More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

November 13 - November 14, 2023

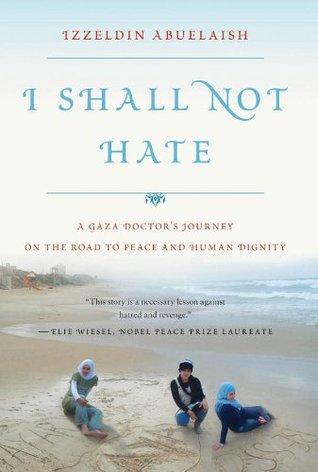

Most of the world has heard of the Gaza Strip. But few know what it’s like to live here, blockaded and impoverished, year after year, decade after decade, watching while promises are broken and opportunities are lost.

Thick, unrelenting oppression touches every single aspect of life in Gaza, from the graffiti on the walls of the cities and towns to the unsmiling elderly, the unemployed young men crowding the streets, and the children—that

This is my Gaza: Israeli gunships on the horizon, helicopters overhead, the airless smugglers’ tunnels into Egypt, UN relief trucks on the roadways, smashed buildings, and corroding infrastructure. There is never enough—not

It is human nature to seek revenge in the face of relentless suffering. You can’t expect an unhealthy person to think logically.

The acts of violence committed by the Palestinians are expressions of the frustration and rage of a people who feel impotent and hopeless.

nothing is spared, and nothing is sacred.

I have long felt that medicine can bridge the divide between people and that doctors can be messengers of peace.

Exactly thirty-five days later, on January 16 at four forty-five p.m., an Israeli tank shell was fired into the girls’ bedroom, followed swiftly by another. In seconds, my beloved Bessan, my sweet, shy Aya, and my clever and thoughtful Mayar were dead, and so was their cousin Noor. Shatha and her cousin Ghaida were gravely wounded.

It used to take an hour’s drive over paved goat trails to get from Gaza to Jerusalem. Today it’s a half-day journey if you’re lucky—if you have an exit pass, if the border remains open rather than suddenly closing, if the bus arrives on time and the traffic isn’t snarled, and if the security officers aren’t giving lessons in patience.

for Palestinians in general and Gazans in particular, traveling is only permitted for a purpose: to study, work, or for medical treatment abroad that is not available in Gaza.

Coincidentally, the plant’s name in the Arabic language means “patience and tenacity.” Like the roots of the stubborn sabra that have defied the shovel of deportation, the people of Gaza have had to dig in and seek survival.

My father never gave up the ownership papers of his farm. Even today, though the land at Houg is known as the Sharon Farm and Ariel Sharon is listed as the owner, the deed and tax papers stay with me.

Today Gaza is a strip of land approximately twenty-five miles long. It is about four miles wide at its narrowest and almost nine miles at its widest. Israel controls everything—the air, the water, the land, the sea.

“His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

Jews were a minority in Palestine, outnumbered by Arab Christians and Muslims. All of the rights of all of the non-Jewish people in the region were prejudiced by their expulsion from their homes and farms.

Like most Palestinian children, I didn’t really have a childhood.

Until I was ten, my family, which eventually numbered eleven (two parents, six boys—I was the eldest of them—and three girls), lived in one room that measured about ten feet by ten feet. There was no electricity, no running water; there were no toilets in the house. It was dirty. There was no privacy.

When we were ready for bed, she’d wipe out the dish bucket and use it as a cradle for the baby to sleep in. One night my brother Nasser was acting up, aggravating my mother. She reached out to slap him, but he got away from her and she leaped up to chase after him. He jumped into the dish bucket to escape her, landing on top of the baby. The baby, my sister, who was only a few weeks old, died.

I don’t really know how my father bore it—the conditions we lived in—given that he had lived the first part of his life on the family farm where there was plenty of food and just as much pride.

The truth is, my most powerful memories of growing up in Jabalia Camp are of the stench of the latrine, the gnawing ache in my hungry stomach, the exhaustion from selling milk in the very early morning to earn that little bit of money that was so essential to my family,

Survival doesn’t allow time for poetic reflection.

