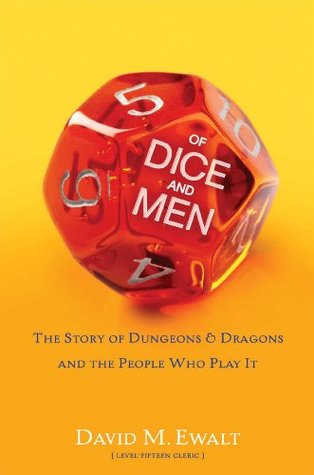

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

the game and return it to its roots as a battlefield simulation. In 1664, Christopher Weikhmann of Ulm, Germany, created Kőenigsspiel, the King’s Game, boasting that it would “furnish anyone who studied it properly a compendium of the most useful military and political principles.” Weikhmann increased the number of pieces on each side to thirty, replacing antiquated knights and bishops with then-modern military units like halberdiers, marshals, and couriers. He also created variant rules for up to eight players, expanding the board to more than five hundred squares.

In 1780, Johann Christian Ludwig Hellwig, “master of pages” in the court of the Duke of Brunswick, went even further. His “war chess” board consisted of more than 1,600 squares, each color-coded to indicate terrain: white for level ground, green for marshes, blue for water, red for mountains. There were hundreds of pieces, each one a colored chit representing an entire military unit, including batteries of mortars, pontoon boats, and regiments of hussar cavalry. The rules became so complicated that Hellwig required the participation of a neutral third party to direct the game and settle

...more

In the early days of the Napoleonic wars, Georg Leopold von Reiswitz, a Prussian civil servant, wanted to play Hellwig’s War Chess, but couldn’t affo...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

1812 as Instructions for the Representation of Tactical Maneuvers Under t...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

In the 1860s, under Otto von Bismarck, the game became a standard training exercise for Prussian officers. When two decades of military success followed, Kriegsspiel basked in reflected glory: After the Franco-Prussian War, British generals cited it as a factor in von Bismarck’s decisive victory. Armies around the world copied the game and began using it to train their own officers.

1913, the British novelist H. G. Wells took his own stab at the genre, publishing Little Wars: A Game for Boys from Twelve Years of Age to One Hundred and Fifty and for That More Intelligent Sort of Girl Who Likes Boys’ Games and Books. The text amounted to Kriegsspiel for Kiddies: a short, simple, accessible set of rules. Wells did away with complicated boards, encouraging play on a kitchen table or bedroom floor. And he ditched the counters and markers that represented military units: Little Wars required only a child’s own collection of tin soldiers.

The general public proved more interested in simple, self-contained board games like Monopoly, which debuted in the 1930s, and Scrabble, first published in 1948. Kriegsspiel and its brethren continued to have their fans, but they were few in number, almost exclusively older men, and usually veterans who wanted to relive a bit of the thrill of the world wars.

In 1952

Charles R...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Tactics,

In 1954, “almost as a lark,” Roberts decided to manufacture and sell the game to the public. It sold only two thousand copies in the next five years, but Roberts saw an untapped market for adult board games and pressed on. In 1958, he designed and published Gettysburg, which simulated the American Civil War battle; it was a hit, and by 1962 Roberts’s Avalon Hill game company was the fourth-largest producer of board games in the United States.

1964

Before long, the meetings were crowded and increasingly contentious, as the old problem of bickering over rules reared its head. A solution was found in the form of an eighty-year-old army training manual, Strategos: A Series of American Games of War, published in 1880 by Charles A. L. Totten, a lieutenant in the Fourth United States Artillery. Dave Wesely, an undergraduate physics student at Saint Paul’s Hamline University, unearthed the book in the University of Minnesota library and rediscovered the centuries-old idea of an all-powerful referee. It quickly became standard practice.

