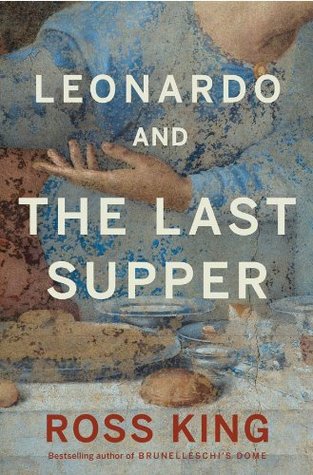

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

The authors of the four Gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—each provided his own narrative. As with other episodes in the life of Christ, there are strong parallels in the first three accounts, whose works are known as the synoptic Gospels. They include many of the same events, often told in the same order and with similar phrasing—resemblances that lead scholars to believe they were composed interdependently. Although differences exist between and among the authors of the synoptic Gospels on specific details of the Last Supper, Matthew, Mark, and Luke are more in accord with one another

...more

The two eyewitnesses who wrote accounts of the Last Supper were Matthew and John. Matthew’s was consistently regarded as the earliest of the four Gospels, hence its position at the beginning of the New Testament. Matthew was one of the select group of followers known as the apostles: the twelve men whom Christ, after climbing a mountain in Syria, called to a special mission to preach with him. “And he gave them power to heal sicknesses,” reports the Gospel of Mark, “and to cast out devils” (Mark 3:15). The apostles were present during Christ’s triumphant entrance into Jerusalem on the back of

...more

In the synoptic Gospels, accounts of the Last Supper begin immediately after Judas goes to the high priest and strikes the deal to betray Christ, whose powers the priests and the Pharisees resent and fear.2 Matthew alone enumerates Judas’s fee as thirty pieces of silver, with Mark and Luke merely noting that the high priest and his cronies agreed to give him an unspecified sum. John, on the other hand, makes n...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Passover is approaching: the festival in which the Jews ritually slaughter and eat a male lamb to commemorate their deliverance from the avenging angel and their liberation from captivity in Egypt. The apostles ask Christ where they should prepare for the feast. According to Matthew, Christ instructs them to locate “a certain man” in the street in Jerusalem and say to him: “The master says, My time is near at hand.” Mark and Luke add the detail that this stranger can be recognized because he will be carrying a pitcher of water. “Follow him,” Mark reports Christ as telling them. “And wherever

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

When evening falls, Christ sups with his apostles inside this large dining room. The supper takes place either on the feast of the Passover or, in John’s account, during preparations for it (he makes clear that the meal is prior to the actual festival). In any case, the Crucifixion that follows is symbolically linked—especially in Luke and John—to the slaughter of lambs for the feast. This striking parallel emphasizes how the lamb sacrificed by the Jews to...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

In their wonderfully lapidary styles, the synoptic Gospels describe what happens during the meal, albeit with varying orders of events. Matthew reports that while they are eating Christ says, “Amen I say to you that one of you is about to betray me.” The apostles, deeply troubled by the announcement, ask, “Is it I, Lord?” To which Christ responds, “He that dips his hand with me in the dish, he shall...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Following swiftly on the heels of this revelation comes the institution of the Eucharist. “Take and eat,” Christ tells them as he breaks the bread. “This is my body.” Taking the chalice, he gives thanks and says: “Drink all of this. For this is my blood of the new testament, which shall be shed for many unto remission of sins.” Matthew includes t...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Mark follows Matthew very closely, likewise placing the announcement of the betrayal immediately before the institution of the Eucharist. Luke, on the other hand, reverses the order of the two events. In his version, Christ breaks the bread and shares the wine before making the announcement of the betrayal. The communion appears to be under way, in fact, when Christ startles them with his dramatic declaration. “This is the chalice, the new testament in my blood, which shall be shed for you,” he tells them before immediately adding, “But yet behold: the hand of him that betrays me is with me on

