More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

April 4 - May 1, 2020

Throughout the 1970s and 80s the United States fanned the civil wars of Central America, supporting repressive governments, devastating those countries, and helping to create cultures of violence, all in the name of defeating communism—with a promise to nurture just, democratic societies once peace was attained. There was no nurturing, no rebuilding, and even after the wars were over, there was no peace. The United States mostly turned its back, and now it spurns the offspring who flee what it created in Central America.

And what is cutting-edge journalism? It means writing about what nobody else dares to write about, at least not thoroughly or memorably,

Death isn’t simple in El Salvador. It’s like a sea: you’re subject to its depths, its creatures, its darkness. Was it the cold that did it, the waves, a shark? A drunk, a gangster, a witch? They didn’t have a clue.

He was telling me why he was running, and he kept stressing, again and again, that he had to run, that he had no other choice, that for some people in this world there are not two or three different choices. There is only one. Which is, simply, to run.

Violence, as Saúl well knows, can come from your own blood. Violence, as Olga Isolina says, can thrust you into depression. Violence, as the Alfaro brothers know, can terrorize you, especially when it has no face.

The difference between fleeing and migrating is becoming clearer to me. Fleeing takes speed. The boys know how to flee. Migrating, though, takes strategy, which the brothers don’t have.

Every day while en route to El Norte I saw, and began to understand, that the bodies left here are innumerable, and that rape is only one of the countless threats a migrant confronts.

For years undocumented migrants have considered robberies and assaults as the inevitable tolls of the road. God’s will be done, they repeated. The coyotes even started to hand out condoms to their female clients, while they recommended the men not resist an attack. For the past decade, in this hidden and forgotten part of Mexico, the stories of husbands, sons, and daughters watching women suffer abuses have been commonplace.

Tomorrow we’ll go to the police station responsible for patrolling this sector for the past three months. And we’ll remain locked into this paradox, easily traveling around the dangerous Arrocera without even a whiff of the fear that migrants breathe daily.

Vultures continuously circle the area, looking for dead cattle and dead people. Bones here aren’t a metaphor for what’s past, but for what’s coming.

We’re walking among the dead. Life’s value seems reduced, continuously dangled like bait on a fishing line. Killing, dying, raping, or getting raped—the dimensions of these horrors are diminished to points of geography. Here on this rock, they rape. There by that bush, they kill.

“He’s going to talk because it’s not like he’s accused of a serious crime. We don’t have anyone accused of serious crimes here. They’re accused of murder, rape, or robbery. Never of drug trafficking.”

We walk on, telling ourselves that if we get attacked, we get attacked. There’s nothing we can do. The suffering that migrants endure on the trail doesn’t heal quickly. Migrants don’t just die, they’re not just maimed or shot or hacked to death. The scars of their journey don’t only mark their bodies, they run deeper than that. Living in such fear leaves something inside them, a trace and a swelling that grabs hold of their thoughts and cycles through their heads over and over. It takes at least a month of travel to reach Mexico’s northern border. A month of hiding in fear, with the

...more

Few think about the trauma endured by the thousands of Central American women who have been raped here. Who takes care of them? Who works to heal their wounds?

Migrants who are women have to play a certain role in front of their attackers, in front of the coyote and even in front of their own group of migrants, and during the whole journey they’re under the pressure of assuming this role: I know it’s going to happen to me, but I can’t help but hope that it doesn’t.” Migrant women play the role of second-class citizens. And they are an easy target. That was made very clear to us a couple days ago when we visited the migration offices of Tapachula and spoke with Yolanda Reyes, a twenty-eight-year-old who has lived here illegally since 1999. She made a

...more

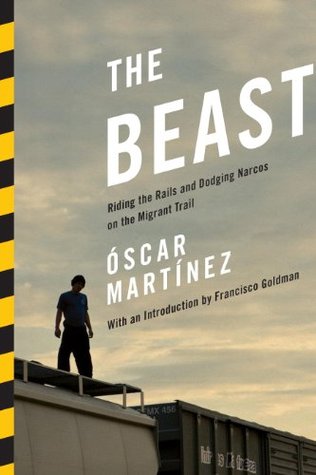

These are the migrants riding third class, those without either a coyote or money for a bus. The men repeat this fact over and over. They will be sleeping alongside these rails for the bulk of the trip across Mexico, hoping that as they rest they won’t miss the next whistle and have to wait as long as three days for another train. They’ll travel in these conditions for over 3,000 miles. This is The Beast, the snake, the machine, the monster. These trains are full of legends and their history is soaked with blood. Some of the more superstitious migrants say that The Beast is the devil’s

...more

Father Solalinde put it well: this land is a cemetery for the nameless.

The prostitutes in this region often refer to working one of the bars with the self-reflexive term, me ocupé, meaning, literally, I occupied myself, I employed myself. They speak as if they were two, as if one of their selves managed the other, as if the body that had sex with the men was a puppet that they themselves only temporarily occupied or employed.

Sitting on the curb of a dirt road, weeping just outside of Calipso, Erika paints a typical portrait of the Central American migrants whose suffering lights up the nights of these border towns. Many of the women have no previous schooling. They flee from a past of severe family dysfunction, physical and sexual abuse, and they often come to these brothels as girls, little girls, incapable of distinguishing between what is and what should be. They’re fresh powder, ready to be packed into the barrel of a gun.

“If you’re not from the social reality of our countries, you’re not going to understand,”

At a certain level, they know they’re victims, but they don’t feel that way. Their logic runs like this: yes, this is happening to me, but I took the chance, I knew it would happen.”

