More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

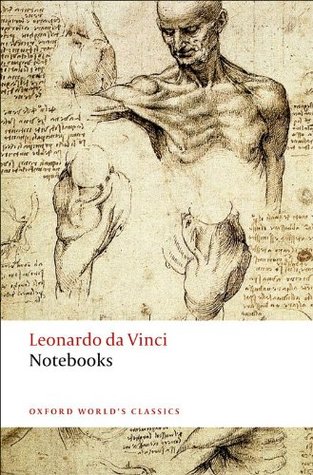

LEONARDO’S notebooks are amongst the most remarkable survivals in the history of human culture. There is nothing quite like them in art, science, and technology. The extraordinary fluency of his thought, unconstrained by disciplinary boundaries, and the brilliance of his graphic techniques are unrivalled. Probably about four-fifths of what he wrote has disappeared, but what remains is extraordinary in range and depth.

Making any selection from Leonardo’s 6,000 or so surviving pages (plus those that are only known in the Treatise) is a real problem. Which Leonardo do we present? The artist, the scientist, the engineer, the natural philosopher, the author of literary snippets …? The underlying difficulty is that although Leonardo and his age would have recognized some of the terms we use, such as painter, sculptor and engineer, many of the professional categories we take for granted post-date the Renaissance. No one went to a college to learn to be an engineer or an architect. Leading masters of many trades

...more

Irma Richter’s compact volume of Leonardo’s writings has provided generations of readers with their most accessible introduction to Leonardo’s own voice and to key documents of his career.

what we have in his notebooks shows us how he approached his life and work, what interested him, what obsessed him and why. They are the key to understanding how he thought.

Little is known about Leonardo’s early life. He was born in 1452, the illegitimate son of Ser Piero di Antonio da Vinci, a leading notary, and Caterina, a young farmer’s daughter. His birthplace of Vinci lies in the hills of Tuscany west of Florence where agriculture dominated the economy.

Leonardo would later write about exploring this countryside as a child and his love of nature, which would become a dominant feature in his later investigations, began with this early exposure. Leonardo was probably taken to Florence by his fath...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Italy in the mid-fifteenth century was not the united country we know today, but a collection of many states with differing forms of government, including several northern states each run by a signore or lord; the Papal States under the control of the pope; larger kingdoms, such as Naples; and a number of important city-state republics including Florence and Venice. The political fragmentation of Italy meant that centres of culture grew up not only in Florence, Venice, and Rome but also in small states governed by ru...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

On an intellectual level, in Florence and the rest of Italy, the humanist revival of classical Roman culture was well established and almost every major Italian city considered itself the daughter of Rome, using imperial or republican Rome as a model depending on their own type of government. The works of great thinkers such as Euclid, Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Plato were being translated from Greek to Latin in the first half of the fourteenth century, and were therefore accessible to a wider audience, and a number of Byzantine and Greek scholars had arrived in Italy, bringing their science and

...more

Nature was the true teacher, and understanding this was key to understanding Nature herself. This idea is fundamental in Leonardo’s development as an artist and thinker and is many times repeated throughout his notebooks.

Considering Leonardo’s own wide-ranging curiosity, the workshop must have been an ideal place for his young mind to absorb the work surrounding him. Verrocchio’s most important engineering achievement was to create and install, in 1471, the ‘golden’ orb on top of the lantern of the dome of Florence Cathedral. The technical aspects of the project would have been complex and were recalled by Leonardo in a note he wrote some forty years later.

He would have been taught how to mix pigments and practise drawing from models, as well as taking part in the preparation of bronze sculpture and machinery for theatrical sets. He was also exposed to the practical and engineering aspects of completing larger projects.

A court appointment was in many ways an ideal position for Leonardo because it took away the pressure of depending upon commissioned work as would be necessary for an independent artist. Crucially, this gave him time to explore all of his interests while earning a steady salary.

