More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

March 5 - March 13, 2022

Apparently this remote countryside wasn’t always populated by murderers, robbers and rapists. What happened was that when the Mexicans living there noticed the migrants crossing their lands, so vulnerable, so frightened of ever denouncing any crime committed against them for fear of being deported, so determined only to reach their destination, their predatory instincts were awakened, and they adapted to what this new situation offered. The Beast offers a terrifying lesson in human cruelty, cowardice, greed and depravity.

Migrants who are women have to play a certain role in front of their attackers, in front of the coyote and even in front of their own group of migrants, and during the whole journey they’re under the pressure of assuming this role: I know it’s going to happen to me, but I can’t help but hope that it doesn’t.

There’s an expression among the women migrants: “cuerpomátic. The body becomes a credit card, a new platinum-edition ‘bodymatic’ which buys you a little safety, a little bit of cash and the assurance that your travel buddies won’t get killed.

“This is the law of The Beast that Saúl knows so well. There are only three options: give up, kill, or die.”

Now and then an especially large massacre, like that of seventy-three migrants in Tamaulipas in 2011, brings some media focus, but it passes all too quickly. Catholic Church leaders such as the priest Alejandro Solalinde in Oaxaca have been at the forefront of efforts to force Mexican authorities to provide better protection for migrants. Of the many silences that overlay this story, one of the most profound is that of the United States, where the tragedy of the migrants is what news editors call a “non-story,” one to which Washington could not be more indifferent.

Throughout the 1970s and 80s the United States fanned the civil wars of Central America, supporting repressive governments, devastating those countries, and helping to create cultures of violence, all in the name of defeating communism—with a promise to nurture just, democratic societies once peace was attained. There was no nurturing, no rebuilding, and even after the wars were over, there was no peace. The United States mostly turned its back, and now it spurns the offspring who flee what it created in Central America.

Though the dream is easy, the voyage is incredibly dangerous. Sometimes it’s simply the exhaustion that kills you. Sometimes it’s just one slow moment of slipping into sleep, and your head is gone from your body.

Death isn’t simple in El Salvador. It’s like a sea: you’re subject to its depths, its creatures, its darkness. Was it the cold that did it, the waves, a shark? A drunk, a gangster, a witch? They didn’t have a clue.

Because poverty and death touches them all: the young and the old, the men and the women, the gangsters and the cops.

Pride and violence, she had learned, are never a good mix.

Violence, as Saúl well knows, can come from your own blood. Violence, as Olga Isolina says, can thrust you into depression. Violence, as the Alfaro brothers know, can terrorize you, especially when it has no face.

The difference between fleeing and migrating is becoming clearer to me. Fleeing takes speed. The boys know how to flee. Migrating, though, takes strategy, which the brothers don’t have.

Bones here aren’t a metaphor for what’s past, but for what’s coming.

We’re walking among the dead. Life’s value seems reduced, continuously dangled like bait on a fishing line. Killing, dying, raping, or getting raped—the dimensions of these horrors are diminished to points of geography. Here on this rock, they rape. There by that bush, they kill.

tell him I’m going on with Eduardo, José and Marlon to Arriaga, where we’ll catch the next train. The officers shoot me a worried look. I imagine they think of that colleague of theirs who was recently murdered. I imagine that, for them, a dead migrant is commonplace, but a couple of dead journalists is another matter. No one wants those kinds of bodies—the ones that come with names—found in their jurisdiction.

“He’s going to talk because it’s not like he’s accused of a serious crime. We don’t have anyone accused of serious crimes here. They’re accused of murder, rape, or robbery. Never of drug trafficking.”

“There’s not just one guy working these trails. There are gangs. And not just one gang. Which means there’s never a pause. If somebody falls, someone takes their place right away. It’s a lot of land, and it’s remote, and maybe the law does go chasing the bandits. But the bandits who work it, they know the law too, they keep their eyes open, and they know the land even better than they know the law. The law just can’t cover it. The place is too big. And if the law does run into the bandits, the bandits will shut it down. They have .22 shotguns, AR-15s, 357s. They even have bulletproof vests.”

La Arrocera is something else. Bandits are better equipped there than cops. El Calambres assures us that gangs consider migrants as part of their long-term business

We walk on, telling ourselves that if we get attacked, we get attacked. There’s nothing we can do. The suffering that migrants endure on the trail doesn’t heal quickly. Migrants don’t just die, they’re not just maimed or shot or hacked to death. The scars of their journey don’t only mark their bodies, they run deeper than that. Living in such fear leaves something inside them, a trace and a swelling that grabs hold of their thoughts and cycles through their heads over and over.

It takes at least a month of travel to reach Mexico’s northern border. A month of hiding in fear, with the uncertainty of not knowing if the next step will be the wrong step, of not knowing if the Migra will turn up, if an attacker will pop out, if a narco-hired rapist will demand his daily fuck.

Migrant women play the role of second-class citizens. And they are an easy target.

“Whore, you fucking whore, you’re going to learn, you’re just a fucking Central American and you’re not worth a thing!” Those are the words she remembers.

He recommended this route in particular, he said, because it had one clear advantage—it stayed close to the highway, which meant potential help, which meant people would be able to hear our screams. It sounded terrifying.

one woman, a twenty-year-old pregnant Honduran who had been raped in La Arrocera two days ago. She said it was the people she traveled with who raped her. They’d told her they were migrants and convinced her to walk with them. Then all three of them raped her. When her son aborted between her legs, the bandits killed him with blows. Then they beat the woman until she lost consciousness. When she came to, she was completely alone. As well as she could, still bleeding, she managed to walk to the highway for help.

