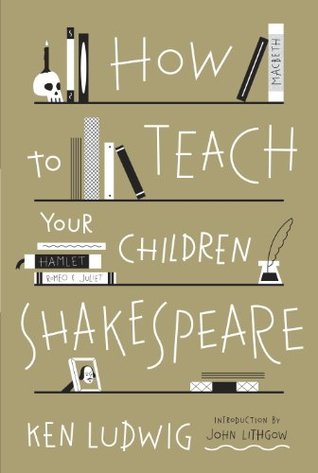

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Shakespeare is, indisputably, one of the two great bedrocks of Western civilization in English. (The other is the King James translation of the Bible.)

Shakespeare is not only creative in himself—he is the cause of creation in other writers. For many of us,

The point is that Shakespeare is like a foreign language. In order to learn it, we need to understand every word, then practice until we feel comfortable. If your children memorize one line at a time, then a short speech, then a longer speech, they’ll become self-assured and then fluent. At that point, Shakespeare will become part of their literary vocabulary.

I have staked my life as a writer on the proposition that the arts make a difference in how we see the world and how we conduct our lives—how we view charity to our neighbors and justice to our communities—and Shakespeare, as the greatest artist in the history of our civilization, has worlds to teach us as long as we have the tools we need to understand him.

Being fluent in Shakespeare from an early age imparts one last advantage that has a significance all its own: It gives my children self-confidence. It gives them the tools, as Falstaff might say, to be witty in themselves and be proud of it.

He’s using a literary device called assonance, which means the repetition of internal vowel sounds in nearby words to create a specific effect. In this case he uses the repeated o to make it sound as if time is dragging along slowly. Have your children exaggerate the sounds. But, Oooo, methinks hoooow slooooow This oooold mooooon wanes!

Poetry, on the other hand, is heightened language that takes us on an emotional, visceral, intellectual journey every time we say it out loud.

This is created through the intellectual content of the words themselves, as well as the sounds of the words and the rhythms of the lines. Prose, with its practical purposes, is often (though not always) operating on the surface only.

As my children put it, Shakespeare’s poetry has a heartbeat running through it that they can feel when they read it aloud.

Sir Peter Hall, likens Shakespeare’s manipulation of iambic pentameter to the way a great musician plays jazz. First the musician creates a recurring rhythm to set up the beat. Then he starts riffing, and he brings his art to bear through all the variations that make his interpretation so interesting.

(The technical term for a metaphor where something closely associated with a subject is substituted for it is metonymy.)

Of course they will, but that’s the beauty of a good love story: The author holds off the final partnering until the last possible moment.

In Western literature, this soliloquy has come to epitomize the meaninglessness and despair that lurk at the center of the human condition. It is short, profound, and terrifying.

What I often say to my children, particularly when we’re going to see a performance of Shakespeare, is that they shouldn’t worry if they don’t understand every word, or even every full speech. They should let the language roll over them, the way waves roll over you in the ocean. There will always be time to analyze later.

Shakespeare has chosen to emphasize the w sound (well … world … wide) to approximate an old man’s speech. His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide And he has chosen the words shrunk shank in order to make us slow down as we say the line, just as the pantaloon is slowing down as he walks.

When we experience a work of art that has genuine value—when we look at a significant painting or watch a performance of a well-written play—we see it differently depending on who we are by nature and where we are in the trajectory of our own experience. Great art changes with us as we and the world grow older.

this most excellent canopy, the air, look you, this brave o’erhanging firmament, this majestical roof, fretted with golden fire—why, it appeareth nothing to me but a foul and pestilent congregation of vapors.