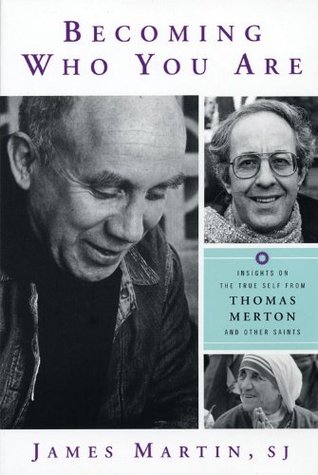

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

James Martin

Read between

March 29, 2019 - February 5, 2022

The Seven Storey Mountain, Merton wonders how much of his later life was owed to their example. He writes, “But one day I shall know, and it is good to be able to be confident that I will see them again and be able to thank them.”

While still a student at Cambridge, Tom fathered a child. It is a hazy incident that was concealed in some pious biographies of Merton, and, according to at least one source, was later removed from his autobiography by his religious superiors in the Trappist order.

He had also lost his scholarship at Cambridge due to a combination of bad grades, drinking and general carousing.

He also, gradually, became more interested in religion. Raised a desultory Christian, Merton found himself attracted to Catholicism through a variety of sources: through his intellect, through art, through his emotional life, and through the example of the few other Catholics he knew.

After his conversion to Catholicism, Tom’s life changed rapidly. He finished his master’s degree in English at Columbia and almost immediately began to consider becoming a priest. With

but was rejected,

Thus Merton’s life changed again, and he became, as he put it, ruefully, “the famous Thomas Merton.”

He questioned his monastic vocation as much as he embraced it. He desired solitude as much as he craved attention and affection from his brothers. He sought intimacy with others as much as he treasured his chastity. He battled with his religious superiors as much as he hoped to follow his vow of obedience. Most of all, he wished for fame and influence as much as he saw that humility was the foundation for a healthy monastic life.

“His whole life was a quest for freedom—the freedom to be open to the wonderful reality that God has made, to God himself, to what is!”

In 1965, Merton became a hermit on the grounds of the monastery. His little hermitage, at first a plain cinder-block building with a working fireplace but no bathroom, seems to have brought him greater peace—as well as some greater agitation as he struggled to live with himself.

Toward the end of his life, Merton, the monk who took a vow of stability, felt the desire to travel, but his abbot usually denied the requests.

All I have to offer is my own experience, my own reading of Thomas Merton, and what his writings on the true self have meant in my own spiritual life.

Merton said many times that when it comes to spirituality, experience is the place to start.

specifically The Seven Storey Mountain and No Man Is An Island that led me to where I am today and helped me become the person I was meant to be.

One day she accidentally ran over my rosary beads with the vacuum cleaner. When she pulled it out, it had lost three beads. When I came home from school I spied it on my bedpost and said, “Hey look what happened to my rosary beads!” Hoping to make me feel better, she said, “Well, look on the bright side. Now it won’t take you so long to pray it!”

I used to imagine God as the Great Problem Solver, the one who would fix everything if I just prayed hard enough, used the right prayers, and prayed in precisely the right way. God was powerful, I thought, but also distant. And if the Great Problem Solver couldn’t fix things, which seemed to occur more frequently than I would have liked, I turned to Saint Jude. I figured that if it was beyond the capacity of God to do something, then surely it must be a hopeless cause, and it was time to call on Saint Jude.

though I was by that point rather fond of Saint Jude, I was afraid of what my friends might say if they saw a strange plastic statue standing on my dresser. So Saint Jude was stuffed inside my sock drawer, and was brought out of the drawer only on special occasions.

So, when I entered the Jesuits, at age twenty-seven, I did so with only an eleven-year-old’s knowledge about the faith.

The only problem was that I couldn’t see a way out.

I got the idea that Merton was bright, funny, holy, and altogether unique. But there was something else about the show that drew me.

Here was a man, roughly my own age, who had struggled with the same things I did: pride, disappointment, confusion, doubt, sadness, loneliness.

“finally”

To paraphrase Merton in his book The Sign of Jonas, all of my training pointed one way, and all of my ideals the other.

There I was, “striving to be something I would never want to be.”

The Great Problem Solver, as it turned out, had been at work on a problem that I had only dimly comprehended.

“striving to be something that we would never want to be” continued to be part of my daily meditation.

Overall, the quest both to understand oneself and finally accept oneself was a key journey for me as a Jesuit novice.

“We cannot become ourselves unless we know ourselves.”

Before coming to know the true self, one must confront the false self that one has usually spent a lifetime constructing and nourishing.

Merton identifies the false self as the person that we wish to present to the world, and the person we want the whole world to revolve around:

And I wind experiences around myself and cover myself with pleasures and glory like bandages in order to make myself perceptible to myself and to the world, as if I were an invisible body that could only become visible when something visible covered its surface.

“Wow, you look like you’re carrying a prop.” I felt unmasked.

“Our false self is who we think we are. It is our mental self-image and social agreement, which most people spend their whole lives living up to—or down to.”

The “clothing” of yourself with these bandages, in Merton’s phrase, also means that if you are not ever vigilant, those bandages may occasionally slip, and reveal your underlying true self to others.

There were two choices: to be honest and share myself with another person, or to lie and conceal myself from my friend. I chose the second option. “What?” I said.

self, “I was just having a bad day, you know?” The false self had reasserted itself. Those bandages would not fall away for many years.

Merton’s early journals and letters are filled with a confidence that unsuccessfully masks a deep longing for a place to belong.

Merton continues to meditate on what kind of monk he is intended to be,

His spiritual journey was far from complete when he entered the doors of the abbey. In many ways it had just begun.

“discovering myself in discovering God.”

finding God means allowing ourselves to be found by God. And finding our true selves means allowing God to find and reveal our true selves to us.

Simply put, one attempts to move away from those parts of ourselves that prevent us from being closer to God: selfishness, pride, fear, and so on. And one also tries, as far as possible, to move toward those parts of ourselves that draw us nearer to God.

is, the desire for our true selves to be revealed, and for us to move nearer to God, is a desire planted within us by God.

Karl Rahner: Spiritual Writings, the esteemed Catholic theologian wrote, “Christianity’s sense of the human relationship to God is not one that says that the more a person grows closer to God, the more that person’s existence vanishes into a puff of smoke.” In the quest for the true self, one therefore begins to appreciate and accept one’s personality and one’s life as an essential way that God calls us to be ourselves. Everyone is called to sanctity in different ways—in often very different ways.

the path to sanctity for an extroverted young man who loves nothing more than spending time with his friends cheering on their favorite baseball team over a few beers is probably very different from that of the introspective middle-aged woman who likes nothing better than to sit at home on her favorite chair with a good book and a pot of chamomile tea. One’s personal brand of holiness becomes clearer the more the true self is revealed.

As Richard Rohr writes, “Once you learn to live as your true self, you can never be satisfied with this charade again: it then feels so silly and superficial.”

he asked, “Well, that’s fine, but what happens if your true self is a horrible, lying, mean-spirited person?”

his intolerance of others diminished over time.

In his journal, he recounts his reactions as he observes the crowds observing some notable paintings that have been sent over for exhibition at the Fair. It is a merciless portrait of Merton’s fellow human beings, who are depicted as far less sophisticated than the writer.

There were a lot of people who just read the name: “Broo-gul,” and walked on unabashed….They came across with the usual reaction of people who don’t know pictures are there to be enjoyed, but think they are things that have to be learned by heart to impress the bourgeoisie: so they tried to remember the name.