More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

In the interval between two world wars, sophistication, glamour and light-heartedness obscured an underlying fear of extinction. The big issues were hidden in clouds of cigarette smoke and innovative popular music. Sex was, as ever, the ingredient that would calm the anxious heart. Yet in the music of my father’s era, sexual energy was implied rather than displayed, hidden behind the cultivated elegance of men and women in evening dress.

Roger Daltrey had been expelled for smoking, but was still impudently showing up on campus to visit his various cronies. I’d first met him after he won a playground fight with a Chinese boy.

I loved emulating Jimmy Reed, John Lee Hooker and Hubert Sumlin, Howlin’ Wolf’s guitarist, and I started to develop my own rhythmic style based on a fusion of theirs.

That February, John Entwistle heard that another band was also called The Detours, so we came back to Sunnyside Road after a local show and brainstormed band names for hours. Barney suggested The Who; I suggested The Hair. For a while I hung on to my choice (could I have somehow had an intuition that the word ‘Hair’ was going to launch a million hippies a few years later?). Then, on Valentine’s Day 1964 we made our choice. We became The Who.

We tried a few new drummers, including Mitch Mitchell, who went on to play with Jimi Hendrix. But Keith Moon appeared one day at one of our regular dates at the Oldfield Hotel in Greenford, and as soon as he began to play we knew we’d found the missing link.

Slowly, too, we realised that his fluid style hid a real talent for listening and following, not just laying down a beat.

All good art cannot help but confront denial on its way to the truth.

I kept my tape machine, listening to a few records over and over again: Bob Dylan’s Freewheelin’; Charlie Mingus’s ‘Better Get It in Your Soul’ from Mingus Ah Um (I loved Mingus and was obsessed with Charlie Parker and Bebop); John Lee Hooker’s ‘Devil’s Jump’; and ‘Green Onions’ (although my record was nearly worn out).

The essence of the song ‘My Generation’ had probably been contained in the first, abandoned lyric for ‘I Can’t Explain’, which only Barney ever heard. That first version was a kind of talking blues. The title came from Generations, the collected plays of David Mercer, a dramatist who had impressed me at Ealing.

I worked on ‘My Generation’ all through the summer of 1965, while touring in Holland and Scandinavia (we caused a street riot in Denmark). I produced several sets of lyrics and three very different demos. The feeling that began to settle in me was not so much resentment towards those Establishment types all around my flat in Belgravia as fear that their disease might be contagious.

Home from Sweden we recorded the final version of ‘My Generation’. Kit had heard my first demo, a version that was very much inspired by Mose Allison’s ‘Young Man Blues’, a song we later introduced into our stage repertoire.

Roger, John and Keith loved the new tracks as much as I did, so we incorporated all three of these songs into our repertoire. There were few artists that all four of us respected and enjoyed, and the Everly Brothers were among them.

This sparked the idea for my first opera, later entitled Rael, whose plot deals with Israel being overrun by Red China. Over the next year I developed the story, and planned to complete it as a major full-length operatic composition outside my work for The Who. I hired a Bechstein upright piano from Harrods and installed it in Karen’s bedroom in her flat in Pimlico. I wrote the first orchestrations there for Rael using a book called Orchestration by Walter Piston that I still refer to today.

During one of the October Quick One sessions I met Jimi Hendrix for the first time. He was dressed in a scruffy military jacket with brass buttons and red epaulettes. Chas Chandler, his manager, asked me to help the shy young man find suitable amplifiers. I suggested either Marshall or Hiwatt (then called ‘Sound City’) and I explained the not-so-subtle differences. Jimi bought both, and later I chided myself for having recommended such powerful weapons. I had no idea when I first met him what talent he had, nor any notion of his charisma on stage. Now, of course, I’m proud to have played a

...more

We all miss out on something. I missed out on Parker, Ellington and Armstrong. And if you missed Jimi playing live, you missed something very, very special. Seeing him in the flesh it became clear he was more than a great musician. He was a shaman, and it looked as if glittering coloured light emanated from the ends of his long, elegant fingers as he played. When I went to see Jimi play I didn’t do acid, smoke grass or drink, so I can accurately report that he worked miracles with the right-handed Fender Stratocaster that he played upside down (Jimi was left-handed).

All this impressed me. Psychedelia, drugs, politics and spiritual stuff were getting knitted together all of a sudden, and I did my best to keep up.

Jimi Hendrix’s appearance in my world sharpened my musical need to establish some rightful territory. In some ways Jimi’s performances did borrow from mine – the feedback, the distortion, the guitar theatrics – but his artistic genius lay in how he created a sound all his own: Psychedelic Soul, or what I’ll call ‘Blues Impressionism’.

