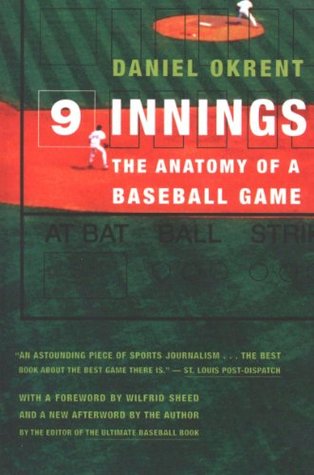

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

The team Bob Rodgers took north in April of 1982 had been expected to contend for a pennant, yet the only contention in the season's first two months had been in the clubhouse, on the plane, in the dugout.

The hoariest of pitching doctrines holds that one pitch "strength to strength": faced with a batter who loves high sliders, say, the pitcher whose best pitch is a high slider would still throw it. It seems a foolhardy idea, predicated on blind macho, but in most cases it is as strategically sound as it is noble. At the tactic's heart is an expression of self-confidence, of true belief: you may be good, but I'm better; beat me if you dare. The pitcher who thinks, "I can't beat you," usually takes his self-doubt with him to the showers.

But what Weaver could do that no other manager could do so well was recognize talent, and know its limitations.

In the late 1970s, New York Times writer Tony Kornheiser found himself in the Yankee dugout with several other reporters and the New York manager, Bob Lemon, whose years of bibulousness had left their evidence on his face. "Tell me, Bob," Kornheiser asked in a lull in the conversation, "are you aware of your nose?"

(One of Uecker's favorite stories concerned signing his original contract with the old Milwaukee Braves. "They said 'three thousand dollars,' "Uecker related, "but my dad didn't have that kind of money.")

Seeking a white knight who could cleanse the stains of scandal, the baseball owners turned to federal district judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis; in Will Rogers' words, "Somebody said, 'Get that old boy who sits behind first base all the time. He's out there every day anyhow.' So they offered him a season's pass and he jumped at it."

It was a variant of the situation Bill Veeck, then owner of the St. Louis Browns, had found himself in twenty-nine years earlier, when 20-game winner Ned Garver had asked for a raise. Veeck told him, "We finished last with you. It's a cinch we can finish last without you."

Dalton put it, "Not every phenom phenominates."

In a lifetime of scouting, Youse had seen only one amateur ball player he considered an 8—a young Pennsylvanian named Reggie Jackson.

(Felske's successor as Milwaukee's Double A manager, Lee Sigman, hadn't quite the same decisiveness: coming out to the mound to remove pitcher Dwight Bernard from a Triple A game in 1981, Sigman asked for the ball and Bernard said, "Fuck you, Siggy. Get lost." Sigman retreated to the dugout. At season's end, he was made a scout and minor league instructor.)

There is no evidence at all that happy teams win more games than grumpy teams; the egg of success usually precedes the chicken of contentment, and not the other way around.

But pennants are not won by one hit, or even one game, despite what the standings say. The roots of the Milwaukee success in 1982 (they went on to win the American League pennant playoffs against the California Angels, then lost the World Series in seven games to the St. Louis Cardinals, who had a young outfielder named David Green in the lineup) stretched back months and years, in countless directions: to Jim Gantner's fortuitous twelfth-round selection in the 1974 draft, to Bud Selig's support of Harvey Kuenn during his physical tribulations in the late 1970s, to Harry Dalton's

...more

The powerful team Harry Dalton had assembled came apart in the only fashion that these things happen: suddenly.

What's worse, they compete in a three-tiered, basketball-style playoff system so antithetical to the entire theology of the long season that the very term "pennant race" may soon be extinct.