It was during his stay in Milan when he was in his thirties and forties that he would begin his notebooks in earnest and mature and develop into a powerful thinker, bringing together Florence’s more Neoplatonic philosophy with a Milanese Aristotelian approach and adding his own belief systems surrounding his approach to man and nature. His intellectual development during this time was prodigious and seems to have exploded into an understanding of the underlying unity of nature through his development as a natural philosopher.

It is possible to trace his intellectual and practical developments in Milan through his notebooks, which began around 1485 with the drawings and notes in MS B (1485–8). This and other early notebooks are filled with architectural drawings, practical and fantastical military designs, and hydraulic studies in keeping with his work for the Sforza court.

Sometimes repetitive in content, they include extracts from other books, personal notes, and varied calculations.

Most of the notes are accompanied by drawings, diagrams, and visual observations. Words often serve to explain the images and images often illustrate an idea, demonstration, or experiment.

Leonardo was not fluent in Latin, a considerable disadvantage, as most of the philosophical and scientific texts were written in Latin. Whereas all men of letters and science were conversant in the language, Leonardo struggled with even a basic knowledge. The notebooks from Milan show that he was trying to teach himself so that he could read the texts first hand. He defended his inability to read original texts by attacking men of letters for relying on the writings of others rather than thinking for themselves. Leonardo cited experience which ‘has been the mistress of whoever has written

...more

It was experience that brought wisdom. Without it, there was no foundation. Although the Aristotelian idea of relying on nature was certainly known and understood in the Renaissance, Leonardo’s development of the idea and dogged adherence was his own. It begins to explain why we have thousands of sheets of notes and images investigating and reinvestigating the world around him.

Leonardo’s belief in experience was fundamental. However, his notebooks reveal that he was also researching the classical texts for the principles of nature—its laws—which could provide him with the criteria for investigating experience.

‘The painter’s work will have little merit if he takes for his guide other pictures, but if he will learn from natural things he will bear good fruit … those who take for their guide anything other than Nature—mistress of the masters—exhaust themselves in vain’

‘The youth should first learn perspective, then the proportions of objects, then he may copy from some good master, to accustom himself to fine forms. Then from nature, to confirm by practice the rules he has learned’

Light and shade were of extreme importance to Leonardo as they illuminated and gave description to the world around us and he devoted a great deal of time to studying them. Although artists in Italy were also studying these effects, Leonardo took them to a different level, devising formulas and rules for the effects of light and shade on surfaces and reapplying them to painting in a method known as chiaroscuro in order to acquire tonal qualities which would shape the entire structure of the composition.

Leonardo believed that an intense study of nature was what brought knowledge to the world. It was through our most important of the senses, the eye, that the world came into our brain, where it was interpreted and stored in the ‘sensus communis’ for the understanding of the soul. The soul’s primary role was to understand the workings of nature, not to concentrate on Neoplatonic thoughts of abstract speculation. Truth was not to be found in investigating the soul, but understanding the world.

‘The distance between the chin and the nose and that between the eyebrows and the beginning of the hair is equal to the height of the ear and is a third of the face’ (p. 141). His drawing known as the Vitruvian Man shows the proportional relationships of the human body within the geometry of a circle and square (p. 140).

‘Painted figures must be done in such a way that the spectators are able with ease to recognize through their attitudes the thoughts of their minds

No less entertaining and equally creative were the tales and fables Leonardo wrote. They display a deep and fertile imagination—what he termed fantasia. We know from his book lists that he owned chivalric romances, imaginative poetry, and collections of tales, fables, and jests.

Emotion as a fundamental element of narrative painting was something Leonardo wrote about in his notes for the proposed treatise on painting: ‘That which is included in narrative paintings ought to move those who behold and admire them in the same way as the protagonist of the narrative is moved’

One of the challenges Leonardo set himself was the possibility of man achieving flight. This would be the greatest engineering achievement of all. Leonardo spent a great deal of time studying the flight of birds and the possibility of man flying, or as he eventually realized, gliding. In the early 1490s, when he was still in Milan, his notebooks show he was working on a flying machine, which he drew suspended from his studio ceiling and noted a plan to test the machine secretly.