We advanced a new concept: destruction is art when set to music. We set a standard: we fall down; we get back up again. New Yorkers loved that, and New York fans carried that standard along with us for many years, until we ourselves were no longer able to measure up.

I have tended to reinforce the view that I started to write what eventually became Tommy out of pure desperation. That’s only partly true. I did know that aiming to serve the young men in our audience wasn’t going to work any more, which worried me. But having been in California recently, I also knew that pop audiences would begin spiritual searching, as I had. I could write stories and clearly see theatrical dramas in my imagination. Whether I could realise them was still to be tested. But I began thinking about a project that I wouldn’t allow anyone to divert.

One of the important documents I referred to while writing Tommy was a diagram I had sketched of the beginning and end of seven journeys involving rebirth. I was attempting two ambitious stunts at once: to describe the disciple/master relationship and, in a Hermann Hesse-style saga of reincarnation, to connect the last seven lives of that disciple in an operatic drama that ended in spiritual perfection.

experienced something very peculiar when my daughter Emma was born on 28 March. First the doctor arrived at the hospital, and after explaining how the inducement procedure would unfold he broke Karen’s water to begin the contractions. When I went into Karen’s room to comfort her, the room was filled with angels. I didn’t say anything, worried I was going mad and that I might frighten her. But as I sat holding Karen’s hands and we smiled at each other, the room buzzed with magical energy. I wondered if I was having an LSD flashback. A little later, when Emma was born and first placed in my

...more

A few days later, driving my newborn daughter home, I pulled my head above the parapet: I would do whatever I had to do in order to succeed.

Pop music was evolving, becoming the barometer for a lot of social change. As journalists began to feel less embarrassed about speaking seriously about music I felt as though I was returning to familiar ground, where it was acceptable to speak of Bach, Charlie Parker and Brian Wilson as geniuses without fear of looking nerdy.

Now, suddenly, we were on our own. This isn’t to say we were on top of any pile; but rather, we were out in open water when many of our equally serious peers seemed to be struggling to stay afloat in a sea of pop lightweights like Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich, or The Herd. These bands were perfectly good, but they had no ambition to do anything adventurous. They just wanted hit singles.

In the dark future I visualised in Lifehouse, humanity would survive inevitable ecological disaster by living in air-filtered seclusion in pod-like suits, kept amused and distracted by sophisticated programming delivered to them by the government. As with Tommy, people’s isolation would, in my story, prove the medium for their ultimate transcendence.

The Mysticism of Sound, a book written in the 1920s by Inayat Khan, a musician who became a Sufi spiritual teacher, was my inspiration for the story’s musical solution. The core of my idea was that we could all hear this music – and compose it – if only we would truly listen.

During the rest of the shows on this tour, and a set that followed in the UK, I continued to push hard to create mesmeric arpeggio effects on my guitar, leading into uplifting heavy riffs. Bob Pridden became like a third hand for me. He set up a series of complex fluttering echo effects, and by listening very carefully to what I played he introduced these at perfectly chosen moments. The sound I heard on stage was wonderful, soaring, stratospheric, intoxicating. One otherwise appreciative reviewer remarked that my freeform work went off at too many tangents, but musical tangents were precisely

...more

When you’re part of a gang you soon find the parts of you that don’t fit. These apparent defects can become assets; they’re the things about you that make you interesting and useful.

I had slept for a few hours under Brighton pier in 1964 with my art-school friend, the pretty, strawberry-blonde Liz Reid. We had been together for a riotous night at the Aquarium Ballroom after our gig on the night of a Mod–Rocker street battle on the seafront. Walking along the beach in the dark, under the pier, trying to stay out of the drizzling rain, we’d come across a group of Mod boys in their anoraks. They were giggling as the tide came in, getting their feet wet. We sat with them for a while. We were all coming down from taking purple hearts, the fashionable uppers of the period.

Roger was the helpless dancer; John, the romantic; Keith, the bloody lunatic; and I, needless to say, was the beggar/hypocrite. But the four aspects of Jimmy the Mod’s multiple personality were, in a sense, all to be found in me, and I had always known it.

As it happened Ken was present when we recorded Quadrophenia’s ‘Drowned’ and a stormy rain found a leak in the roof, filling the piano booth with water. ‘Be careful what you pray for,’ said Ken, as we cleaned up. ‘You’re dabbling in the composer’s arts, Pete – both the dark and divine.’

For now I had to accept that my days of playing to kids, and speaking on their behalf, were numbered, and my new patrons, at the back of the theatre, in the cheap seats, were still too distant for me to see them, too far back in the past and too far into the future.

