More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 16 - September 4, 2024

What is courage? What is strength? Perhaps it is being ready to fight for your nation even when your nation isn’t ready to fight for you.

Most black soldiers in World War II were kept out of combat. Instead, the military often assigned them to service duties such as building roads, driving trucks, sweeping up, unloading cargo, cooking, doing laundry, serving meals, or guarding facilities.

The U.S. military has a long history of racial prejudice, from the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, and right up through World War II.

In a book called The Employment of Negro Troops, considered an official part of U.S. Army history, author Ulysses Lee quotes white officers of all-black units from World War I saying, “The Negro should not be used as a combat soldier” and “The Negro must be rated as second class material, this due primarily to his inferior intelligence and lack of mental and moral qualifications.” No matter how false, these were difficult statements to overcome.

Colonel Howard Donovan Queen, an African-American soldier who served in World War I and was later a commanding officer of the all-black 366th Regiment of the 92nd Infantry Division in World War II, said, “World War I [had been] one big racial problem for the Negro soldier. World War II was a racial nightmare. . . . The Negro soldier’s first taste of warfare in World War II was on Army posts right here in his own country. This in its turn caused considerable confusion in the minds of the draftees as to who the enemy really was.”

In 1939, the Committee for the Participation of Negroes in National Defense was created, led by African-American scholar and historian Rayford W. Logan,

The press release implied that segregation would continue because it had “been proved satisfactory over a long period of years.” It also said that desegregation “would produce situations destructive to morale and detrimental to the preparation for national defense.”

Historically, white men and women have professed and aligned with being supporters of democracy, knowing their ancestors took and assigned lands to European immigrants, enslaving the black population, then fencing, dividing, building, and farming lands occupied by Indigenous people within a racially, ethnically, and diverse America.

African Americans was beginning to change in parts of the country. Readers learned, for example, that more jobs were open to them in the North, even if blacks would not earn the same pay as whites. Southern blacks were encouraged to migrate north, where racism was certainly not gone but was a bit easier to stomach in light of more tolerable living conditions.

“They could call him what they wanted on the train. He didn’t like it, but it didn’t define him. He lived in Harlem now and was free.”

the suggestion of his wife, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, FDR put together a group, informally called the Black Cabinet, to help him understand what black Americans needed from their government.

FDR met with Randolph and Walter White, head of the NAACP. He did not agree to integration, but he did issue Executive Order 8802, commonly called the Fair Employment Act, which prohibited discrimination in the defense industry.

The Order said: “I do hereby reaffirm the policy of the United States that there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.”

FDR’s Black Cabinet, March 1938. Most were community leaders, not politicians. Front row, left to right: Dr. Ambrose Caliver, Dr. Roscoe C. Brown, Dr. Robert C. Weaver, Joseph H. Evans, Dr. Frank Horne, Mary McLeod Bethune, Lieutenant Lawrence A. Oxley, Dr. William J. Thompkins, Charles E. Hall, William I. Houston, Ralph E. Mizelle. Back row, left to right: Dewey R. Jones, Edgar Brown, J. Parker Prescott, Edward H. Lawson Jr., Arthur Weiseger, Alfred Edgar Smith, Henry A. Hunt, John W. Whitten, Joseph R. Houchins.

From Jackson, Mississippi, a group of soldiers wrote to William H. Hastie. He was an African-American judge and scholar who had graduated first in his class from both high school and Amherst College and was dean of the Howard University Law School. Hastie had been asked to serve as the civilian aide to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, fielding issues related to black soldiers.

The soldiers wrote: “We are treated like wild animals here, like we are inhuman. . . . Civilian polices have threatened to kill several soldiers. . . . Lieutenant Bromberg said all Negroes need to be beaten to death. . . . We never get enough to eat.

“We’re not even good as dogs, much less soldiers, even our General on the post hates the sight of a colored soldier.”

When that statement was released to the press — including the black newspapers — it upset a lot of people. With the presidential election coming up, the Democrats were worried that Roosevelt would lose the black vote. In part to make amends, in the weeks leading up to the election, the White House and the War Department announced that black aviation units would be formed, as well as new black combat units in the Army.

Roosevelt promised that blacks would serve in all branches of the armed forces.

Colonel Benjamin O. Davis Sr. — the highest-ranking black officer in the Army — was promoted to brigadier general, becoming the first...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Brigadier General Davis conducted inspection tours of bases that trained African-American soldiers, investigating discrimination and advocating for better treatment when needed, both in the United States and overseas.

