. He takes our whole life and our whole being and elevates it to a supernatural level, transforms it completely from within, and leaves it exteriorly what it is: ordinary.

The two most characteristic aspects of divine charity in the heart of a priest are gratitude and mercy. Gratitude is the mode of his charity for the Father, mercy is the expression of God’s charity, acting in him, reaching through him to his fellow men. Gratitude and mercy meet and blend perfectly in the Mass, which is nothing else but the charity of the Father for us, the charity of the Son for us and for the Father, the Charity of the Spirit Who is Charity uniting us to the Father in the Son.

It leaves one thinking that all things eventually turn out the way they ought to, even though it seems they might have been much better.

Nevertheless, in the depth of this abysmal testing and disintegration of my spirit, in December, 1950, I suddenly discovered completely new moral resources, a spring of new life, a peace and a happiness that I had never known before and which subsisted in the face of nameless, interior terror. In this journal, I have described the peace, not the terror: and I believe that I have done well, because as time went on, the peace grew and the terror vanished. It was the peace that was real, and the terror that was an illusion.

And now, for the first time, I began to know what it means to be alone. Before becoming a priest I had made a great fuss about solitude and had been rather a nuisance to my superiors and directors in my aspirations for a solitary life. Now, after my ordination, I discovered that the essence of a solitary vocation is that it is a vocation to fear, to helplessness, to isolation in the invisible God. Having found this, I now began for the first time in my life to taste a happiness that was so complete and so profound that I no longer needed to reflect upon it. There was no longer any need to

...more

Jesus did not die to prove any argument of ours.

The thing to do when you have made a mistake is not to give up doing what you were doing and start something altogether new, but to start over again with the thing you began badly and try, for the love of God, to do it well.

In the natural order, perhaps solitaries are made by severe mothers.

worrying about nothing but the will and the glory of God, finding these as best I can in the sacrament of the present moment.

I am sorry that I have not lived in them. Their words are full of the living waters of those true tears with which You taught the Samaritan your mercy. (She did not weep with her eyes—or if she did the Gospel does not tell us: but her simplicity and frankness were her compunction. Her penance was above all a matter of admiration: “I have found a man who told me everything I have ever done. Can He be the Christ?”)

The Pharisees accused the woman in adultery and when Jesus bent down to write with His finger in the dust, perhaps he meant to show them by this mystery, that the judgments of men are words written in the dust, and that only God’s judgments are true and just.

We too have all married over and over again, and yet we have no husband. But thank God for the hill, the sky, the morning sun, the manna on the ground which every morning renews our lives and makes us forever virgins.

Ecce nova facio omnia!*

Thus I stand on the threshold of a new existence. The one who is going to be most fully formed by the new scholasticate is the Master of the Scholastics. It is as if I were beginning all over again to be a Cistercian: but this time I am doing it without asking myself the abstract questions which are the luxury and the torment of one’s monastic adolescence.

What is my new desert? The name of it is compassion. There is no wilderness so terrible, so beautiful, so arid and so fruitful as the wilderness of compassion.

And there I have discovered that after all what the monks most need is not conferences on mysticism but more light about the ordinary virtues, whether they be faith or prudence, charity or temperance, hope or justice or fortitude.

Nevertheless, Your compassion singles out and separates the one on whom Your mercy falls, and sets him apart from the multitudes even though You leave him in the midst of the multitudes. . . .

*“He lived in the joy of God, and by the power of this good he was himself good.”