There is, as Flores says, an expression for the transformation of the migrant’s body: cuerpomátic. The body becomes a credit card, a new platinum-edition “bodymatic” which buys you a little safety, a little bit of cash and the assurance that your travel buddies won’t get killed. Your bodymatic, except for what you get charged, buys a more comfortable ride on the train.

These are the kidnappings that don’t matter. These are the victims who don’t report the crimes they suffer. The Mexican government registered 650 kidnappings in the year 2008, for example. But this number reflected only reported cases. Time spent on the actual migrant routes proves that such numbers are a gross understatement.

There is, simply put, nobody to assure the safety of migrants in Mexico. Sometimes a week or more will pass before a migrant on the trail will have the chance or the money to call a family member. Migrants try to travel the paths with the fewest authorities and, for fear of deportation, almost never report a crime. A migrant passing through Mexico is like a wounded cat slinking through a dog kennel: he wants to get out as quickly and quietly as he can.

Which makes me think that the money wiring companies must know [based on the number of wires a single person receives] who they’re dealing with. We have trustworthy reports that municipal police have detained migrants and handed them over to the kidnappers.”

Meanwhile, just down the street from these same offices, the kidnappings continue. It’s so well-known, I figure, that there’s no way that if I finally did get an official on the phone they’d be able to answer me without a resounding yes. And with that yes they would be admitting that migrants are being systematically kidnapped just outside of their offices. Which is why, I figure, they don’t pick up their phones.

The upspoken question becomes evident. How is it possible that the kidnappings are still happening when the local governments, the countries of origin, the media, the Mexican government, and the US government all know exactly what’s going on?

What Consul Ortiz says is clear: everybody knows, nobody acts, and the kidnappings continue.

They’re not gangs and they’re not corner hoodlums. They’re organizations that cross hundreds of tons of South American cocaine and Mexican marijuana and methamphetamine to the United States.

“Let us ask God to forgive the politicians who created these walls,” Armando Ochoa, a bishop from El Paso, says in prayer.

“We’d have a row that reached to the sea if we wanted to put up a cross for every death in the desert,” says Bishop Renato León in his sermon.

There are no absolute numbers here. Each institution or expert has their own estimate. No one tallies by area, nationality, gender, or age. The dead are dead. Dead in the desert, the rivers, the hills. Dead migrants.

The argument this Honduran makes is that Juárez is simply not the crossing zone it used to be. It’s not a place for migrants anymore. It’s a cartel war zone, which in turn has increased US border vigilance. One thing leads to another—violence and then vigilance—and the migrants bear the brunt of both.

Few migrants arrive having studied the landscape. They play a game of chance, clutching to the roof of a train that will take them to some new and unknown destination. Still, Rubio thinks there’s a vox populi on the migrant route that tells many which course to follow. Not an exact route, but a vague knowledge of where it’s best not to try. It’s the voice of the coyotes, who sprinkle some of their knowledge as they move northward. They know, not from official documents, but from living in the desert, in the hills and along the Rio Bravo, where there’s more surveillance, more Border Patrol

...more

I write this scene to explain something to the reader: undocumented migration to the United States will not stop. Or, it’s safe to say, neither the reader nor I will see a time when it will stop. Undocumented migration to the United States may fluctuate depending on the year, but like a river it continues, ebbing and flowing, always finding its way to the sea.

I could give you more facts, but for me the image of a mutilated man leaning on his crutches is a lot more powerful than any sum or number.

the Mexican government, watching it all with a disinterested gaze that tells us that not all humans are worth the effort, that there are some we protect and others we let suffer and die. That there are some people who are important and others who are not. It’s that simple. And beyond Mexico, protecting the land of abundance and prosperity, there is the border, the wall, the sensors, the helicopters, the Border Patrol, the desert, and the Rio Grande. The Central American journey toward the false promised land is like climbing the slopes of Everest: the higher you get the less air there is to

...more

And now that I think about it, now that the book has been translated into English, I realize I never asked these courageous travelers an equally important question: Where do you think you’re going? I don’t mean what their next step will be on the tortuous migrant paths, as it’s clear that very few have any idea. I remember speaking to a few undocumented migrants on the border between Arizona and Sonora who were surprised to hear me explain that there was an entire desert still ahead of them.

Their life trajectory is pointed solely at the US, just like it was for their parents and for their grandparents. And those who set out on this heroic journey are often reluctant to tell their families that they were raped, kidnapped, robbed, and beaten along the way. Migrants are silent, guarded. And silent not just about the voyage, but also about life in the US.

In my few trips to the US I spoke with many undocumented migrants and various leaders of Latin American communities. Though their stories of success inspire the courage for many others to take the journey, most of the stories I heard were of hardship, of brutal working conditions, of fear, of secret lives marked by the constant possibility of deportation, of the humiliation suffered because of the threats from and scorn showed them by some American citizens. Traveling with migrants throughout Mexico and in some parts of the US, I couldn’t help but see this trip as beginning badly, getting

...more

I don’t think compassion is that useful. I don’t think it’s a durable engine for change. I see it as a passing sentiment, a feeling too easy to forget. In Mexico, every time we presented the Spanish version of this book I’d say to the audience that my goal was to incite rage. Rage is harder to forget. Rage is less comfortable than compassion, and so more useful. Rage and indignation, these were my objectives in Mexico. Now I consider what feelings I hope to incite in an American reader. I’m not hoping readers will feel compassion for the men and women who go through this hellish trial in order

...more