More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

September 14 - September 24, 2025

“Say it, Ethel, what I told you to say, that you’re mistaken—or I’m slapping your face right here, in front of Dr. Weeks, in front of the Medfords, in front of Ron’s friends, in a way you won’t forget. Ethel—”

My mother hated me, and my father cut me off. I was left at the mercy of the Medfords, who I think hated me too, just to make it unanimous.

Now my mother had said to me once, “You’ll be told: Don’t talk about the weather. Joan, always talk about it. It’s the one thing everyone has in common with everyone else, and often the only thing to talk about. Talk isn’t always so easy—talk about what you can talk about.”

She saw me about to say something and interrupted before I could. “… And if you think it funny that I have a regular boyfriend when I told you I sometimes go with other men, too, picked up in the bar, well—so do I. I don’t pretend to understand it. But I keep doing it, and I won’t tell you it’s just for the extra money.” “What else is there?” “Their asking, I guess,” she said. “They’re so eager sometimes. It takes the curse off gray hair. You know what I mean, Joanie? At a certain age, we need assurances.” I set down the coffee things. “At any age, Liz.”

I may have said more, especially about Ethel, all the time wishing I hadn’t, as I wished he hadn’t said what he did about his stepchildren and what rats they were—one of the first things I had learned at home was: Don’t wash family linen in public, or with anyone except family. And I wish I could say I got to talking that way because of the way I felt, the way Ethel was bugging me, but it wouldn’t be true. I did it because I knew without being told, from the way he was lining it out, it was the kind of talk that he liked. So, from the beginning, I knew there was something about him I didn’t

...more

“Please don’t say anymore. You make me very uncomfortable.” “I regret that very much, Mrs. Medford. My intent was the opposite.” His eyes held mine, and I could see kindness in them. Or what I thought was kindness—you can never be certain. “As I say, they don’t teach it at the academy, but you learn it on the job: not every man’s death is a crime.”

“With angina, marriage is out. To you or anyone. As my doctor has warned me repeatedly, I can’t … be with a woman. He’s quite certain, my heart wouldn’t stand up to the strain. Or in other words, marriage, with you, for me, would be a sentence of death. That’s the fantastic torment I live in: I’ve never met a woman I’ve wanted more, I think about you to the point of distraction, of insanity we could say, but if I do about it what any normal man wants to do, I die.”

“Casanova, somewhere in his memoirs, says a woman knows only one way of expressing gratitude. If that way had occurred to you, the consequences could have been catastrophic.”

“It’s a fiendish sentence to live under. I realize we haven’t known each other for very long, but there is no mistaking how you make me feel, and I know how rare it is, and if it weren’t for this thing I’d give my eyes to marry you, to be with you morning, noon, and night—all the time. But it can’t be.” “You make me want to cry.” “While you’re about it, cry for me.”

“Now he’s thinking.” “I do apologize, Joan, if you want me to, for being drunk and giving in to temptation, but I won’t apologize for the temptation itself, since I’m just as tempted now, maybe more so.” It was not the apology I’d been waiting for, but it set my blood racing as that apology never would have.

Then I went in, walked back to the bedroom and had a look around, as well as in my bag, to make sure I had everything. It was a big one I’d had from Pittsburgh, and the only one I was taking, as that was one thing I’d learned from my father, one of the few memories of him I respected: “Take one bag and one bag only—it’ll hold what you need, if you use the facilities available where you go—the laundry, the cleaner, the bootblack, the barber, the beauty parlor—let them freshen you up. Don’t try to take the whole clothes-closet with you.”

fortuitous,

You learn, often the hard way, that satisfying a craving is no guarantee you end up satisfied in the long run.

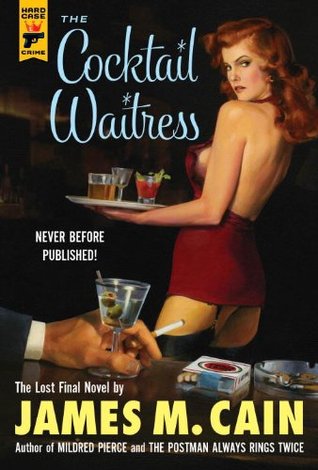

The brilliant, exquisitely talented Raymond Chandler, Cain’s contemporary and peer (and incidentally the co-author of the Oscar-nominated screenplay for Double Indemnity), was one of those who loathed Cain. He wrote, with characteristic eloquence and pungency, “He is every kind of writer I detest … a Proust in greasy overalls, a dirty little boy with a piece of chalk and a board fence and nobody looking.” But Chandler had it wrong. He thought this description of Cain was a condemnation, when in fact it was a badge of honor. And everyone was looking.