It seems clear from his notebooks that Leonardo was attempting to outline an underlying science for all things. He sought its rules by finding the shared principles behind the varied phenomena of nature he investigated. However, he could not stop at the principles. He had a need to go beyond this to find all the variations he observed based on a multitude of effects. All details and variations in nature needed to be fully described, and understood. Only when every possible cause and effect had been studied could one come to a true understanding of how nature worked.

Throughout his writings one sees variations on a recurring note: ‘Tell me if anything was ever done?’ as if in the middle of one of his investigations he was aware that he could question a thing indefinitely. That he was unable to cease in his quest, the thousands of sheets that make up his notebooks testify. They are witness to an unerring commitment to knowledge, and no other body of writing equals their range in exploring man and the world around him.

Leonardo’s view of what science should be foreshadows the critical and constructive methods of modern times. He proceeded step by step. (1) Experience of the world around us as gained through the senses is taken as the starting-point. (2) Reason and contemplation, which, though linked to the senses, stands above and outside them, deduces eternal and general laws from transitory and particular experiences. (3) These general laws must be demonstrated in logical sequence like mathematical propositions, and finally (4) they must be tested and verified by experiment, and then applied to the

...more

Consider now, O reader! what trust can we place in the ancients, who tried to define what the Soul and Life are—which are beyond proof—whereas those things which can at any time be clearly known and proved by experience remained for many centuries unknown or falsely understood.

Of what use, then, is he who in order to abridge the part of the things of which he professes to give complete information leaves out the greater part of the things of which the whole is composed. True it is that impatience, the mother of folly, is she who praises brevity, as if such persons had not life long enough to acquire a complete knowledge of one single subject, such as the human body. And then they want to comprehend the mind of God which embraces the whole universe, weighing and mincing it into infinite parts as if they had dissected it. O human stupidity! do you not perceive that

...more

All our knowledge has its origin in our perceptions.

The eye, which is called the window of the soul, is the chief means whereby the understanding may most fully and abundantly appreciate the infinite works of nature.

Experience never errs; it is only your judgement that errs in promising itself results as are not...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Experience does not err, it is only your judgement that errs in expecting from her what is not in her power.

All true sciences are the result of Experience which has passed through our senses, thus silencing the tongues of litigants. Experience does not feed investigators on dreams, but always proceeds from accurately determined first principles, step by step in true sequences to the end; as can be seen in the elements of mathematics.

Beware of the teaching of these speculators, because their reasoning is not confirmed by Experience.

The senses are of the earth; reason stands apart from them in contemplation.

Wisdom is the daughter of experience.*

Experience, the interpreter between formative nature and the human species, teaches that that which this nature works among mortals constrained by necessity cannot operate in any other way than that in...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Nature does not break her law; nature is constrained by the logical necessity of her law which is inherent in her.

Necessity is the mistress and guide of nature. Necessity is the theme and inventor of nature, its eternal curb and law.

Nature is full of infinite causes that have never occur...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

In nature there is no effect without cause; understand the cause and you will have n...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Whoever condemns the supreme certainty of mathematics feeds on confusion, and can never silence the contradictions of the sophistical sciences, which lead to an eternal quackery.

Science is an investigation by the mind which begins with the ultimate origin of a subject beyond which nothing in nature can be found to form part of the subject.

Nature is concerned with the production of elementary things. But man from these elementary things produces an infinite number of compounds; although he is unable to create any element except another life like himself—that is, in his children.

No created thing is more enduring than this gold. It is immune from destruction by fire, which has power over all other created things, reducing them to ashes, glass, or smoke. And if gross avarice must drive you into such error, why do you not go to the mines where Nature produces such gold, and there become her disciple? She will in faith cure you of your folly, showing you that nothing which you use in your furnace will be among any of the things which she uses in order to produce this gold. Here there is no quicksilver, no sulphur of any kind, no fire nor other heat than that of Nature

...more