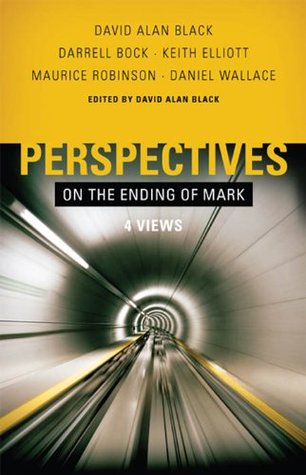

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 10 - February 14, 2019

Thus it was that more than 150 students and scholars of the New Testament journeyed from many parts of North America and Europe to the campus of Southeastern Seminary to hear a formal discussion on the question of the originality of Mark 16:9–20.

presuppositions for a few minutes. Two of mine are that, of the four Gospels, Mark wrote first and John wrote last. As well, I hold to the Doddian school that John was not at all dependent on the Synoptic Gospels; in fact, he was most likely unaware of their specific contents, possibly even of their existence.

There are at least three important presuppositions to address.

Griesbach Hypothesis,

The two-gospel hypothesis is that the Gospel of Matthew was written before the Gospel of Luke, and that both were written earlier than the Gospel of Mark. It is a proposed solution to the Synoptic Problem, which concerns the pattern of similarities and differences between the three Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. From wikipedia

Dr. Wilbur Pickering said, when he was the president of the Majority Text Society, concerning the possibility that the ending of Mark was lost:

If, however, the doctrine of preservation is not part of your credo, you would be more open to all the textual options. I, for one, do not think that the real ending to Mark was lost, but I have no theological agenda in this matter because I don't hold to the doctrine of preservation. That doctrine, first formulated in the Westminster Confession (1646), has a poor biblical base. I do not think that the doctrine is defensible—either exegetically or empirically.12 As Bruce Metzger was fond of saying, it's neither wise nor safe to hold to doctrines that are not taught in Scripture.

Harold Hoehner. He taught the Griesbach Hypothesis—

External Evidence

at least 95 percent of all Greek MSS and ancient versions have the LE. In fact, that number may be too low.

The LE of Mark is not found in the oldest MSS, but it is found in the majority of MSS. And it is found in all the major texttypes—

If Mark's Gospel ends at 16:8, there are no Resurrection appearances by Jesus to his disciples.

Now, let's consider the evidence for the “short” ending—that is, the MSS that conclude the Gospel at 16:8.

Codex Sinaiticus ()—This fourth-century codex is one of the principal witnesses to the Alexandrian texttype. Codex Vaticanus (B)—Vaticanus, also a fourth-century codex, is the most important witness to the Alexandrian text.

Further, although no papyri witness to Mark 16, one might cautiously enlist the support of 75 here. The text of B is closer to that of 75 than it is to any other MS. And 75 is a MS that antedates Vaticanus by at least a century.

Second, it was recently discovered that the scribes of Vaticanus have indicated knowledge of textual variants by using two horizontal dots in the margin next to a line of text where a variant occurs.40There are more than 700 such “umlauts” in the NT of Vaticanus, forty-three of which are in Mark alone. Thus, Codex B marks out half as many variants as the UBS text does! It's almost as if this is an ancient UBS Greek text. This is a remarkable discovery whose implications have yet to be fully explored. But, significantly, there is no umlaut at 16:8.41

Once we get to the fourth century, however, the situation looks decidedly different. Eusebius mentions MSS that end at v. 8 and those that end at v. 20. In discussing the differences between Matthew 28:1 and Mark 16:9, he says: This can be solved in two ways. The person not wishing to accept [these verses] will say that it is not contained in all copies of the Gospel according to Mark. Indeed the accurate copies conclude the story according to Mark in the words … they were afraid. For the end is here in nearly all the copies of Mark. 55

At the beginning of the fifth century, Jerome also notes that the LE is found in “scarcely any copies of the Gospel—almost all the Greek codices being without this passage….”

he adds information not found in Eusebius—viz., that almost all of the Greek MSS that he was acquainted with lacked the LE. This is an important point because Jerome's major work was the Latin Vulgate. He was very familiar with both Greek and Latin MSS. Yet he qualifies Eusebius's statement to refer only to the Greek MSS. The implication may be that the Latin MSS he knew often—or at least more frequently than the Greek—had the last twelve verses. Second, Jerome was well acquainted with several MSS of Mark's Gospel. For example, he quotes from some verses that were found between vv. 14 and 15

