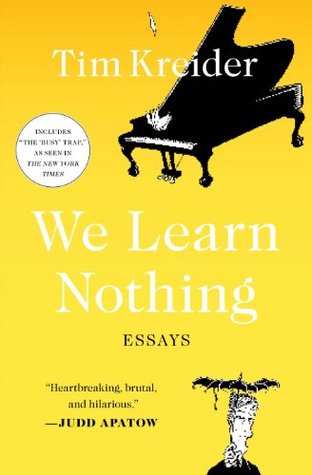

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Tim Kreider

Read between

September 24 - November 7, 2016

I can’t recapture that feeling of euphoric gratitude any more than I can really remember the mortal terror I felt when I was pretty sure I had about four minutes to live. But I know that it really happened, that that state of grace is accessible to us, even if I only blundered across it once and never find my way back.

But I can’t quite bring myself to join in the smirking over more ordinary lechery and weakness—a former governor mooning over his “soul mate” at a press conference, a talk-show host confessing on the air to affairs with his interns.* Whom, exactly, do we think we’re kidding?

The truth is, people are ravenous for sex, sociopaths for love. I sometimes like to daydream that if we were all somehow simultaneously outed as lechers and perverts and sentimental slobs, it might be, after the initial shock of disillusionment, liberating. It might be a relief to quit maintaining this rigid pose of normalcy and own up to the outlaws and monsters we are.

This kind of anarchic, Dionysian love doesn’t give a shit about commitments or institutions; it smashes our illusions about what kind of people we are, what we would and would not do, exposing the difference between what we want to want and what we really want.

I had two epiphanies: 1) I do not even like this person and yet 2) I would sneak off to the bathroom with her right now. With some people, it’s all a foregone conclusion once you get close enough to inhale the scent of their hair.

I have loved women who were saner and kinder than me, for whom I became the best version of myself. But it’s also a relief to be with someone who’s not better than you, who’s just as bad and likes it. With these women, I didn’t have to impersonate a better person than myself; we were complicit, accomplices.

I spent a summer racked with loss over a woman with whom I’d had only four weekends and a lot of phone calls, which we mostly spent listening to each other breathe. I wasted a year of my life torturing myself with jealousy and rage over someone I knew I didn’t want to be with; what I wanted was not to lose her. That passion took these women as its objects as arbitrarily, and as indispensably, as a fetish fixates on an elbow or stiletto or a bathtub full of flan.

a touch of the pathology you require, but not so much that it will destroy you. But, as with drinking just enough to feel mellow and well-disposed toward the world, but not so much that you end up vomiting in the street, this can take some trial and error to calibrate.

Even though those breakups and disentanglements hurt, and it may always make me a little sad to see those women, they are the ones I will love for life, the ones I’d want to have by my deathbed.

The kind of bond I feel with the women I’ve fallen so horribly in love with is more involuntary, as arbitrary and indissoluble as the one that unites the survivors of some infamous disaster. One of my former lovers proposed having T-shirts made as souvenirs for all the participants in/casualties of our affair that would read Armageddon ’97. She finds this funnier than I do.

I learned that making out on the subway is one of those things, like smoking cigars or riding Jet-Skis, that is obnoxious and repulsive when other people do it but incredibly fun when it is you.

Drunkenness and youth share in a certain reckless irresponsibility, and the illusion of timelessness. The young and the drunk are both temporarily exempt from that oppressive sense of obligation that ruins so much of our lives, the nagging worry that we really ought to be doing something productive instead. It’s the illicit savor of time stolen, time knowingly and joyfully squandered. There’s more than one reason we call it being “wasted.”

my friends and I were spending whole days drinking bottomless pitchers of mimosas or Bloody Marys and laughing till we wept on decks overlooking the Chesapeake Bay.

There is no drinking as enjoyable as daytime drinking, when the sun is out, the bars are empty of dilettantes, and the afternoon stretches ahead of you like summer vacation.

Drinking was, among other things, an excellent excuse to devote eight or ten consecutive hours to sitting idly around having hilarious conversations with friends, than which I’m still not convinced there is any better possible use of our time on earth.

I was professionally furious every week for eight years.

Parenthood opens up an even deeper divide. Most of my married friends now have children, the rewards of which appear to be exclusively intangible and, like the mysteries of some gnostic sect, incommunicable to outsiders. It’s as if these people have joined a cult: they claim to be happier and more fulfilled than ever before, even though they live in conditions of appalling filth and degradation, deprived of the most basic freedoms and dignity, and owe unquestioning obedience to a pampered sociopathic master whose every whim is law. (Note to friends with children: I am referring only to other

...more

I have never even idly thought for a single passing second that it might make my life nicer to have a small rude incontinent person follow me around screaming and making me buy them stuff for the rest of my life.

We were both passionately opinionated leftists of the school that holds that political change is best effected through strident ranting over drinks.

I’m not sure whether it is a perversity peculiar to my own mind or just the common lot of humanity to experience happiness mostly in retrospect. I have of course considered the theory that I am an idiot who fails to appreciate anything when he actually has it and only loves what he’s lost.

We mistakenly imagine we want “happiness,” which we tend to picture in vague, soft-focus terms, when what we really crave is the harderedged quality of intensity. We’ve all known (or been) people who returned again and again to relationships that seemed to make them miserable. Quite a few soldiers can’t get used to the lowered stakes of civilian life, and reenlist. We want to be hurt, astonished, reminded we’re alive.

And yet, if I’m allowed any final accounting of my days, I may find, to my surprise, that I reckon those Fridays when I woke up without an idea in my head and only started drawing around noon, calling friends at work for emergency humor consultations, doing frantic Google image searches for Scott McClellan or chacmool, eating whatever crud was in the fridge, laughing out loud at my own inspirations, and somehow ended up getting a finished cartoon in by deadline, feeling like an evil genius and well deserving of a cold beer, to have been among my best.

If I consciously felt anything when I looked up from my work, it was mostly anxiety and guilt about having been so derelict and left everything until deadline yet again. But during the time I was actually focused on drawing—whipping out a perfect line, fluid but precise, gauging the exact cant of an eyelid to evoke an expression, or immersed in the infinitesimal universe of cross-hatching—I wasn’t conscious of feeling anything at all.

an absorption in the immediate so intense and complete that the idiot chatter of your brain shuts up for once and you temporarily lose yourself, to your relief.