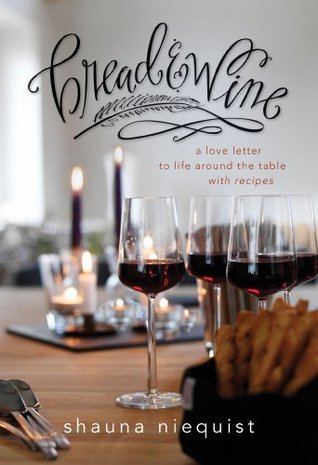

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

October 6 - October 24, 2024

I learned the deeper practices of hospitality—not just parties and planned gatherings, but a way of living with an open door and an open heart, a way of using food and time and attentiveness as a way of loving people.

Both the church and modern life, together and separately, have wandered away from the table. The church has preferred to live in the mind and the heart and the soul, and almost not at all in fingers and mouths and senses.

part of becoming yourself, in a deeply spiritual way, is finding the words to tell the truth about what it is you really love. In the words of my favorite poet, Mary Oliver, it’s about “letting the soft animal of your body love what it loves.”

But I do want you to love what you eat, and to share food with people you love, and to gather people together, for frozen pizza or filet mignon, because I think the gathering is of great significance.

It’s about a spirit or quality of living that rises up when we offer one another life itself, in the form of dinner or soup or breakfast, or bread and wine.

To feed one’s body, to admit one’s hunger, to look one’s appetite straight in the eye without fear or shame—this is controversial work in our culture.

The extra pounds didn’t matter, as I look back, but the shame that came with those extra pounds was like an infectious disease. That’s what I remember. And so these days, my mind and my heart are focused less on the pounds and more on what it means to live without shame, to exchange that heavy and corrosive self-loathing for courage and freedom and gratitude.

I’m talking about feeding someone with honesty and intimacy and love, about making your home a place where people are fiercely protected, even if just for a few hours, from the crush and cruelty of the day.

She said, “When you feel like shattering something, I’ll be right there with you. We’ll put on our safety goggles. I’ll help you break something, and then I’ll help you clean it up.” She said, “You’ve been celebrating with me, and I’ll be here to grieve with you. We can do this together.”

Enough: I don’t want to live like that anymore. And enough: I have enough. I have more than I need, more than I could ask for.

I want to cultivate a deep sense of gratitude, of groundedness, of enough, even while I’m longing for something more. The longing and the gratitude, both. I’m practicing believing that God knows more than I know, that he sees what I can’t, that he’s weaving a future I can’t even imagine from where I sit this morning.

What I learned more than anything else that week is that we learn by doing. We learn with our hands and our noses. We learn by tasting the stock, feeling the hum of the knife back and forth, listening for the sounds of hot oil.

You learn it, really learn it, with your hands. With your fingers and your knife, your nose and your ears, your tongue and your muscle memory, learning as you go.

And I knew in some wordless way that I needed that sandwich more than a person should need a sandwich. I wanted, in the most obvious way, rest and care and nourishment, a sense of comfort and peace.

I didn’t want to be run by my appetites. I felt like I was stuffing myself with food, wine, people, books, experiences, things to do. I was unbelievably productive, like a crazy Energizer Bunny, but even when I was tired, I was still consuming—wine, shows, magazines, books. I was all feasting and no fasting—all noise, connection, go; without rest, space, silence.

What I’m finding is that when I’m hungry, lots of times what I really want more than food is an external voice to say, “You’ve done enough. It’s OK to be tired. You can take a break. I’ll take care of you. I see how hard you’re trying.” There is, though, no voice that can say that except the voice of God.

What heals me on those days when it all feels chaotic and swirling is the simplicity of home, morning prayer, tea, and breakfast quinoa.

But I have also long held the belief that one’s tears are a guide, that when something makes you cry, it means something. If we pay attention to our tears, they’ll show us something about ourselves.

But when I traveled with my dad, he taught me that wherever we are, we eat what they eat, and we eat what they give us, all the time. We taste the place when we eat what our hosts eat. As we traveled, food became a language for understanding, even more so than museums or history lessons.

I want my kids to learn firsthand and up close that different isn’t bad, but instead that different is exciting and wonderful and worth taking the time to understand. I want them to see themselves as bit players in a huge, sweeping, beautiful play, not as the main characters in the drama of our living room.

What people are craving isn’t perfection. People aren’t longing to be impressed; they’re longing to feel like they’re home. If you create a space full of love and character and creativity and soul, they’ll take off their shoes and curl up with gratitude and rest, no matter how small, no matter how undone, no matter how odd.