Davis urged the military to create more combat units and utilize black soldiers properly. When he discovered combat units that were continually passed over for overseas assignments, he put pressure on the War Department to send them.

Stimson, who seemed to support segregation of the military, was annoyed by the appointment. He wrote in his diary, “The Negroes are taking advantage of this period just before the election to try to get everything they can in the way of recognition from the Army.” In spite of Stimson’s attitude and Hastie’s realization that he “was not really welcomed by the military,” over the next few years Hastie continued to try to persuade the War Department to improve conditions for African-American soldiers.

Sergeant Henry Jones was one of many soldiers who wrote to Mrs. Roosevelt. He told her that the men in his unit were “loyal Americans . . . ready and willing to do their part . . . the fact that we want to do our best for our country and be valiant soldiers, seems to mean nothing to the Commanding Officer of our Post.” Jones was writing on behalf of 121 other soldiers who signed the letter. “We do not ask for special privileges. . . . All we desire is to have equality; to be free to participate in all activities, means of transportation, privileges and amusements afforded any American

...more

The 99th Pursuit Squadron — known as the Tuskegee Airmen — was the first group of black aviators to be trained. They proved to be exemplary pilots. Colonel Benjamin O. Davis Jr., son of Davis Sr., was among the first cadets and became their commander. Davis had applied to the Air Corps six years earlier but had been rejected then based on the explanation that “no black units were to be included.”

The Tuskegee Airmen went on to achieve glory in World War II, flying more than 1,500 missions without ever losing one of their own to an enemy bomber, and earning a collective one hundred Distinguished Flying Crosses.

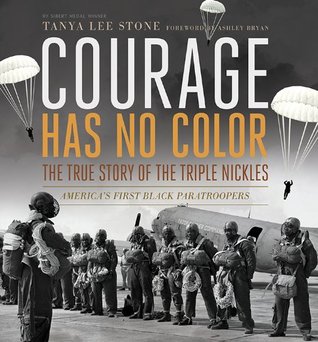

If the Air Corps could produce stellar black pilots, then why couldn’t the Army produce stellar black paratroopers?

Bradley Biggs was the first officer accepted to the 555th.

“Soldiers were fighting the world’s worst racist, Adolph Hitler, in the world’s most segregated army,” historian Stephen Ambrose later wrote.

At his own post, while training to be a paratrooper, Morris experienced the sting of seeing German and Italian prisoners of war buying cigarettes and candy at the post exchange. “Those men,” he later recalled, “prisoners who killed American soldiers . . . [could] buy cigarettes or whatever they wanted to, but we . . . couldn’t go into the post exchange.”

Tuskegee Airman Luther H. Smith was in a German prison camp after being captured when his plane crashed. A German officer confronted Smith. “With utter contempt he said, ‘You volunteered to fight for a country that lynches your people.’” “You might as well have hit me with a heavy stick,” Smith said. The next day, when the officer launched at him again, Smith had his comeback ready: “You people are just as bad. . . . Your German Jews, you lynch them. . . . I am black American. It is my home. I will fight for it because I have no other home, and by fighting for it, I can make America better.”

“If I was able — physically, mentally, every other kind of way, able and willing to serve my country — and my country turned me down on the basis of color, then my country did not deserve me.”

the Double V Campaign, with its slogan “Victory at Home and

Paratrooper training is all about being combat ready.

opinion surveys given by the Army Research Branch (ARB) showed that before the Battle of the Bulge, only 33 percent of white soldiers had a positive response to including blacks in their companies. Afterward, a whopping 77 percent felt favorably about the idea. Brigadier General Davis said that the decision to integrate in the Battle of the Bulge was “the greatest since enactment of the Constitutional amendments following the emancipation [of slaves].” He wanted the ARB’s opinion surveys made public to prove that integration would not cause mass disruption, but those who favored military

...more

With a nation now fearing this enemy, panic won and the unthinkable happened. President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which resulted in more than 120,000 “people of Japanese ancestry” being rounded up and put in internment camps.

They weren’t being sent overseas to fight the war, but they were being sent to fight a threat by the Japanese on American soil. Code name: Operation Firefly.

If I didn’t know about the Triple Nickles, I would never have thought about going to jump school.”

“Just as the Tuskegee Airmen opened the way for black pilots,” he said, “the Triple Nickles opened the way for blacks to become paratroopers.”

The trail the 555th pioneered was not just about paratroopers or smokejumpers. It was about the way people considered race.