...more

Jerome's statement has also been discounted because he included the LE in the Vulgate. Why would he do that? Perhaps for the same reasons that it is included in Bibles today—call it antiquity, tradition of timidity, or not wanting to rock the boat too much. In AD 400, a riot broke out in Tripoli when Jerome's translation of Jonah 4:6 was read publicly. He used the word “ivy” (hederem) instead of the traditional “gourd” (cucurbita) to describe the plant that gave Jonah shelter. Augustine wrote to Jerome about the situation, pleading with him to temper how much he tampered with the traditional

...more

The key issue for internal evidence is whether it is likely that Mark would have written vv. 9–20 or not. The typical points that are raised here are vocabulary, syntax, style, and context

Two recent studies, however, have raised the methodological bar; after a detailed examination, both of them concluded that Mark did not write vv. 9–20.83

The cumulative argument is that these ‘elsewheres’ are all over the map; there is not a single passage in Mark 1:1–16:8 comparable to the stylistic, grammatical, and lexical anomalies in 16:9–20.84

if the text is already suspicious because of external data, then these linguistic peculiarities are strong evidence of the spurious nature of the LE.

But this view was again challenged recently by Clayton Croy, who asked in his well-researched book, The Mutilation of Mark's Gospel, “what kinds of sentences end with gar? …such sentences occur most often in certain kinds of literature…. Sentences ending in gar are much less common in narrative.”

In 9:32, after Jesus' second prophecy about his death and resurrection, Mark tells us that “they did not understand this statement and were afraid to ask him” ( ). Then the pericope just quits: Mark leaves us hanging. And how he leaves us hanging is with the imperfect verb —“they were continually afraid.”

Mark then uses the same imperfect verb in 16:8. Mark 9:32 is a pericope that foreshadows both Jesus' death and resurrection, as well as the disciples' lack of belief in the same.

Very little new evidence of significance has been discovered since the known endings were debated by Burgon, Scrivener, and Westcott-Hort in the nineteenth century.11 No papyri yet exist for this passage; the oldest manuscripts remain /01 and B/03; and the patristic evidence mostly remains unchanged.12 The only subsequent discovery that had any real bearing was that of W/032, which contains the LE plus an expansion previously known from Jerome's late fourth/early fifth-century comments (the so-called “Freer Logion”

Justin evidenced a familiarity with the LE, stating (Apology 1.45) that the disciples, “having gone forth, preached everywhere” ( ). This three-word combination appears only in Mark 16:20,

After the legitimization of Christianity under Constantine, a possible area of concern involved perceived difficulties if certain “sign gifts” might be claimed in support of some revived form of prophetic leadership, particularly neo-Montanism.54 It would be no wonder were certain of the orthodox to have an interest in eliminating an appeal to continuing prophetic signs and wonders, lest a claim of advanced prophetic revelation become destructive of orthodoxy.

This Intermediate Ending by itself is found only in Old Latin MS k (Codex Bobbiensis);

From early times, the Greek Orthodox Church has read the LE for Matins on the Feast of the Ascension.

Elliott, for example, declares, The verb … is not a Markan word. It is however found three times in this longer ending…. Mark does not use the simple form of this verb.

Certainly, occurs exclusively within the LE; elsewhere in Mark only compounded forms with are used. Yet it is fallacious to conclude that Mark could never use the uncompounded form when such might suit his particular purpose.

Fifteen Points of Summary and Conclusion

Any of us who are writers like to impress our intended readers, first by grabbing their attention immediately with a brisk, appropriate opening paragraph. Similarly, we like to conclude our writings with a satisfying climax or summary that our audience feels rounds off our narrative or arguments. The same applies to the biblical authors.

By contrast with these three evangelists, Mark seems rather blunted at both ends.

In this volume we are looking at the way (or ways) in which one of the evangelists, Mark, closed his Gospel. But I am going to extend my investigation by looking at the opening verses of Mark as well. I shall turn to that beginning section a little later.

these fourth-century witnesses, Sinaiticus and Vaticanus, peculiar in their scale and contents but that their texts too were untypical. As far as the endings of Mark are concerned, the examples set by Sinaiticus () and Vaticanus (B), and possibly the other forty-eight copies also prepared for Constantine,4 were not followed. I do not wish to impugn B or even with generic unreliability or to suggest they were maverick copies. B in particular seems to have an ancient pedigree5 yet we cannot ignore its or 's distinctiveness here at the end of Mark.