More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

October 12 - October 31, 2022

On the migrant roads there are wolves and there are sheep. The three brothers, bumbling naively through the square, look nothing like wolves. They don’t even prepare themselves in case the father’s friend turns out to be a coyote. They don’t think about how they’ll try to negotiate to avoid the undeclared taxes and extra charges. If a coyote knows he’s working with fresh meat, he’s going to try to squeeze them dry. Auner

I keep sending messages, but get no replies. I read about the massive kidnapping in Reynosa. At least thirty-five Central Americans, all riding the rails, all captured by Los Zetas. Where are you? How are you? Nothing. No response.

The Mara Salvatruchas gang originated in Los Angeles in the 1980s, but it has since become a transnational organized crime gang, with its largest presence in Central America and southern Mexico.

most dangerous part of the migrant trail through Mexico, where undocumented Central Americans have no protection and where the horrors seem ceaseless and locals seem deaf to screams, is La Arrocera.

trails, I’ve heard the stories of hundreds of attacks, of people beaten to a pulp, of murder, of women screaming while they were raped in those hills, and, just beyond them, Mexico refused to listen.

Paola, a twenty-three-year-old transsexual Guatemalan, says that she expected to be attacked while traveling. “I’d been told this always happens to migrants,” she ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

What she does confess to acquiring, after five years of prostituting herself in Guatemala and Mexico City, is a life-saving resource around perverted men: the combination of wits and will.

Paola is a true survivor of La Arrocera.

La Arrocera is a network of twenty-eight ranches scattered among thick overgrowth that stretches between Tapachula, the first big city one comes to on the migrant trail through Mexico, and the coastal city of Arriaga, which all migrants must reach to catch the train. At the end of this line of ranches lies a large, abandoned rice cellar, which gives the place its name. La Arrocera means, simply, The Rice Cellar. Paola saw firsthand that something bad happens to nearly every migrant here. La Arrocera is lawless territory.

Many of the victims are never found. It’s not uncommon that migrants travel alone, without identification and

At the time of her rape and murder there wasn’t a police force dedicated to these rural areas, and really it’s a sorry sight now that there is—seven men from the nearby towns, standing guard with clubs in hand whenever they have some free time.

The stories are all that’s left.

At the beginning of 2009, the government of the state of Chiapas finally started paying attention to the violence on these trails.

And then one day one of the laborers must have got an idea: the migrants are walking these trails in order to hide from the authorities, so if there were to be an assault, a rape, say, or a robbery, nobody would report it.

At the beginning of 2009, after more than a decade of petitions from human rights organizations, the Chiapan government finally bowed to the pressure. A visit from the chancellors of Guatemala and El Salvador and a letter signed by more than ten organizations, including the Catholic Church, prevailed on the government to take the first steps: creating the Prosecutor’s Office for Migrants and convincing Governor Juan Sabines to order police chiefs in Huixtla and Tonalá to start patrolling the most dangerous portions of the migrant trails. In the end, though, they’ve just barely stirred the pot

...more

“Operation Friend.”

“It’s even worse in La Arrocera,” he says. “There the bandits are organized and carry AR-15s. We only go in when we’ve thoroughly detailed an operation first.”

the victims here are only written about once they are dead.

the only people who really know what goes on in La Arrocera are the migrants and the bandits themselves. These mountains, there’s no better way to say it, have their own laws.

Chayote, he says, a famous local bandit who was detained four months ago, was released because his victims kept on their northern march instead of testifying. Chayote, we learn, actually turned himself in, opting to spend a few years in prison rather than get stoned by defensive migrants under one of the bridges in La Arrocera.

In Chiapas most denunciations filed by migrants are against the police. A migrant putting himself in police custody is about the same as a soldier asking for a sip of water at enemy headquarters.

Eduardo, we learn, is a twenty-eight-year-old baker who’s fleeing the Mara Salvatruchas. Marlon is a twenty-year-old distributor who loyally sticks with Eduardo, his boss.