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

John’s account of the events is somewhat different from the preceding Gospels. His was the last of the Gospels to be written down. The fourth-century historian Eusebius claimed that Mark and Luke had already composed their Gospels when John, who had been proclaiming his Gospel orally, decided to supplement their accounts with more details about Christ’s early ministry.3 His account of the Last Supper is likewise more detailed, though in his version the supper itself—which is clearly not the Passover meal—is finished very quickly. When the meal is over, Christ rises from the table, girds

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

These words echo those of the other Gospels, but John adds some of the most brilliantly dramatic passages in the entire Bible. As in the other Gospels, there is initially some confusion, consternation, and self-scrutiny as the men turn to one another, “doubting of whom he spoke.” John then provides further information about the responses. Leaning on Christ’s bosom is “one of his disciples, whom Jesus loved.” Modesty forbids John from identifying this beloved disciple, who is mentioned several mor...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The bewildered apostles demand clarification. Typically, it is Peter—blunt spoken and bighearted—who asks John, still leaning on Christ’s breast: “Who is it of whom he speaks?” John asks on behalf of the others: “Lord, who is it?” Christ offers the same reply as in the first two Gospels: “He it is to whom I shall reach bread dipped”—whereupon he dips the bread into the dish and hands the sop to Judas.

At this point John introduces an element entirely absent from the first two Gospels and only alluded to in passing by Luke. Before describing the Last Supper, Luke mentions how, as the high priest and the scribes debated how they might put Jesus to death, “Satan entered into Judas,” who then approached them with his promise to deliver Christ into their hands. John’s account is more elaborate. Unlike the others, he does not mention that Judas has already been involved in treacherous dealings with the high priest. If he has not made his traitorous bargain, then Judas must be as baffled as the

...more

A notable difference between John’s version of the Last Supper and that given in the synoptic Gospels is that John makes no mention of the institution of the Eucharist. Elsewhere, however, his Gospel abounds in reflections on the Eucharist. He explicitly mentions, in his account of the Passover feast one year earlier, the prospect of salvation through the body and blood of Christ. Following the miracle of the feeding of the five thousand, Christ tells the grateful multitude that he is “the bread of life” and that anyone who “eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him” (6:48,

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

In John’s account, Christ does not distribute the “bread of life” at the Last Supper. Instead, he offers only the single piece of dipped bread, which Judas then eats. Judas’s act of consuming the bread received from Christ’s hand turns the scene into an unholy counterpart to the Communion because, as John says, “after the morsel, Satan entered into him.” Christ then addresses Judas directly: “That which you do, do quickly.” Confusion reigns once again. This injunction puzzles the other apostles as much as his earlier statement about the betrayal, with some of them mistaken...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Judas, however, now knows exactly what Christ means, and what he must do, and he quickly disappears into the night. He will reappear several hours and five chapters later, with a band of soldiers and servants from the high priest and the Pharisees armed with “lantern...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Scenes of the Last Supper became ever more plentiful and conspicuous in fourteenth-century Italy, especially in the newly rediscovered medium of fresco. It was usually included as part of a Passion Cycle or scenes illustrating the life of Christ, but by the middle of the fourteenth century the episode was sometimes removed from this context and given a new prominence in a particular location: the refectories of convents and monasteries. Thus the nuns or friars would have sat at a table directly beneath a fresco of the apostles at their own table in Jerusalem. Last Suppers henceforth became

...more

A Last Supper was never an easy proposition, even on spacious refectory walls. The artist had somehow to fit around a table thirteen separate figures through whom he would illustrate either the moment when Christ instituted the Eucharist or announced, to general incomprehension, that one of the number would betray him. Painters like Castagno and Ghirlandaio had created compelling scenes through a subtle choreography of hands and expressions, ones that duplicated the hushed and reflective mood prevailing in the refectories.

