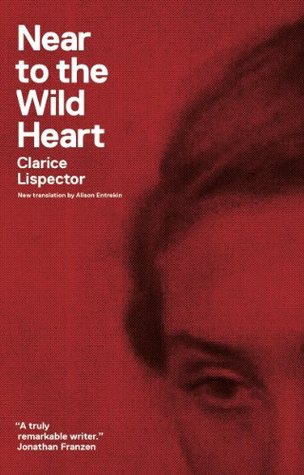

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“It isn’t hard, you just make it up as you go along.”

Between her and the objects there was something, but whenever she caught that something in her hand, like a fly, and then peeked at it—though she was careful not to let anything escape—she only found her own hand, rosy pink and disappointed.

if something hurt and if she watched the hands of the clock while it hurt, she’d see that the minutes counted on the clock passed and the hurt kept on hurting.

Or, even when nothing hurt, if she stood in front of the clock watching it, whatever she wasn’t feeling was also greater than the minutes counted on the clock.

The certainty that evil is my calling, thought Joana. What else was that feeling of contained force, ready to burst forth in violence, that longing to apply it with her eyes closed, all of it, with the rash confidence of a wild beast? Wasn’t it in evil alone that you could breathe fearlessly, accepting the air and your lungs? Not even pleasure would give me as much pleasure as evil, she thought surprised. She felt a perfect animal inside her, full of contradictions, of selfishness and vitality.

as if she had merely been interrupted by him,

goodness makes me want to be sick. Goodness was lukewarm and light. It smelled of raw meat kept for too long. Without entirely rotting in spite of everything. It was freshened up from time to time, seasoned a little, enough to keep it a piece of lukewarm, quiet meat.

nothing that I am not can interest me, it is impossible to be any more than what you are

It is curious that I can’t say who I am. That is to say, I know it all too well, but I can’t say it. More than anything, I’m afraid to say it, because the moment I try to speak not only do I fail to express what I feel but what I feel slowly becomes what I say.

Or at least what makes me act is not what I feel but what I say.

Pity is my way of loving. Of hating and communicating.

It is what sustains me against the world,

Tiredness slithering through her body, lucidity fleeing the octopus.

“I’d like to know: once you’re happy what happens? What comes next?” she repeated obstinately.

“Being happy is for what?”

Otávio made her into something that wasn’t her but himself and which Joana received out of pity for both, because both were incapable of freeing themselves through love, because she had meekly accepted her own fear of suffering, her inability to move beyond the frontier of revolt. Besides: how could she tie herself to a man without allowing him to imprison her? How could she prevent him from developing his four walls over her body and soul? And was there a way to have things without those things possessing her?

She felt like a dry branch, sticking out of the air. Brittle, covered in old bark. Maybe she was thirsty, but there was no water nearby.

And above all the suffocating certainty that if a man were to embrace her at that moment she would feel not a soft sweetness in her nerves, but lime juice stinging them, her body like wood near fire, warped, crackling, dry.