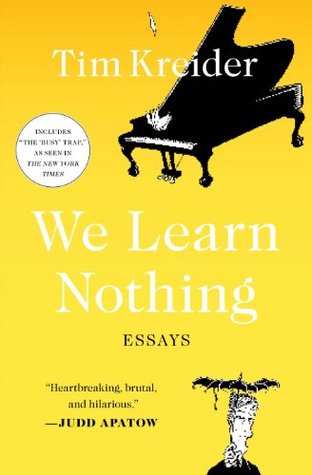

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Tim Kreider

Read between

October 5, 2018 - July 23, 2019

It’s one of the maddening perversities of human psychology that we only notice we’re alive when we’re reminded we’re going to die, the same way some of us appreciate our girlfriends only after they’ve become exes.

You can’t feel crazily grateful to be alive your whole life any more than you can stay passionately in love forever—or grieve forever, for that matter.

Time makes us all betray ourselves and get back to the busywork of living.

I can’t recapture that feeling of euphoric gratitude any more than I can really remember the mortal terror I felt when I was pretty sure I had about four minutes to live.

I’ve demonstrated an impressive resilience in the face of valuable life lessons, and the main thing I seem to have learned from this one is that I am capable of learning nothing from almost any experience, no matter how profound.

If anything, the whole episode only confirmed my solipsistic suspicion that in the story of Me only supporting characters would die, while I, its first-person narrator and star, was immortal.

I don’t know why we take our worst moods so much more seriously than our best, crediting depression with more clarity than euphoria. We dismiss peak moments and passionate love affairs as an ephemeral chemical buzz, just endorphins or hormones, but accept those 3 A.M. bo...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

I sometimes like to daydream that if we were all somehow simultaneously outed as lechers and perverts and sentimental slobs, it might be, after the initial shock of disillusionment, liberating. It might be a relief to quit maintaining this rigid pose of normalcy and own up to the outlaws and monsters we are.

The trick, I suppose, is to find someone with a touch of the pathology you require, but not so much that it will destroy you. But, as with drinking just enough to feel mellow and well-disposed toward the world, but not so much that you end up vomiting in the street, this can take some trial and error to calibrate.

Because it turns out that you can blow life off for as long as you want, but you still have to take the finals.

Memory is also how we learn anything. Even flatworms figure out, after a few bad experiences, to avoid the pathway with the electric shock.

The Soul Toupee is that thing about ourselves we are most deeply embarrassed by and like to think we have cunningly concealed from the world, but which is, in fact, pitifully obvious to everybody who knows us.

This is one reason people need to believe in God—because we want someone to know us, truly, all the way through, even the worst of us.

This is one of the things we rely on our friends for: to think better of us than we think of ourselves. It makes us feel better, but it also makes us be better; we try to be the person they believe we are.

When we die, all our secrets are loosed, like demons departing a body. Whatever subjective self we protected or kept hidden all our lives is gone; all that’s left of us is stories.

It seems like most of the fragments of conversation you overhear in public consist of rehearsals for or reenactments of just such speeches: shrill, injured litanies of injustice, affronts to common sense and basic human decency almost too grotesque to be borne: “And she does this shit all the time! I’ve just had it!”

And they share the same flawed premise as most conspiracy theories: that the world is way more well planned and organized than it really is. They ascribe a malevolent intentionality to what is more likely simple ineptitude or neglect.

Obviously, some part of us loves feeling 1) right and 2) wronged. But outrage is like a lot of other things that feel good but, over time, devour us from the inside out. Except it’s even more insidious than most vices because we don’t even consciously acknowledge that it’s a pleasure.

Outrage is healthy to the extent that it causes us to act against injustice, just as pain is when it causes us to avoid bodily harm. But pain can be perverted into masochism.

As David Foster Wallace asked in his essay on talk radio: “Aren’t there parts of ourselves that are just better left unfed?”

One reason we rush so quickly to the vulgar satisfactions of judgment, and love to revel in our righteous outrage, is that it spares us from the impotent pain of empathy, and the harder, messier work of understanding.

What dooms our best efforts to cultivate empathy and compassion is always, of course, other people.

The truth is, there are not two kinds of people. There’s only one: the kind that loves to divide up into gangs who hate each other’s guts.

Let me propose that if your beliefs or convictions matter more to you than people—if they require you to act as though you were a worse person than you are—you may have lost perspective.

The Referendum is a phenomenon typical of (but not limited to) midlife, whereby people, increasingly aware of the finiteness of their time in the world, the limitations placed on them by their choices so far, and the narrowing options remaining to them, start judging their peers’ different choices with reactions ranging from envy to contempt.