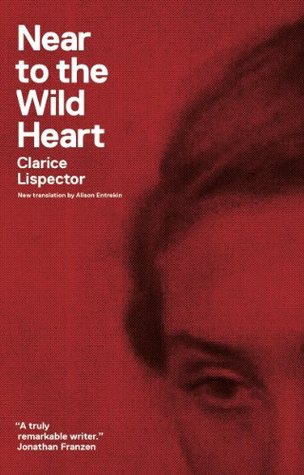

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“Clarice Lispector was a foreigner. . . . The foreignness of her prose is one of the most overwhelming facts of our literary history, and even of the history of our language.”

instead intimately connected to the sacred realms of sexuality and creation. A word does not describe a preexisting thing but actually is that thing, or a word that creates the thing it describes: the search for that mystic word, the “word that has its own light,” is the search of a lifetime.

A word does not describe a preexisting thing but actually is that thing, or a word that creates the thing it describes: the search for that mystic word, the “word that has its own light,” is the search of a lifetime.

“I was prepared, I don’t know why especially, for an acid beginning and a solitary end. Your words disarmed me. I suddenly even felt uneasy at being so well received. I who didn’t expect to be received at all. Besides, the repulsion of others—I thought—would make me harder, more bound to the path of the work I had chosen.

Another thing: if something hurt and if she watched the hands of the clock while it hurt, she’d see that the minutes counted on the clock passed and the hurt kept on hurting.

Everything was like the noise of the tram before falling asleep, until you felt a little afraid and drifted off.

The certainty that evil is my calling, thought Joana. What else was that feeling of contained force, ready to burst forth in violence, that longing to apply it with her eyes closed, all of it, with the rash confidence of a wild beast? Wasn’t it in evil alone that you could breathe fearlessly, accepting the air and your lungs? Not even pleasure would give me as much pleasure as evil, she thought surprised. She felt a perfect animal inside her, full of contradictions, of selfishness and vitality.

The minute she sensed he had left the house, however, she transformed, concentrated on herself and, as if she had merely been interrupted by him, continued slowly living the thread of her childhood, forgetting him and moving from room to room profoundly alone.

Yes, she felt a perfect animal inside her. The thought of one day setting this animal loose disgusted her. Perhaps for fear of lack of aesthetic. Or dreading a revelation

goodness makes me want to be sick. Goodness was lukewarm and light. It smelled of raw meat kept for too long. Without entirely rotting in spite of everything. It was freshened up from time to time, seasoned a little, enough to keep it a piece of lukewarm, quiet meat.

She was also moved when she read horrible novels in which evil was cold and intense like a tub full of ice. As if she were watching someone drink water only to discover her own thirst, profound and ancient. Maybe it was just a lack of life: she was living less than she could and imagined that her thirst required floods.

The taste of evil—chewing red, swallowing sugary fire.

Don’t accuse myself. Seek the basis of selfishness: nothing that I am not can interest me, it is impossible to be any more than what you are (nevertheless I exceed myself even when I’m not delirious, I am more than myself almost normally);

accept everything that comes from me because I am unaware of the causes and I may be trampling something vital without knowing it; this is my greatest humility,

It’s because I’m still very young and whenever I am touched or not touched, I feel—she reflected.

In the former, in the final center, the simple and adjectiveless feeling, blind as a rolling stone. In the imagination, for it alone has the power of evil, just the enlarged and transformed vision: beneath it the impassive truth. You lie and stumble into the truth. Even in her freedom, when she chose cheerful new paths, she later recognized them.

My consciousness strays, but it doesn’t matter, I find the greatest serenity in hallucination.

I feel who I am and the impression is lodged in the highest part of my brain, on my lips (especially on my tongue), on the surface of my arms and also running through me, deep inside my body, but where, exactly where, I can’t say.

But above all where does this certainty of being alive come from? No, I am not well. For no one asks themselves these questions and I . . . But all you have to do is be quiet in order to discern, beneath all the realities, the only irreducible one, that of existence.

Pity is my way of loving. Of hating and communicating. It is what sustains me against the world, just as one person lives through desire, another through fear.

Even by herself at a certain point in the game she lost the feeling that she was lying— and she was afraid of not being present in all of her thoughts. She wanted the sea and felt the sheets on the bed. The day went on and left her behind, alone.

I’d met her when I was twenty, fleetingly. And in a moment of distress, out of so many friends (and even you, as I didn’t know what had become of you), at that moment I thought of her.

To cheer herself up she thought: tomorrow, first thing tomorrow see the living chickens.

“I’d like to know: once you’re happy what happens? What comes next?” she repeated obstinately.