Leonardo, however, probably saw in these delicate gestures and gently furrowed brows few tokens of the exuberant life that he himself hoped to capture in his own art. He also would have glimpsed little of the drama that he would have read about in the Bible’s version of these events. The story is, after all, extraordinarily emotive. Thirteen men sit down to dinner to observe a solemn feast: a charismatic leader and his band of brothers, carefully selected and endowed with special powers. They are gathered in the middle of an occupied city whose authorities are plotting against them, waiting

...more

he smoothly translated his observations into the context of a Last Supper. He outlined the distinctive reactions of these participants in terms of both their physical actions (lifting or upsetting a glass, holding a knife, recoiling backward, or leaning forward) and their facial expressions (furrowed brows, shaded eyes, and the bocca della maraviglia, or mouth of astonishment). He froze the moment in time so the spectator would see the dinner guests in midgesture, with the loaf of bread “half cut through” and the drinking glass still at the lips. The effect, as he planned it here, would

...more

Frescoists worked in a very precise manner. At the start of each working day, the mason troweled the intonaco on to a small patch of wall to which the artist added his pigments before it dried. Pozzo succinctly described the process. “It is called fresco painting,” he wrote, “because the painting must be performed on it while the plaster is still damp; and for this reason, the plaster must not be spread over a larger portion of the surface than can be painted in one day.”8 A fresco was therefore created section by section, day by day, with the painter working swiftly on small fields of wet

...more

Frescoists generally did not paint freehand on the wet plaster. One of the keys to fresco was the use of cartoons (from cartone, a heavy paper or pasteboard) to transfer the design to the wall. The cartoon, a full-scale template for the fresco, was created by scaling up the smaller designs, usually via a grid of proportional squares, and transferring them to a master cartoon made (depending on the size of the fresco) from a few to dozens or more pasted-together sheets of paper. This large cartoon, which for Leonardo’s Last Supper would have been almost thirty feet wide, was cut up into smaller

...more

Fresco therefore entailed a huge amount of time-consuming preparatory work before the first brushstroke of paint could be laid: designing and building the scaffold, mixing and troweling the plaster, and transferring designs from the cartoons, which were themselves the product of countless preliminary drawings and as many as several hundred sheets of paper (one famous surviving cartoon, Raphael’s for The School of Athens, a twenty-five-fo...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Despite Leonardo’s love of challenges, his lack of experience in this difficult medium would have given him pause. Furthermore, this technique of painting—of expeditiously adding pigments and then moving on to an adjacent section—was ill-suited to his manner of working. He was not someone who worked with “quickness and celerity.” The diary kept by Jacopo da Pontormo as he worked in the church of San Lorenzo in Florence gives a good sense of how the frescoist progressed. “On Thursday I painted those two arms,” he recorded. “On Friday I painted the head with the rock below it. On Saturday I did

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Oil paint had a number of distinct advantages over egg tempera. Most obviously, pigments blended with oil looked richer and glossier than those mixed with tempera. Oils allowed an artist a greater range of color values and tonal gradations because they could be blended either on the palette or (as Leonardo’s smudging fingerprints attest) on the pictorial surface itself. An artist could also vary the ratio of oil to pigment, resulting in a wide range of consistencies, anything from thin, translucent layers of color to dense impastos. He could heat his oil before the pigment was added to create

...more

Painting with oil had allowed Leonardo to capture the startling visual effects that were winning him his reputation as a painter: the moody half lights and misty atmosphere of The Virgin of the Rocks, the soft-focus facial expressions in his portraits of Ginevra de’ Benci and Cecilia Gallerani. His aptitude and experience in oil rather than fresco led him to consider painting his Last Supper in a technique different from the usual one: that is, by working with oils on a dry wall.

