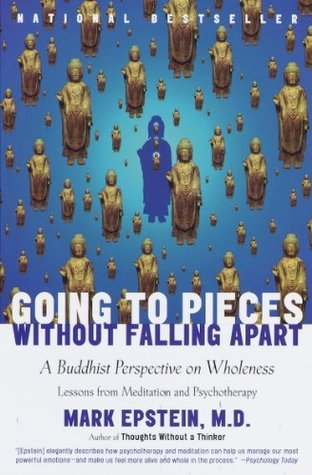

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Mark Epstein

Read between

May 28 - May 31, 2021

Completion comes not from adding another piece to ourselves but from surrendering our ideas of perfection.

“Stop trying to understand what you are feeling and just feel,” they told me. “Absence or presence, it doesn’t matter. Just pay attention to everything exactly as it appears and don’t judge it.”

By appreciating that she could never have what she thought she deserved, she was able to relax. Her emptiness stopped overtaking her only when she stopped taking it personally.

What I had learned from Buddhism was that I did not have to know myself analytically as much as I had to tolerate not knowing.

Winnicott taught that to go willingly into unknowing was the key to living a full life.

Focus on the emptiness, the dissatisfaction, and the feelings of imperfection, and the character will get stronger.

Learn how to tolerate nothing and your mind will be at rest. Psychotherapy tends to focus on the personal melodrama, exploring its origins and trying to clean up its mess. Buddhism seeks, instead, to purify the insight of emptiness.

The emphasis in Buddhism on acceptance and meditation rather than talking and analyzing is something that Western therapy can learn from.

We must learn how to be with our feelings of emptiness without rushing to change them.

As the Buddhist traditions always insist, if we look outside of ourselves for relief from our own predicament, we are sure to come up short. Only by learning how to touch the ground of our own emptiness can we feel whole again.

attachment and aversion,

Only by cultivating a mind that does neither, taught the Buddha, can transience become enlightening.

In the Buddha’s teachings on transience, his point is that everything is always changing. When we take loved objects into our egos with the hope or expectation of having them forever, we are deluding ourselves and postponing an inevitable grief. The solution is not to deny attachment but to become less controlling in how we love. From a Buddhist perspective, it is the very tendency to protect ourselves against mourning that is the cause of the greatest dissatisfaction. As the great thirteenth-century Japanese Zen master Dogen wrote in his discussion of what he called “being-time,” it is

...more

In Buddhism, we must surrender the ego so that we can feel our connection to the universe. We do not move toward greater separation and individuation in this view; we move toward love and death.

Just as separation and connectedness make each other possible, so do the male and female elements of doing and being. One is not “primary,” nor is one always preferable, yet we are deficient if we cannot go freely from one mode into the other.

The antidote to hatred in the heart, the source of violence, is tolerance. Tolerance is an important virtue of bodhisattvas (enlightened heroes and heroines)—it enables you to refrain from reacting angrily to the harm inflicted on you by others. You could call this practice “inner disarmament,” in that a well-developed tolerance makes you free from the compulsion to counterattack. For the same reason, we also call tolerance the “best armor,” since it protects you from being conquered by hatred itself. THE DALAI LAMA

Uncovering difficult feelings does not make them go away but does enable us to practice tolerance and understanding with the entirety of our being. As Joseph made clear, it is not just the mother that has to be released from perfection. It is everything.

Eightfold Path of Right Livelihood—Action, Speech, Mindfulness, Concentration, Effort, Understanding, and Thought—are really parameters rather than way stations on a journey. The spiritual path means making a path rather than following one. It is a very personal process, unique to each individual.

We do not get lots of realizations in our lives as much as we get the same ones over and over.

In the Buddha’s psychological teachings the major obstacle to this kind of spontaneous relating is called delusion. Delusion is the mind’s tendency to seek premature closure about something. It is the quality of mind that imposes a definition on things and then mistakes the definition for the actual experience. Delusion would have me believe that I was my anxiety and that I was forever isolated as a result. Motivated by fear and insecurity, delusion creates limitation by imposing boundaries. In an attempt to find safety, a mind of delusion succeeds only in walling itself off.

Learning to transform obstacles into objects of meditation provides a much-needed bridge between the stillness of the concentrated mind and the movement of real life. As the practitioners of many martial arts often put it, we must learn to respond rather than react.

In coping with the world, we come to identify only with our compensatory selves and our reactive minds. We build up our selves out of our defenses but then come to be imprisoned by them. This leaves us feeling dissatisfied, irritable, and cut off. In our misguided attempts to become more self-assured, we tend to build up our defenses even more, rather than disentangling ourselves from them.