More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 9 - December 10, 2022

Religion is our human response to the dual reality of being alive and having to die.

course, I am a heretic. The word hairesis in Greek means choice; a heretic is one who is able to choose. Its root stems from the Greek verb hairein, to take. Faced with the mystery of life and death, each act of faith is a gamble. We all risk choices before the unknown.

A person has no religion who has not slowly and painfully gathered one together, adding to it, shaping it; and one’s religion is never complete and final, it seems, but must always be undergoing modification.

In his response to Reid’s sermon, D. H. Lawrence opens a clearer, wider, and more expansive window on the subject. For him, religion has little to do with a body of beliefs or practices; it represents a gradual process of awakening to the depths and possibilities of life itself.

If religion is our human response to the dual reality of being alive and having to die, Unitarian Universalism might best be described as a life-affirming rather than death-defying faith. Yet to affirm life, we must also face death, and struggle to make sense of both.

Offering religious security blankets and heavenly insurance policies, many faiths base their considerable appeal ona denial of death. They reduce this life to preparation for the next, potentially finer life. I cannot accept their gambit. The price for defeating the presumed enemy is too great. By refusing to accept the dispensation of death as a condition for the gift of birth, life’s intrinsic wonder and promise are diminished.

We were immortal, until we became interesting.

It happens when we awaken to the fact that life is not a given—not something to be taken for granted, or transcended after death—but a gift, undeserved and unexpected, holy, awesome, and mysterious.

Elsewhere he writes: It will not need, when the mind is prepared for study, to search for objects. The invariable mark of wisdom is to see the miraculous in the common. What is a day? What is a year? What is summer? What is woman? What is achild? What is sleep? To our blindness, these things seem unaffecting. We make fables to hide the baldness of the fact and conform it, as we say, to the higher law of the mind. [But to the wise] a fact is true poetry, and the most beautiful of fables.

If angels may be defined as the incarnation of the divine in the ordinary, awakening to the miracle of life entails not so much a discovery of the supernatural, but rather a discovery of the super in the natural.

As long as we take life for granted, our regard for it is cheapened and this affects the way we treat others, even those closest to us. Part of being born again, in a Unitarian Universalist way, lies in waking up to the fact that all of life is a gift. The world does not owe us a living, we owe the world a living, our own.

By this interpretation, redemption has little to do with escaping death. Instead, it involves discovering and acting upon life’s hidden yet abundant richness.

Perhaps a more organic metaphor would serve even better. Barbara Holleroth, a Unitarian Universalist pastoral counselor, writes, “It is sometimes said that we are born as strangers into the world and that we leave it when we die. But in all probability we do not come into the world at all. Rather, we come out of it, in the same way that a leaf comes out of the tree or a baby from its mother’s body. We emerge from deep within its range of possibilities, and when we die we do not so much stop living as take on a different form. So the leaf does not fall out of the world when it leaves the tree.

...more

Yet I also knew that mere secular existence often does little better. I had a yearning for community and transcendent values. In short, I wanted an honest religion, one that could both, as Reinhold Niebuhr once said, “afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted.” But I could hardly have expressed that yearning then.

“Why should not we enjoy an original relation to the universe?” he had asked. “Why should not we have poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs? The sun shines also today. Let us demand our own words and law and worship.” His questions (which were also mine) had helped to shape, prophetically, this rather untraditional religious tradition.

appreciate most within it are the individuals—including some long dead whose response to life’s questions served to open the way for people like me. Among our prophets are Margaret Fuller, the pioneering advocate for women’s rights and Emerson’s friend; William Ellery Channing, the Unitarian minister who inspired both Fuller and Emerson; and John Murray, the founder of American Universalism, and his wife, Judith Sargent Murray. Their transforming experiences tell us much about this first source of our liberal faith.

She had “breadth and richness of culture,” as one male friend said, “shown in her allusions or quotations, easy comprehension of new views, just discrimination, and truthfulness.” She was also fun—full of “saucy spriteliness,” a wit that extended to satire, and an intensity and self-assertion that seemed to attract and repell at once. Most young men were more than a little frightened of her.

“Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might.” She began to write more intensely—letters, articles, a translation of Echermann’s Conversations with Goethe. She even planned a biography of the German poet.

“I accept the Universe!” she exclaimed. To which Emerson’s friend Thomas Carlyle commented, “By gad, she’d better!” Fuller was often mistaken as some sort of egoist because she was not a conventional, demure, nineteenth-century woman. But what she was really saying Carlyle himself had said, that existence requires an “everlasting Yea,” an affirmation stronger than all life’s negations.

The great end in religious instruction, is not to stamp our minds upon the young, but to stir up their own; not to make them see with our eyes; but to look inquiringly and steadily with their own; not to give them a definite amount of knowledge, but to inspire a fervent love of truth; not to form an outward regularity, but to touch inward springs; not to bind them by ineradicable prejudices to our particular sect or peculiar notions, but to prepare them for impartial, conscientious judging of whatever subjects may be offered to their decision; not to burden the memory, but to quicken and

...more

“The Universalists believe that God is too good to damn them,” said Starr King, “whereas the Unitarians believe they are too good to be damned!” And indeed our Universalist heritage continues to challenge the Unitarian tendency to be “fit but few.” We are challenged to reach out to all sorts and conditions of people, to be open to the individual character of all human religious experience.

“Experience,” the most sad but most profound essay he ever wrote. “We wake,” he said, “and find ourselves on a stair; there are stairs below us which we seem to have ascended; there are stairs above us, many a one, which go upward and out of sight.”

In Unitarian Universalist congregations we do not try to make one another fit a given pattern of experience. But we do discover together that there are religious dimensions in all our varied human experience.