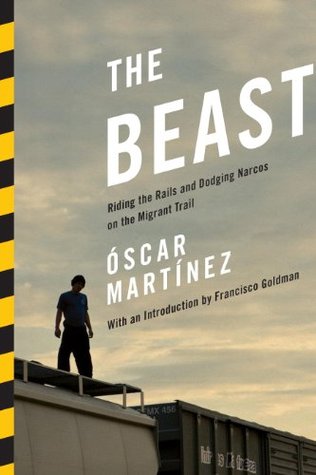

The whistle blows long and loud in the darkness. The Beast is coming. One blow. Two blows. The shrill call of the rails. Time to get moving. Tonight there are a hundred or so of them. They wake, shake off their sleep, heft packs onto their shoulders, grab their water bottles, and start onto the path of death.

It’s a sensation between the excitement of the ride and the fear of the uncertainty.

Why don’t they let them board before the train starts moving? Why, if they know that the migrants are going to get on anyway, do they make them jump on while it’s already chugging? It’s a question that none of the directors of the seven railroad companies is willing to answer. They simply don’t give interviews, and if you manage to get them on the phone, they hang up as soon as they realize you want to talk about migrants.

This is The Beast, the snake, the machine, the monster. These trains are full of legends and their history is soaked with blood. Some of the more superstitious migrants say that The Beast is the devil’s invention.

Others say that the train’s squeaks and creaks are the cries of those who lost their life under its wheels. Steel against steel.

“The Beast is the Rio Grande’s first cousin. They both flow with the same Central American blood.”

But before reaching the goal there is the journey to face, a journey that can take even more from you than what you’re looking to make.

This is the law of The Beast that Saúl knows so well. There are only three options: give up, kill, or die.

Father Solalinde put it well: this land is a cemetery for the nameless.

The word sex means rape. The word family refers to a fellow victim. And a body is little more than a ticket from one hell to another hell. It’s called “The Trade”: thousands of female Central American migrants, far from their American Dreams, trapped in prostitution rings in Southern Mexico.

What many of them won’t tell you is that they knew they’d be raped on this journey, that they feel it’s a sort of tax that must be paid.

They travel with that lodged in their minds, knowing that they’ll be abused once, twice, three times … Sexual abuse has lost its terror.

At a certain level, they know they’re victims, but they don’t feel that way. Their logic runs like this: yes, this is happening to me, but I took the chance, I knew it would happen.”

it’s hard to tell what pieces of her story are directly autobiographical. It’s as though the horrors of their lives were shared by all, as though what happened to one them has inevitably happened to all of them.

This rationalization is commonly used as justification—those who let themselves be exploited have only themselves to blame. But, as Flores explains, such passive victims are young girls with no education, who don’t know how to condemn or report anything that happens to them, who are easy to intimidate. If you try to escape, I’ll call Migration and they’ll get hold of you real fast! “It’s a problem of submissiveness,”

The journey is hard; tender moments are rare. Those recruiting fresh bodies to work in the brothels are the same Central American women who, against their will, were tricked into prostitution and now, years later, are offered extra pay to trick other newly arrived girls by making them the same false promises they once heard: you’ll become a waitress, you’ll be well paid.

So, regarding Prosecutor Tamayo’s statement about the impossibility of identifying cartels, it must be said that there is a big difference between wanting to know and being able to know. Between trying and being too scared to try.

street. They come from circumstances that encourage the normalization of prostitution, rape, and human trafficking. It’s a reality in which kids die by the dozen, fathers are aggressors, and neighborhoods are war zones.

it’s not uncommon that a migration official abuses a woman in custody. Who is going to report a human trafficking violation to an agent who has offered you freedom in exchange for sex? And the abuse doesn’t end there. As a trafficking prosecutor explained to me, the National Institute of Migration often plays a leading role in preventing human trafficking victim testimonies from getting a court hearing.

These are the kidnappings that don’t matter. These are the victims who don’t report the crimes they suffer. The Mexican government registered 650 kidnappings in the year 2008, for example. But this number reflected only reported cases. Time spent on the actual migrant routes proves that such numbers are a gross understatement.

There is, simply put, nobody to assure the safety of migrants in Mexico. Sometimes a week or more will pass before a migrant on the trail will have the chance or the money to call a family member. Migrants try to travel the paths with the fewest authorities and, for fear of deportation, almost never report a crime. A migrant passing through Mexico is like a wounded cat slinking through a dog kennel: he wants to get out as quickly and quietly as he can.

Their secret is simply fear. They shake the bones of policemen and taxi drivers, lawyers and migrants. All you need to do to get someone to dance the dance of fear is to utter the famous, simple motto: we are Los Zetas.

Los Zetas are like a metastasizing cancer. Migrants are recruited. Soldiers are recruited. Policemen, mayors, businessmen—they’re all liable to become part of the web.

They live to push the limits, working under constant risk, repeating over and again this lethal journey. They are coyotes, polleros, the pirates of the migrant trails. They live in a world they don’t control, taking orders from narcos, those who run the migrant trails in this country.

And we began to understand that even a border this long doesn’t have space enough for everyone, much less for those who are last in line.

It’s a game of chance, this border. Sometimes you get lucky and sometimes you don’t.