I would sit on the floor of our one-room house doing my homework by the light of an oil lamp as my younger siblings tussled about.

The Palestinian mother is the author of the survival story of the Palestinian people. She is the heroine, the one behind the successes. She feeds everyone before taking food for herself. She never gives up, and she pushes against the barriers holding her children back.

I wonder how those soldiers must have felt, pointing their murderous weapons at little children still rubbing sleep from their eyes and clinging to their mothers in doorways.

The houses along the street were simple, small, even primitive, but they were all we had. Sharon saw them simply as obstructions on a road that he wanted widened.

The soliders ordered the people on my street to leave our houses and stand together and wait. About eight hours went by. At dawn they said we had a couple of hours to empty our houses.

We decided to stay. But because we refused to relocate, Sharon denied us compensation for our home.

In one hour we witnessed the demolition of our house and about a hundred others that were in the way of the tanks.

How come a Palestinian child does not live like an Israeli child? Why do Palestinian children have to toil at any hard job just to be able to go to school? How is it that when we are sick, we can’t get the medical help Israeli kids take for granted?

“I am a Palestinian from the Jabalia refugee camp in the Gaza Strip, and I am the same as you.”

The humiliation of the occupation knew no bounds; the Israeli soldiers would do stupid things like forcing a Palestinian to walk like a donkey just to make fun of him.

Any small incident, real or imagined, could have set off the outrage, but as far as I could determine, the unrest came mostly from the fact that nothing was being done to alleviate the situation for Palestinians.

Palestinians had been waiting for change, for relief from intimidation and harassment, for twenty years since the Israelis took over in Gaza, and it was not surprising to see violence erupting in our streets.

kids throwing stones were met with soldiers attacking with M16 assault rifles.

It’s not easy to move patients across this divide. A Palestinian ambulance had to bring her to the Erez Crossing. An ambulance from Soroka had to meet her there and make the switch. It was (and still is) difficult to get permission to cross into Israel. Not only that, but the Palestinian Authority had to agree to pay her medical costs before she could leave.

She had never been to Israel before and was afraid she’d be mistreated. But it was Israeli doctors who saved her life.

no matter where in the world we graduate or what language we speak, we leave our differences outside those walls and we are dedicated to saving lives.

The second intifada began in September 2000 when a number of incendiary events came together like a forest fire. Ariel Sharon visited the Temple Mount, the third most holy site in the Islamic world, in a show of “I dare you to try to stop me.”

As a Palestinian, I knew a thing or two about terror. I had been living with it for much of my life.

you cannot ask people to coexist by having one side bow their heads and rely on a solution that is only good for the other side.

People often tell me they admire my patience and ability to be calm and avoid rash and impulsive behavior. I tell them I learned all of it while waiting in line at the Erez checkpoint.

Hatred eats at your soul and takes opportunities away from you. It’s like consuming poison.

The Israelis have even calculated the number of calories a person needs to survive and allow only bare essentials to cross the border into the Strip.

Fruits such as apricots, plums, grapes, and avocados, even dairy products, are suddenly declared nonessential and forbidden to us.

The stiffening embargo, the incursions, attacks, and arrests are playing on the psyches of the people. What’s worse is that we Gazans don’t see the outside world caring much about our plight.

We’ve learned to do without, manage with less, and cope with deprivation over and over and over again—for sixty years now. If anyone thinks this does not have an effect on the physical and mental state of the people, that person needs to come to Gaza to check for himself.

Seventy percent of Gazans are officially below the poverty line, with incomes of less than US$250 per month for a family of seven to nine.

Forty percent are classified as extremely poor, with incomes of US$120 per month or less.

Much of the time, we rely on goods coming through the tunnels that have been dug underground into Egypt, but the tunnels can’t begin to meet the needs of 1.5 million people. What’s more, they’re regularly bombed by the Israeli air force.

Israeli gunboats guard the perimeter, aiming their guns by day and night along the shore and at the small boats of hapless fishermen.