Joana received out of pity for both, because both were incapable of freeing themselves through love, because she had meekly accepted her own fear of suffering, her inability to move beyond the frontier of revolt. Besides: how could she tie herself to a man without allowing him to imprison her? How could she prevent him from developing his four walls over her body and soul? And was there a way to have things without those things possessing her?

She couldn’t fool herself because she knew she was also living and that those moments were the peak of something difficult, of a painful experience for which she should be thankful: almost as if she were feeling time outside herself, in a detached manner.

She breathed in the warm, clear afternoon air and the part of her that needed water was still tense and stiff like someone waiting blindfolded for a gunshot.

Inside her it was as if death didn’t exist, as if love could weld her, as if eternity were renewal.

The freedom she sometimes felt. It didn’t come from clear reflections, but a state that seemed to be made of perceptions too organic to be formulated as thoughts.

Eternity wasn’t just time, but something like the deeply rooted certainty that she couldn’t contain it in her body because of death; the impossibility of going beyond eternity was eternity; and a feeling in absolute, almost abstract purity was also eternal.

There were many good feelings. Climbing the hill, stopping at the top and, without looking, feeling the ground covered behind her, the farm in the distance. The wind ruffling her clothes, her hair. Her arms free, heart closing and opening wildly, but her face bright and serene under the sun. And knowing above all that the earth beneath her feet was so deep and so secret that she need not fear the invasion of understanding dissolving its mystery. This feeling had a quality of glory.

To have a vision, the thing didn’t have to be sad or happy or manifest itself. All it had to do was exist, preferably still and silent, in order to feel the mark in it. For heaven’s sake, the mark of existence

Her confusion didn’t just lend charm, however, but brought reality itself. It struck her that if she clearly ordered and explained what she had felt, she would have destroyed the essence of “everything is one.”

In her confusion, she was the truth itself unwittingly, which perhaps provided more power-of-life than knowing it. The truth which, although revealed, Joana couldn’t use because it wasn’t a part of her stem, but her root, binding her body to everything that was no longer hers, imponderable, impalpable.

Oh, there were many reasons for joy, joy without laughter, serious, profound, fresh. When she discovered things about herself at the precise moment in which she spok...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

“I don’t miss it, because I have my childhood more now than when it was happening . . .”

Even suffering was good because while the lowest suffering was taking place she also existed—like a separate river.

“Lord help me, when is there harm in it Joana?” “When you steal and are afraid. I’m neither happy nor sad.”

“Animal life boils down to this pursuit of pleasure after all. Human life is more complex: it boils down to the pursuit of pleasure, to fear of it, and above all to the dissatisfaction of the time in between.

All yearning is pursuit of pleasure. All remorse, pity, benevolence, is fear of it. All despair and seeking alternative routes are dissatisfaction. There you have it in a nutshell, if you wish. Do you understand?”

those who deny themselves . . . Because there are the . . . the plans, those made of soil which will never flourish without fertilizer.”

“Never suffer because you don’t have an opinion on this or that topic. Never suffer because you are not something or because you are.

What was going on? Everything was receding . . . And suddenly the setting stood out in her awareness with a scream, loomed up in all its detail submerging the people in a big wave . . . Her very feet were floating. The room where she had spent so many afternoons glittered in the crescendo of an orchestra, silently, avenging itself for her distraction.

From time to time, busy with their toys, they would glance at one another restlessly, as if to make sure they still existed. Then they resumed their lukewarm distance that was occasionally reduced by a cold or a birthday. They no doubt slept together thought Joana without pleasure in her malice.

At this moment my inspiration hurts all over my body. An instant more and it will need to be more than inspiration. And instead of this asphyxiating happiness, like too much air, I will clearly feel the impotence of having more than inspiration, of going beyond it, of possessing the thing itself—and really being a star. Where madness, madness leads.

I can hardly believe that I have limits, that I am cut out and defined. I feel scattered in the air, thinking inside other beings, living in things beyond myself.

But dreams are more complete than reality, which drowns me in the unconscious. What matters then: to live or to know you are living?—Very

will I still have something to live on? Or will everything I say fall short of or beyond life?—I try to push away everything that is a life form. I try to isolate myself in order to find life in itself.

In my interior I find the silence I seek. But in it I become so lost from any memory of a human being and of myself, that I make this impression into the certainty of physical solitude.

Freedom isn’t enough. What I desire doesn’t have a name yet.—I am thus a toy that is wound up and which when done will not find its own, deeper life. Try to calmly admit that I may only find it if I look for it in the small springs. Otherwise I will die of thirst.