Leonardo’s punctilious approach to facial features was described in a work published in 1554 by a writer named Giovanni Battista Giraldi, whose story has some credibility because his father knew Leonardo and watched him paint in Santa Maria delle Grazie. Giraldi claimed that whenever Leonardo wanted to paint a figure, he first considered “its quality and its nature”: such things as whether the figure was to be happy or sad, young or old, and good or evil. Having determined these details, he would take himself off to a place “where he knew persons of that kind congregated and observed

...more

Christ is significantly larger than many of the other apostles: he is as tall as Bartholomew (the last figure on the left) even though Bartholomew is standing. So subtle in Leonardo’s hands that we barely notice it, this technique is a throwback to earlier centuries, when painters arranged their figures in what art historians call “hieratic perspective”—the practice by which figures are enlarged according to their theological importance (which explains why so many medieval paintings show enormous Madonnas surrounded by pint-sized saints and angels).

Besides occupying the center of Leonardo’s painting, Christ is spatially isolated from the apostles, all of whom are bunched together as they physically touch their neighbors or lean across one another in partial eclipses. Leonardo further highlighted Christ by placing him against a window that opens onto a landscape of clear sky and bluish contours—by giving him, in effect, a halo of sky. The effect is dazzling, even despite the paint loss, as the warm tones of Christ’s face, hair, and reddish undergarment advance while the cool blues of the landscape recede: a prime example of Leonardo’s

...more

How did people during the Italian Renaissance, when they looked at a painting of a biblical scene, know who they were looking at? How did they identify the often huge casts of saints and disciples with which frescoes and altarpieces teemed?

Until about 1300, painters often identified the figures in their painting by helpfully inscribing their names underneath—giving them, in effect, name tags. By the time of Giotto, these inscriptions largely disappeared and a tradition was established whereby painters used distinctive attributes to illustrate and individuate saints and biblical characters. Peter is easily recognizable because he is often shown holding a pair of keys (“I will give to you the keys of the kingdom of heaven,” Jesus tells him in the Gospel of St. Matthew). Sometimes, in reference to his former occupation, he might be

...more

Painters of Last Suppers did not bother with these symbols, which would have detracted from the pictorial effect. Even so, a number of the apostles were usually obvious to viewers because of their appearances or actions, especially the gray and grizzled Peter, the youthful John, and, of course, the villainous Judas. But artists were not always concerned to individuate the entire cast of twelve apostles. Lorenzo Ghiberti, in his bronze relief on the door of the Baptistery of San Giovanni, even depicted...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Art historians are confident, however, about the identities of the twelve apostles in Leonardo’s Last Supper. Their names were established when, in about 1807, an official from the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera in Milan, Giuseppe Bossi, discovered in the parish church of Ponte Capriasca, near Lake Lugano, a sixteenth-century fresco copy of Leonardo’s mural. Even though such inscriptions had virtually disappeared from Italian art, twelve names were carefully painted on a frieze underneath. These identifications, because they were pr...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Leonardo faced the same compositional problem as any painter of a Last Supper: how to range thirteen men around a dinner table such that they could interact with each other. A notable feature of his design for The Last Supper is how he arranged the twelve apostles in four groups of three, with two of these triads on either side of Christ. The most dramatic and intriguing of these groupings is the one immediately to the right of Christ, featuring—as the copy at Ponte Capriasca tells us—Judas, Peter, and John. Leonardo positioned John leaning away from Christ and t...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Anyone familiar with the Gospel of St. John would know exactly the moment depicted. “Amen, amen, I say to you, one of you shall betray me,” Jesus announces. “The disciples therefore looked one upon another,” John reports, “doubting of whom he spoke. Now there was leaning on Jesus’s bosom one of his disciples, whom Jesus loved. Peter ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Jesus is speaking of Judas, of course—but who is it of whom John speaks? The disciple leaning on the bosom of Jesus is not only in a privileged position at the dinner table, in physical contact with Jesus, but he is evidently privy to special knowledge about the betrayal, or at least so Peter believes.