He waves to us and the officers wave back. It’s a casual, everyday gesture. “And them?” I ask the officer next to me. “They’re your friends?” “Spies,” he answers dryly. “They work with the bandits. They’re the ones who push the migrants off trail and to the spot where the gangs wait to attack them. Every time we do our rounds, they’re out here, watching us.”

It was here last year that an officer, one of his colleagues, was killed. A bandit broke his skull with a machete. A newly sharpened machete is, for these outlaws, more weapon than tool. They use it to break up soil, sure, but mostly to attack, or to defend themselves. The officers say the bandits always have a machete, their most loyal companion, in hand, as if it were a natural extension of their arms.

Bones here aren’t a metaphor for what’s past, but for what’s coming.

We’re walking among the dead. Life’s value seems reduced, continuously dangled like bait on a fishing line. Killing, dying, raping, or getting raped—the dimensions of these horrors are diminished to points of geography. Here on this rock, they rape. There by that bush, they kill.

After our guided tour through La Arrocera it’s clear to me that every attempt to eradicate violence in this area has been haphazard and unsuccessful.

A CHAT WITH EL CALAMBRES

He was initially charged for rape, arms smuggling, and assault. He was accused of having raped a migrant, but, not surprisingly, the accuser disappeared. The other two charges stuck. And now he’s waiting out his prison sentence.

The prison director offers his office for the interview and says that Higinio will probably talk. His reasoning is disturbing, but also not surprising: “He’s going to talk because it’s not like he’s accused of a serious crime. We don’t have anyone accused of serious crimes here...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

El Calambres is thin, with sharp features and veiny arms. He wears an oversized shirt which, coupled with his rural mannerisms, gives him the look of a gangster. He’s five foot five and has long sharp fingernails, slanted eyes and a thin, lopsided mustache. Six chains hang around his neck, all crucifixes and rosaries.

They would always be fucking with anyone passing by.” “Who would be fucking with them?” “The people who lived and worked there. I’ve seen the gangs that come through. Now there’s just one of them around. They came up from Tapachula to do their business. El Chino runs the operation. The other boss is El Harry. They’ve been around a while now, doing their thing, hunting illegals.” “And why do they only hunt the undocumented?” “Because they know those people aren’t going to stick around and cause trouble. If they mess with someone who’s from here, though, they know they’re going to have problems,

...more

El Chino is still working. Everyone knows him by his nickname, and considers him one of the biggest bandits of La Arrocera. El Harry is even more legendary. He’s one of the first who capitalized on the impunity in this area, one of the first who started with the robberies and rapes.

From inside, El Chochero and El Diablo continue to run their narco operations, putting taxes on new inmates and keeping guards out of their cells.

How much can you make assaulting migrants?” “Depends on how much the migrants are carrying. Some carry ten pesos, others carry five or even eight thousand pesos. See,” he says, “they’re not just fucking with them in the hills here. They start fucking with them way down south so that by the time they get here some of them are already broke.” “And how’s business? If I were to grab a machete and just try my luck?” “Nooo, it’s all under control. Each group has its turf. Nobody can operate on somebody else’s turf. If you just show up, you’ll get shot.” “And if you stand up to the gangs, is that a

...more

“There’s not just one guy working these trails. There are gangs. And not just one gang. Which means there’s never a pause. If somebody falls, someone takes their place right away. It’s a lot of land, and it’s remote, and maybe the law does go chasing the bandits. But the bandits who work it, they know the law too, they keep their eyes open, and they know the land even better than they know the law. The law just can’t cover it. The place is too big. And if the law does run into the bandits, the bandits will shut it down. They have .22 shotguns, AR-15s, 357s. They even have bulletproof vests.”

...more

gangs consider migrants as part of their long-term business plan, though sometimes, “thanks to some connections,” they stumble upon other jobs: robbing jewelry stores, cars, businesses. And no gang works alone: they have authorities that are in the game with them.

The suffering that migrants endure on the trail doesn’t heal quickly. Migrants don’t just die, they’re not just maimed or shot or hacked to death. The scars of their journey don’t only mark their bodies, they run deeper than that. Living in such fear leaves something inside them, a trace and a swelling that grabs hold of their thoughts and cycles through their heads over and over.