Sometimes it takes something very close to our own death, or the death of someone we love, to break through our usual defenses and remind us what a gift it is to be alive and to be able to love.

For if there is one God (truth or reality) for all, and if we all have equal access to this, regardless of the specifics of our respective faiths, the only thing that differentiates one person’s righteousness from that of another is reflected in his or her deeds.

“Is there nothing worth risking one’s life for? Are there no dreams or goals so important that we risk our own destruction to gain them?”

“We need not think alike to love alike.”

courageous. Often this means doing or saying something that has no real moral authority. Such authority can only be won through concrete acts of service and through the tough work of building a moral consensus through study, dialogue, and support for diverse witness. Although it is tempting to try to make a big “splash,” I believe it is better to rely on what William James called “those tiny invisible molecular moral forces that work from individual

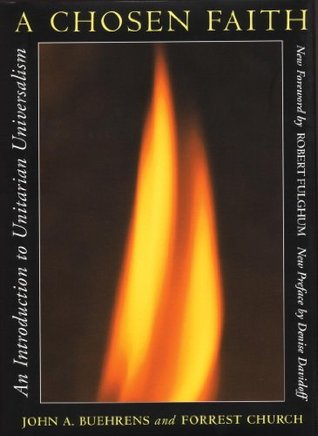

Its light evokes the eternal flame in the ancient temple at Jerusalem, as well as the lamp of reason, and the flames on the many altars of faith—all very real sources of our living tradition.

I think that one of our most important tasks is to convince others that there’s nothing to fear in difference; that difference, in fact, is one of the healthiest and most invigorating of human characteristics without which life would become meaningless.

The light of God (“God” is not God’s name, but our name for that which is greater than all and yet present in each) not only shines down upon us, but also out from within us.

Religion is dangerous, of course, because its power is independent of the universal validity of its claims. Every generation has its terrorists for Truth and God, hard-bitten zealots for whom the world is large enough for only one true faith. They have been taught to worship at one window, and then to prove their faith by throwing rocks through other peoples’ windows. Tightly drawn, their logic makes a demonic kind of sense: (1) religious answers respond to life and death questions, which happen to be the most important questions of all; (2) you and I may come up with different answers; (3) if

...more

Among other things, this theology suggests that we must acknowledge the partial nature of our understanding; respect insights that differ from our own; and not only defend the rights of others to believe their own truths so long as they do not deny us the same privilege, but also credit them with a measure of truth (with a small t) even though it may conflict with the truth that we embrace.

We draw inspiration from other religions as well as our own. Within our churches we acknowledge the presence of many different windows, celebrate a wide variety of festivals in an attempt to divine the essential meaning of each, and—at our best—truly welcome and respect the insights of others.

“Were I to be the founder of a new sect, I would call them Apiarians, and, after the example of the bee, advise them to extract the honey of every sect.”

One Truth, many truths; one God, many faiths; one light (Unitarianism), many windows (Universalism). This is why we number as one of the sources for the living tradition we share “wisdom from the world’s religions which inspires us in our ethical and spiritual life.” Among other things, it reminds us to be humble, especially when we are sure we are right.

We made our own decisions about where we belonged in the religious world before we ever met each other, and we have never tried to convert the other. (Well, almost never.) For the most part our differences are not threatening; they enrich and deepen our own understandings of religious living.

Conversion is one answer to differences in religious background. Two affiliations is another. The common ground of a Unitarian Universalist congregation represents a third. This may begin as a compromise, but the solution works best when it does not end there. In our congregations, rather than avoid differences in background and spirituality, each partner can encourage the other in an ever-deeper process of spiritual growth.

when it comes to religion novelty is not a particularly strong credential; as often as not, it suggests shortsightedness, impermanence, and faddishness. On the other hand, hidebound religions, dogmatically fixed to some ancient creed formulated centuries ago in response to theological, political, and sociological conditions of another age and culture, escape the dangers of novelty, but at an unacceptable price.

him the Bible was written not by God, but by inspired people, drawing from both history and experience, who sought to understand better the larger meaning of life and death.

our fourth source: Jewish and Christian teachings which call us to respond to God’s love by loving our neighbors as ourselves.

WE ONLY KNOW two things for certain: “I am,” and “I will die.” Religion is our response. Whether it is spoken or unspoken, conscious or unconscious, inherited or chosen, we all have a religion of some sort or another, for religion is not merely a matter of belief or affiliation. It is a matter of how we chose to live.

Unitarian Universalism aspires to a special form of religious community—one in which individuals are never asked to check their minds at the church door, but in which they offer one another the possibility of rediscovering an authentic and personal spirituality. We remind ourselves that how we live does matter, even after we die. We are related, forever, to one another.

Unitarian Universalism has one goal above all others: to make the religious more rational and the rational more religious.

“Spirituality,” he writes, “is a potential aspect of all life. It’s not a given quantum, nor is it to be found in exclusive places. We bring it into existence through the relational dimensions of our being. The spirit when it’s unlocked moves us towards others [and] helps us feel responsible for the well-being of the world.”

We may differ widely in our personal religious orientations, but the sense of common purpose in relating mind and spirit is all-inclusive.

“The religion that is afraid of science dishonors God and commits suicide. It acknowledges that it is not equal to the whole of truth, that it legislates and tyrannizes over a village of God’s empire, but it is not the universal immutable law. Every influx of atheism, of skepticism, is thus made useful as a mercury pill assaulting and removing a diseased religion, and making way for truth.”

From all that dwells below the skies, Let faith and hope with joy arise, Let beauty, truth, and good be sung Through every land by every tongue. —Unitarian Universalist doxology

If orthodoxy (which literally means “right teaching”) proclaims a single, authorized set of answers, we celebrate instead the open mind.