The disciple leaning on Jesus—the one “whom Jesus loved”—is traditionally identified, as we have seen, as John himself. The Greek translators of the Bible had several different words for love at their disposal. Earlier in the Gospel of St. John (11:3) we are told that Jesus loves Lazarus, the brother of Mary and Martha whom he raises from the dead. His love for Lazarus is expressed by the Greek word philia, which refers to strong friendship or brotherly love. The Greek translation of the New Testament uses the word agape, on the other hand, to describe his feelings for John, connoting a much

...more

All Last Suppers portrayed John as a youthful and slightly feminine figure among his mostly bewhiskered and older companions. Virtually all of them, too, following the Gospel of St. John, showed him asleep on the bosom of Christ. From the twelfth century onward this motif was ubiquitous in Last Suppers, with Giotto in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, for example, showing Jesus cradling a sleeping John. All of the great refectory Last Suppers in Flor...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Leonardo’s approach to John was unique. Although one of his earliest sketches for the composition shows John asleep beside Christ, he abandoned the pose, undoubtedly because it detracted from the figure of Christ, whom he wished to isolate and emphasize in the middle of the scene. He therefore deviated from well-established pictorial tradition, illustrating a moment in the narrative that comes a second or two later than all others: having roused himself from Christ’s breast, John leans gracefully toward Peter, his head tipped to the right, the better to hear his urgent question: “Who is it of

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

By the 1490s, then, Mary Magdalene had a rich history and a wide range of meanings: prostitute, close companion of Christ, “apostle of the apostles,” patron saint of the Dominicans, miracle worker, virgin saint, and, most of all, reformed sinner—an example of how fallen humanity could redeem itself, and how even the most lowly and despised could be called by Christ to an apostolic mission. She was prolifically represented in frescoes and altar-pieces. There could be nothing controversial or theologically untoward about her appearance in a painting showing Christ and his apostles.

A figure in a Leonardo painting with feminine features does not therefore automatically, easily, or unambiguously qualify as a woman. In fact, the figure in The Last Supper is not a woman: only the most partisan reading can place Mary Magdalene in the scene. Viewers in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries would have read the painting quite differently.

As we have seen, a well-established tradition gave John, the beloved disciple, a feminized appearance and sat him beside Christ—or often placed him asleep on Christ’s breast—at the Last Supper. He was traditionally understood to be the youngest of the apostles, and painters made much of his youthfulness. The earliest known image of him, in the St. Tecla catacomb in Rome, dating from the late fourth century, shows him as slim and beardless, little more than a boy. Painters of the Last Supper invariably depicted him as a handsome, beardless, and often effeminate youth with long hair. Leonardo

...more

None of the three synoptic Gospels mentions the special relationship between Jesus and John, and the Bible itself provides only a few details of John’s life and character. John is not even mentioned in his own Gospel beyond several cryptic references to the disciple whom Jesus loved most. From the synoptics it can be determined that he was the brother of James the Greater and the son of a fisherman named Zebed...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

wine was regularly (and copiously) served with meals, both in the refectory and in the family home, in part because its alcoholic content meant that, unlike water, it was free from bacteria and other pathogens.

With his right hand Jesus reaches toward the same dish to which Judas, two seats away, is likewise reaching. As they approach the dish, their two hands, skillfully foreshortened and almost mirror images of one another, suggest the line from Matthew: “He that dips his hand with me in the dish, he shall betray me.” Yet the dish, and Judas’s guilty hand, are not the only objects that Jesus’s hand approaches: he is reaching, simultaneously, for the wineglass in front of him. Indeed, two joints of his pinkie and the ball of his third fingers are seen, in yet another bedazzling show of painterly

...more

The left hand of Jesus is likewise in motion, indicating—with much subtlety and restraint in the midst of so much frantic gesticulation—the bread that sits within easy reach. More than that: Jesus is looking directly at the bread, which, despite the commotion that surrounds him, is the sole object of his gaze. Leonardo was extraordinarily astute in his understanding of visual perception, and through single-point perspective he carefully controlled how the viewer experiences his painting. The perspective draws our attention to the face of Christ at the center of the composition, and Christ’s

...more