You’ll miss the richest moments in life—the sacred moments when we feel God’s grace and presence through the actual faces and hands of the people we love—if you’re too scared or too ashamed to open the door.

It would have been lovely to learn those things on my own terms, when I wanted to, the way I wanted to. But we never grow until the pain level gets high enough.

forced me to embrace the risky but deeply beautiful belief that love isn’t something you prove or earn, but something you receive or allow, like a balm, like a benediction, even when you’re at your very worst.

She teaches me, through her words and her actions, that if you take the next right step, if you live a life of radical and honest prayer, if you allow yourself to be led by God’s Spirit, no matter how far from home and familiarity it takes you, you won’t have to worry about what you want to be when you grow up. You’ll be too busy living a life of passion and daring.

My mom makes sixty look good, and she reminds me every day that honest prayers transform us, that the world is big and beautiful and waiting for us, and that the best is yet to come.

But I’m using the word fasting these days as an opposite term to feasting—yin and yang, up and down, permission and discipline, necessary slides back and forth along the continuum of how we feed ourselves.

I’m learning that feasting can only exist healthfully—physically, spiritually, and emotionally—in a life that also includes fasting.

Fasting gives me a chance to practice the discipline of not having what I want at every moment, of limiting my consumption, making space in my body and in my spirit for a new year, one that’s not driven by my mouth, by wanting, by consuming.

the very things you think you need most desperately are the things that can transform you the most profoundly when you do finally decide to release them.

My work these days is to find that fine balance—allowing my senses to taste every bite of life without being driven by appetites, indiscriminate and ravenous.

Or I can choose to rest my body and nourish my spirit, knowing that taking a grounded, present self to each holiday gathering is more important than the gifts I bring.

90 percent of the people in your life won’t know the difference between, say, fresh and frozen, or handmade and store-bought, and the 10 percent who do notice are just as stressed-out as you are, and your willingness to choose simplicity just might set them free to do the same.

Either I can be here, fully here, my imperfect, messy, tired but wholly present self, or I can miss it—this moment, this conversation, this time around the table, whatever it is—because I’m trying, and failing, to be perfect, keep the house perfect, make the meal perfect, ensure the gift is perfect.

We have, each one of us, been entrusted with one life, made up of days and hours and minutes. We’re spending them according to our values, whether or not we admit it.

I pray that we’ll understand the transforming power that lies in saying no, because it’s an act of faith, a tangible demonstration of the belief that you are so much more than what you do.

The heart of hospitality is creating space for these moments, protecting that fragile bubble of vulnerability and truth and love.

All that to say, they are very real, very normal children, not angels or devils, just children—difficult and sweet and exhausting and wonderful all in the same moment, all the time.

It’s my job, my honor, to walk him, quite literally, from baby to toddler to boy to man.

One thing Aaron and I remind each other about all the time is that kids aren’t vanity projects, and they’re not extensions of our own images.

He’s a person, not a paper doll. And we’re his parents, not his marketing team.

She said you carry them inside you, collecting them along the way, more and more and more selves inside you with each passing year, like those Russian dolls, stacking one inside the other, nesting within themselves, waiting to be discovered, one and then another.

I try to feed myself with care and attentiveness, without shame, without punishment. In some seasons, I choose discipline, not because I’m out of control, not as a punishment, but because it heals me, helps me, and builds and resets something good inside me.

I’m realizing this after what seems like a lifetime of saying to myself, “Well, you can’t be expected to do something hard on a day like this, can you?” I did expect more from myself, and I did do something hard, and I’m thankful.

But entertaining isn’t a sport or a competition. It’s an act of love, if you let it be. You can twist it and turn it into anything you want—a way to show off your house, a way to compete with your friends, a way to earn love and approval. Or you can decide that every time you open your door, it’s an act of love, not performance or competition or striving. You can decide that every time people gather around your table, your goal is nourishment, not neurotic proving. You can decide.

We fragment our minds for a reason, of course—because we like the idea of being sixty-seven other places instead of the one lame, lonely place we find ourselves on some days.

When we want something to be momentous, it rarely is. Life is disobedient in that way, insisting on surprising us with its magic, stubbornly unwilling to be glittery on command.

That’s what shame does, though. It whispers to us that everyone is as obsessed with our failings as we are.

Shame tells us that we’re wrong for having the audacity to be happy when we’re so clearly terrible. Shame wants us to be deeply apologetic for just daring to exist.