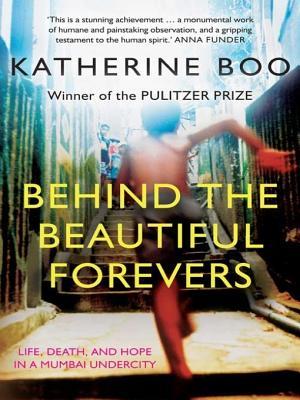

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

April 20 - April 24, 2020

Sonu was enrolled in seventh grade at Marol Municipal. Though he couldn’t go to class because of his work, he registered for school annually, studied at night, and returned at year’s end to take exams.

A white-suited cocaine dealer named Ganesh Anna did a galloping business at the airport, and twice a week sent some of his distributors—Annawadi men in their early twenties—to pick up the bulk cocaine in another suburb. Though Ganesh Anna paid the police to stay off his back, the constables weren’t satisfied with their cut. In return for good information about the time and place of drug buys, they would leave Kalu’s trash pilferings alone. Kalu kept a scrap of paper with the officers’ cellphone numbers in the side pocket of his cargo pants—red-and-brown camouflage, Mirchi castoffs.

OFFICIALLY, THE SAHAR police precinct was among the safest places in Greater Mumbai. In two years, only two murders had been recorded in the whole precinct, which included the airport, hotels, office buildings, and dozens of construction-site camps and slums. Both murders had been promptly solved. “All murders we detect, 100 percent success,” was how Senior Inspector Patil, who ran the Sahar station, liked to put it. But perhaps there was a trick to this success rate: not detecting the murders of inconsequential people.

The police inquiry into her son’s death was closed as swiftly as the inquiry into Kalu’s death had been. In the public record, Sanjay Shetty would be neither a vulnerable witness to a murder nor the victim of police threats and beatings. He would be a heroin addict who had decided to kill himself because he couldn’t afford his next fix.

Sunil felt certain that Air India security guards had murdered Kalu upon catching him in their recycling piles.

Vijay, the middle-class hero of the Civil Defense Corps, who had once gripped her hand. “In my next birth, you can be my wife,” he had recently told her. “Not this time.”

Under it, private developers were granted rights to build on slum land only if they agreed to construct apartments for those slumdwellers who could prove they’d lived in their huts since 1995 or 2000, depending on the slum.

Asha dispatched her son Rahul to supervise as the men dragged the tiny, flailing Geeta out into the slumlanes by her hair, dumped her belongings into the sewage lake, called her a whore, and poured kerosene over her last bag of rice. Sobbing, Geeta’s young children had crouched to pick up the spoiled rice grains, one by one.

The previous week, a Congress Party truck had pulled up outside Annawadi, and workers unloaded eight stacks of concrete sewer covers. A crowd amassed on the road, excited at the pre-election gift. Thanks to Priya Dutt’s party, the slumlanes would have no more open sewers. A few days later, the Congress Party workers returned in the truck. Instead of installing the sewer covers, they reclaimed them. The covers were needed in one of the district’s larger slums, where the prop might influence a greater number of voters.

While Asha and her husband had voter cards and I.D. numbers that allowed them each two votes, in two different precincts, many non-Maharashtrians in Annawadi had yet to secure their one vote. Zehrunisa and Karam Husain were local record holders in disenfranchisement, having spent seven years trying unsuccessfully to register to vote.

Why don’t more of our unequal societies implode?

Having proved myself ill-suited to safe cohabitation with an unabridged dictionary, I had little to lose by pursuing my interests in another quarter—a place beyond my so-called expertise, where the risk of failure would be great but the interactions somewhat more meaningful.

To me, becoming attached to a country involves pressing uncomfortable questions about justice and opportunity for its least powerful citizens. The better one knows those people, the greater the compulsion to press.

Tripathi, a brilliant young woman who had studied sociology at Mumbai University, joined the project as a translator. She was skeptical of a Westerner writing about slumdwellers, but her attachments to Annawadians proved greater than her reservations. She quickly became a fierce co-investigator and critical interlocutor; her insights litter this book. Together,

I found Annawadi children to be the most dependable witnesses. They were largely indifferent to the political, economic, and religious contentions of their elders, and unconcerned about how their accounts might sound.