In February Minta sent me a card: Dear Daddy, I miss you very much and I wish you would come home. I always feel unhappy when someone mentions your name. I am sorry to hear about the flu. I heard You Better You Bet on the radio and I like it. It’s not fair! Everybody else has got a dad who comes home at night. I hope you are not too worn out to come and see us again. Love (etc). Minta.

The music computer had landed in two forms. There was the Fairlight CMI, a synthesiser/sampler workstation beloved of New Romantic bands; by the time I started work on White City I had bought my own. The other system was the Synclavier, a digital FM synthesiser with a microprocessor-controlled sequencer. I realised these developments meant I would soon be able to compose and orchestrate very seriously, without the expense of using real orchestras or the barrier of working with orchestrators like Raphael Rudd or Edwin Astley. I found this incredibly exciting, although I have to add that nothing

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

As I tried to hang on to this project, I performed at a concert to raise funds after a volcano had ravaged Colombia. Two session players for The Eurythmics, Chucho Merchan and his partner Anna, a classical cellist, had organised the benefit. Annie Lennox, Dave Stewart and Chrissie Hynde all performed. I was reminded of the finale of Live Aid, when David Bowie, Freddie Mercury and George Michael tried to force their way through the mêlée of artists on stage to get to the front. George had won that time. At the Royal Albert Hall the same thing happened, only the cause was Colombia and the winner

...more

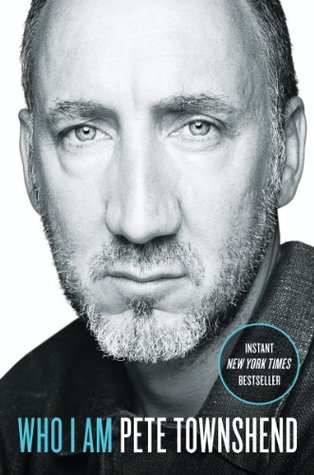

‘You’ve gone all whiter than white and squeaky clean,’ he said. ‘Your fans don’t know who you are any more.’ Had they ever known? Even now I’m still trying to find out who I am.

Mum, who had probably done far more for me in practical terms than Dad, was difficult to love, but loving Dad was always easy.

‘The Limousine’ is a dark murder story in which the evil man who owns the limo fills the airtight passenger compartment with tantalising music combined with poisonous gas. Then he robs, rapes, murders and dumps his customers. I told this tale to an initially rapt audience of about 200. Once I had them in the right frame of mind I got to my theme: when music, converted into digital data, could be compressed sufficiently to pass down a telephone line, music as we knew it would end. We would feel as though we were in control, but we would merely be helpless passengers. Composers and musicians

...more

Vinyl discs, already endangered, would disappear, as would analogue tape. The CD would be unnecessary. We would use computers, some as small as a watch, to listen to music and share it, and we would be overwhelmed by the sheer volume of sounds we were exposed to. Unable to distinguish good from bad, we would, in the matter of music – metaphorically speaking – be gassed, robbed, raped and murdered. Our luxurious, comfortable limousine was really a hearse.

At our New Year’s Eve party I poured wine all evening for my friends, flirted with some of the women and wondered what it would be like to live the reptilian life of a retired rock star, trapped in an inner world of pain and self-doubt.

With Iron Man I’d overworked the songs so they sometimes came across without enough edge, and seemed almost lightweight.

At our house in Twickenham I had moved into my studio, The Cube, aka the ‘garden shed’. It lacked a real kitchen, the bathroom was dowdy and the bedroom tiny.

After a show in San Francisco I talked to Eddie Vedder, the lead singer of Pearl Jam. He was having problems adjusting to fame and was thinking about going back to being a surfer. I gave him my philosophy: we don’t make the choice, the public does. We are elected by them, even if we never stood for office. Accept it.

Nevertheless, I trust in Britain and its democratic process. I am proud that what I do provides jobs, and although I am wealthy and privileged, in my heart and my actions I am still a socialist and activist, ready to stand by the underdog and the beaten down, and to entertain them if I can.

I have moved on. I have always carried within me a defiant, sometimes argumentative and combative pride. It still sits very close to the surface of my psyche, just under the skin, ready to flare up in anger, to leap out and fight. It is in my soul.

I dedicate this book to the artist in all of us. This is as much a note to myself as one to you. Play to the gods! In showbusiness the ‘gods’ are the seats right at the back of the theatre, the tough ones, where people got in cheaply and can’t see or hear properly, and chat between themselves and eat lots of popcorn.