It takes at least a month of travel to reach Mexico’s northern border.

Migrants who are women have to play a certain role in front of their attackers, in front of the coyote and even in front of their own group of migrants, and during the whole journey they’re under the pressure of assuming this role: I know it’s going to happen to me, but I can’t help but hope that it doesn’t.”

Migrant women play the role of second-class citizens. And they are an easy target. That was made very clear to us a couple days ago when we visited the migration offices of Tapachula and spoke with Yolanda Reyes, a twenty-eight-year-old who has lived here illegally since 1999. She made a life for herself in Tapachula and tried to live normally, but, even after so many years, something wouldn’t ease her mind: she was still an undocumented Central American woman. She’d just gotten legal residency the day we met her, after a long process of filing a complaint against her partner, a Chiapan police

...more

He recommended this route in particular, he said, because it had one clear advantage—it stayed close to the highway, which meant potential help, which meant people would be able to hear our screams. It sounded terrifying.

Then we get off in time to board another en route to Tonalá. We’re told the checkpoint there is highly militarized, but that the officers are only worried about arms and drugs smuggling, and we’re promised they won’t ask for any documents.

This time, in all that immensity that is La Arrocera, there was no attack. Maybe it is calm, maybe the story here in Chiapas has changed course, maybe the prosecutors, police officers, and lawmakers are successfully reaching their goal.

Carlos Bartolo, who runs the migrant shelter in Arriaga, tells me that just today four people who’d been robbed showed up. One of these, Ernesto Vargas, a twenty-four-year-old from a small Salvadoran town called Atiquizaya, was robbed by two men, one who carried a machete and another who held a .38 revolver pointed at his chest. They took everything he had: $25 and 200 pesos. I call Commander Maximino, who says he’s checking into it. It seems, he tells me, that a group of bandits have moved a few miles to the north, to the border of Oaxaca, where they’ve set up a safe house in the mountains.

...more

I call the priest Alejandro Solalinde, who is in charge of the shelter in Ixtepec, Oaxaca, where the train—The Beast—drops off the migrants who are riding from Arriaga. Solalinde tells me that after eight months without incident, the train that arrived that very morning was attacked. Some bandits armed with pistols and machetes jumped on board at the Oaxaca–Chiapas border and stripped all the travelers.

Three more Salvadorans were robbed in Huixtla, including one woman, a twenty-year-old pregnant Honduran who had been raped in La Arrocera two days ago. She said it was the people she traveled with who raped her. They’d told her they were migrants and convinced her to walk with them. Then all three of them raped her. When her son aborted between her legs, the bandits killed him with blows. Then they beat the woman until she lost consciousness. When she came to, she was completely alone. As well as she could, still bleeding, she managed to walk to the highway for help.

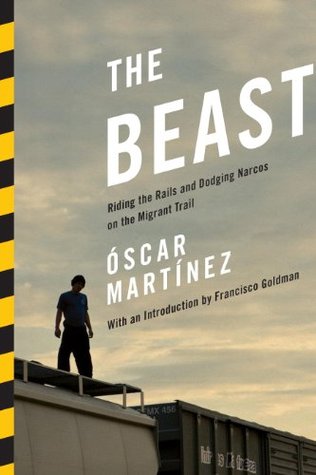

The train is a long series of uncertainties. Which cars are going to be leaving? Which one will take you to Medias Aguas and which to Arriaga? How soon will it leave? How will you duck any rail workers? To avoid an assault, is it better to ride the middle or the back cars? What sounds signal you to jump on? When do you get off? What happens when you need to sleep? Where is the best place to tie yourself to the roof? How do you know if an ambush is coming?

Why don’t they let them board before the train starts moving? Why, if they know that the migrants are going to get on anyway, do they make them jump on while it’s already chugging? It’s a question that none of the directors of the seven railroad companies is willing to answer. They simply don’t give interviews, and if you manage to get them on the phone, they hang up as soon as they realize you want to talk about migrants.

Some of the more superstitious migrants say that The Beast is the devil’s invention. Others say that the train’s squeaks and creaks are the cries of those who lost their life under its wheels. Steel against steel.