1967,

What he came up with was the first modern role-playing game. The scenario was set during the Napoleonic Wars, in the fictional town of Braunstein, Germany, surrounded by opposing armies. But Wesely didn’t put the armies on the board. Instead, he assigned each player an individual character to control within the scenario. Some players controlled military officers visiting town. Others took nonmilitary roles, like the town’s mayor, school chancellor, or banker. Wesely then gave each player their own unique objective, forcing them to consider motivations for their actions and to think beyond

...more

David Wesely’s innovations—using a referee, assigning players individual characters with unique objectives, and giving them the freedom to do whatever they want—lit a fire in the Twin Cities gaming community. His Braunstein role-playing adventures appealed to players who were tired of long, complicated war reenactments and got them thinking about where the games could go next. It wasn’t long before others began to follow his example.

David Arneson1 was

The players were nonplussed—save for the delighted commander of the British druid. But Arneson wasn’t put off from sneaking elements of fantasy into his war games. In December 1970, after a two-day binge of watching monster movies and reading Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian books, Arneson invited his friends over under the pretense of playing a traditional Napoleonic war game. Instead, he introduced them to the city of Blackmoor.

The game was so popular, people wanted to play even when they couldn’t make it to Arneson’s house and would call him on the phone to lead them on solo adventures through the dungeons.

first, combat in the world of Blackmoor was resolved using a clunky system of rock-paper-scissors showdowns. But Arneson quickly turned to the rules of a medieval-miniatures war game called Chainmail, paying particular interest to two sections of its sixty-two-page booklet: “Man-to-Man,” which explained how to manage individual heroes amongst your army, and “Fantasy Supplement,” which included rules for casting magical spells and fighting hideous monsters.

To that end, Gygax decided to organize a war-gaming convention. He rented out the Lake Geneva Horticultural Hall for fifty dollars, and on August 24, 1968, he welcomed friends and IFW members to “Gen Con”—a double pun referring to both the rules of war and the event’s location. Admission cost a dollar, and the show made just enough money to cover the rental.

In August of 1969, Gygax held the event again. This time, IFW member Dave Arneson drove from Saint Paul to check out the action, and the two gamers spent a lot of time together. “Since we’re only talking a couple hundred people at that point, we pretty much ran into each other all the time,” Arneson said. “We were both interested in sailing-ship games.”

1971’s Chainmail, written by Gygax and his friend Jeff Perren, which provided a starting rule set for Dave Arneson’s Blackmoor campaign;

and 1972’s Don’t Give Up the Ship!, authored by Gygax, Arneson, and war-gaming friend Mike Carr, the result of their ongoing discussion about naval warfare.

Here’s my attempt: Two young men meet in the late 1960s and bond over a shared love of a nerdy pastime. They both belong to the same hobbyist’s club and start making things to share with the other members. Before long, they’re working together on something new and exciting. One of them is the engineer; he invents new ways of doing things. The other is the visionary; he realizes the potential. The product they create could not have existed without both of them. When it’s released, it launches a brand-new industry and changes the world.

By the end of 1972, he’d finished a fifty-page first draft. He called it the Fantasy Game. The first people to play it were Gygax’s eleven-year-old son, Ernie, and nine-year-old daughter, Elise. Gygax had created a counterpart to Arneson’s Blackmoor, which he called Castle Greyhawk, and designed a single level of its dungeons; one night after dinner, he invited the kids to roll up characters and start exploring. Ernie created a wizard and named him Tenser—an anagram for his full name, Ernest.3 Elise played a cleric called Ahlissa. They wrote down the details of their characters on index cards

...more

Now they only had to print it. In the summer of 1973, Gygax called Avalon Hill and asked if they were interested in publishing his game. “They laughed at the idea, turned it down,” Gygax wrote.6 Most of the gaming establishment wanted nothing to do with Arneson and Gygax’s weird little idea. “One fellow had gone so far as to say that not only was fantasy gaming ‘up a creek,’ ” wrote Gygax, “but if I had any intelligence whatsoever, I would direct my interest to something fascinating and unique; the Balkan Wars, for example.”

In January 1974, Tactical Studies Rules made its creation public. It cost $10 and came in a hand-assembled cardboard box covered in wood-grain paper. A flyer pasted to the top lid featured a drawing of a Viking warrior on a rearing horse—art copied from a Doc Strange comic book. Gygax and Arneson’s names were also on the cover, and above that was the title: DUNGEONS & DRAGONS Rules for Fantastic Medieval Wargames Campaigns Playable with Paper and Pencil and Miniature Figures