More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

October 17 - November 1, 2025

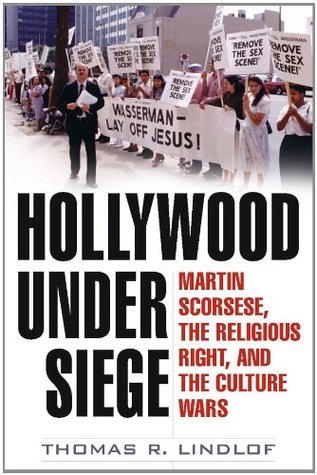

Reports of impressive crowd sizes lend credence to the organizers’ claims that their cause has broad-based support; they also reverberate within a movement itself, stirring strong feelings of community among members and helping attract others to the cause.

An extraordinary crowd can even make history, persisting in the collective memory for decades:

A smaller crowd, on the other hand, is usually all it takes to consign stories of protest to the back pages or push them off the media agenda altogether. It can also signal a setback—if not an abject failure—of the group’s message, deflating the spirits of organizers and foot soldiers alike.

The Last Temptation of Christ was in fact one of the first instances—and is, in many respects, still the prototype—of the strategic employment of certain practices for calibrating (or manipulating) a culture war drama.

Creative projects now usually come from writers, directors, and performers who have proven themselves capable of skillfully probing the boundaries of social conventions, moral codes, and good taste.

if moral panics erupt, crisis managers stand ready to frame the terms of the debates and, if necessary, limit the collateral damage suffered by their clients.

Advocacy groups also depend on a steady flow of provocative content to advance their causes.

Even if such groups do not actually foment culture war flare-ups, many of them are ever on the lookout for media products that can be vilified for violating the transcendent values they hold dear.

professional accomplices are required at least as much as true believers for a crisis to go to full incandescence.

The danger of this path, however, lies in its essential unpredictability.

there is always the chance of misplaying (or misunderstanding) their roles in the drama.

For the first time, a film coming out of the Hollywood system dealt seriously with Christ’s relevance in the post-Enlightenment age.

The impulse to say something daringly original about the Christ figure has erupted in novels as diverse as D. H. Lawrence’s The Man Who Died (1930), Robert Graves’s King Jesus (1946), José Saramago’s The Gospel according to Jesus Christ (1994), Norman Mailer’s The Gospel according to the Son (1997), Jim Crace’s Quarantine (1999), and Nino Ricci’s Testament: A Novel (2003).

writers take enormous artistic risks when they enter this territory.

it is in the nature of novels to go where a sacred text cannot:

“Whereas religion seeks to privilege one language above all others, one set of values above all others, one text above all others, the novel has always been about the way in which different languages, values and narratives quarrel, and about the...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

One crosses over this existential abyss, Kazantzakis believed, only by acting creatively and fearlessly. And to be able to do that, one must cast off society’s petty illusions—chief among them the institutional Church.

In this view, God is an unfinished project and we are all potentially saviors-in-the-making. But the greatest, most honorable savior was Christ, who gave humankind the best example of how to give oneself over to the creative, vital action of love.

He wanted readers to feel the reality of Christ’s radical intervention in the world and rediscover the liberating power of belief in him.

the city where the children’s fable Little Red Riding Hood was once criticized for the bottle of wine tucked in the wolf’s basket, and The Little Mermaid labeled satanic for the title character’s transformation from sea creature to a female human.

story and characters can be subtly subordinated to his own artistic purpose, provided that in the end he gives the audience the kind of moral closure it expects.

The questions he had asked from an early age were ones he still asked: How do you live this life of compassion? How do you practice the concepts of Christianity outside the Church? How do you go about the act of forgiving people when so many consider it a weakness?

the bright line between the sacred and the profane was erased.

He had in mind a Jesus with a dangerous, demanding message of love to preach; an exceptional human being who struggles fiercely to know what God wants of him; a Jesus who, like himself, often feels like an outsider, but, unlike him, finds the strength to transcend the vicissitudes of life.

Schrader has remarked: “Christianity really is a blood cult and a death cult; as much as they say otherwise and talk about the God of Love, it really does focus on the Passion and the bleeding, and those are the images that hit a child.”

Schrader learned about the polyglot nature of the ancient world, the trading communities where East met West, and realized that Jesus was but one of many roving prophets of the time.

The main theme was the revelation of God to Jesus, captured in the question “What does God want of him, and how?”

Character relationships formed the other thematic armatures of the script.

Finally, Schrader checked off incidents that are featured in the Gospels or that help to move the narrative along—“Is it a critical scene vis-à-vis the biblical story? Is it a theme you can’t get around—the Garden of Gethsemane, you know? Does it have comic relief?”

he threw out the incidents that had no checkmarks and kept the ones with the most checks.

Schrader, he said, “[cut] to the heart of many scenes like a laser in a precise and brilliant restructuring of the material.”

knit the narrative together, adding scenes for exposition and transition,

his belief that the everyday lives of ancient people were so suffused with the spiritual that they probably would have seen, and accepted as reality, extraordinary events.

tried to shape the script around his understanding of who Jesus was, and what he meant to say and do.

Jesus as a true su...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Jesus called on his followers to do the unthinkable.

In writing these and other scenes, Schrader played the part of the provocateur to the hilt.

films are born with cultural references different from the literary works from which they derive.

“A concept—or high concept, as it’s come to be known—refers to an idea that can be summarized in a sentence. And then sold to anyone over the age of seven.”

Wildmon suddenly realized that no matter which of the three network channels he tuned to, he could not avoid exposing his children to shows filled with sex, violence, or profanity.

he promoted “Turn the TV Off Week” among the members of his own congregation.

nonprofit organization, the National Federation of Decency (NFD), its unofficial goal the remaking of the face of the multibillion-dollar television industry.

He found that if the networks were impervious to pressures from outside groups, the advertisers weren’t.

“The whole Christian community,” he began, “has always looked at Christ on the one hand as human and, on the other hand, he has wings and there is an aura about him and he is always in the clouds. So people are reading and they are going to movies looking for both of those things. For humanity on the one hand, but not too much. Because if you give him too much, then somehow he is less divine. [In Kazantzakis’ book] there is a wonderful tension between this being a human being with lots of problems and wrestling with anguish and doubt, and on the other hand, having illusions of grandeur.”

How could Jesus empathize with us, and us with him, if the temptation he faced was abstract, easily shrugged off?

It is that kind of interiorization perception of his temptation that is essentially controversial.”

the precise ways that Kazantzakis chose to portray him as a man whipsawed between human impulses and God’s relentless demands:

It has been tampered with for two thousand years!

just because most people do not want to deal with questions about Jesus’ doubts and temptations doesn’t mean the questions should not be asked.

They simply said that doing an interpretation of the story of Christ that is not true to tradition is in itself an act of blasphemy, is in itself heretical, and you do not have the right to tamper with it.”