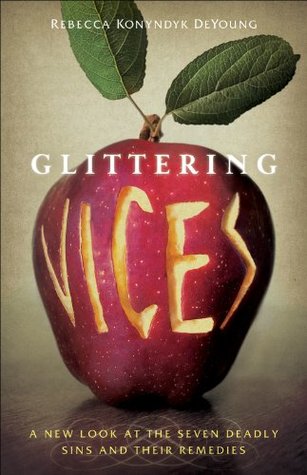

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

pusillanimity, which means “smallness

His central focus and framework is the people of good character we are meant to become. The pursuit of righteousness and moral excellence is the primary task—not obsession with the sins that so often entangle.

Virtues are “excellences” of character, habits or dispositions of character that help us live well as human beings.

Very simply, a virtue (or vice) is acquired through practice— repeated activity that increases our proficiency at the activity and gradually forms our character.

Virtue often develops, that is, from the outside in. This is why, when we want to re-form our character from vice to virtue, we often need to practice and persevere in regular spiritual disciplines and formational practices for a lengthy period of time.

The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle called this the difference between acting according to virtue—that is, according to an external standard which tells us what we ought to do whether we feel like it or not—and acting from the virtue—that is, from the internalized disposition which naturally yields its corresponding action.

The tradition eventually singled out seven virtues—three theological virtues (faith, hope, and love) and four cardinal virtues (practical wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance).

The desert fathers’ classification of seven vices began as a Christian system of self-examination in the fourth century and continued to provide an almost ubiquitous rubric for confession in penitential manuals up until the fifteenth century—an endurance that testifies to their power as a spiritual tool for confession and repentance.

As far as historians can tell, this list of vices was first put in writing by Evagrius of Pontus (346–399 AD), one of the desert fathers in the early centuries of the Christian church.

Evagrius set down a list of eight “thoughts” or “demons” that typically beset the desert hermit: “gluttony, then impurity [i.e., lust], avarice, sadness, anger, acedia [later called sloth], vainglory, and last of all, pride.”

Evagrius's List

A baseball player who expects to excel in the game without adequate exercise of his body is no more ridiculous than the Christian who hopes to be able to act in the manner of Christ when put to the test without the appropriate exercise in godly living.

William Gass freely comments: So what about lust?

The seven vices are not just any seven bad habits. Nor are they the worst possible or most frequent vices, although some critics mistakenly think this,

So he defines mortal sins as sins against charity.

but do not themselves sever our union with God.

We have seen that Gregory pared the list down to seven by designating pride, traditionally understood as the original sin, as the originator or root of all other vices.

For now, we should note that the list of seven vices does not directly correlate with the seven principal virtues—faith, hope, charity, practical wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance.

Avarice or stinginess, on the one extreme, names an excessive attachment to money,

A glance at the virtues with which he associates the seven vices yields the following conclusions:

The vices offer subtle and deceptive imitations of the fullness of the human good, what we often simply call “happiness.”

When our character is distorted by vice, we seek these goods—and they are genuinely good things—in a misguided or even idolatrous manner: in the wrong way, at the wrong times and wrong places, too intensely, or at the expense of other things of greater value.

Identifying and struggling against vice is not a purely human endeavor, and it is not an individualistic, psychological self-help program. It was and is the graced and disciplined formation of the body of believers seeking to become more and more like Jesus Christ.

Of all the deadly sins, only envy is no fun at all.—Joseph Epstein

The envious person resents another person’s good gifts because they are superior to his or her own. It’s not just that the other person is better; it is that by comparison their superiority makes you feel your own lack, your own inferiority, more acutely.

Envy is similar to covetousness in that both involve wanting something that belongs to another, something we ourselves lack.

But the envious and the covetous don’t want to “have one too.” They want the very thing the rival has—“I want that one, the one she has.

While the covetous person’s desires are focused on having an object, however, the envier is at least as concerned that her rival not have it.

Covetousness, like greed, tends to be more focused on possessions— things we have or own—than envy does.

In this way, envy—like jealousy—concerns love, between persons and for ourselves.

Although we commonly use jealousy and envy synonymously, jealousy is the condition of loving something and possessing it, and then feeling threatened because the loved thing or person might be taken away.

The jealous are those who “have” something they love which they might lose. The envious, by contrast, are the “have-nots”—they do not have the good their rival does, and they do not have self-love. Thus, they have nothing to lose and everything to gain from another’s loss.

The bottom line for the envious is how they stack up against others, because they measure their self-worth comparatively. The envious sorrow over another’s good because it excels their own,4 and because the comparison reveals not only their lack of that particular good but also their consequent lack of worth.

As Francis Bacon put it, “Envy is ever joined to the comparing of a man’s self; and where there is no comparison, no envy.”5

Envy involves a sense of inferiority, which breeds a lack of self-love.

This is not something Salieri can buy or attain with more hard work.

When the envious are forced to confront a self they judge lacking in worth, their unhappiness and grief can be unbearable. They feel compelled to do something—anything—to get themselves out from under it. Usually this means sabotaging the rival, but even this cannot rescue the envier from stewing in her or his own self-made resentments.

According to one confessional manual,6 envy can show itself in the following ways:

According to Aquinas, envy typically starts with “detraction,” more commonly known as backstabbing, for instance, a little murmuring in the shadows about the book’s weaknesses and the author’s somewhat shoddy research.

If these methods of trying to detract from their rival’s excellence are successful, and the rival’s reputation is damaged, the envious rejoice at the other’s downfall (Schadenfreude).

Hatred’s object is whatever blocks our own happiness.

Langland’s Piers Plowman:

To come out in the open and declare one’s envy is to admit and display one’s inferiority. This sense of inferiority is essential to envy.

Once there was an Englishwoman, a Frenchman, and a Russian:

As Buechner says, envy’s trademark is to desire that “everyone else [be] as unsuccessful as you are.”12 Just how to secure the satisfaction of that desire is the problem.

If we think about the people we envy, and why we envy them in particular, a pattern emerges. Enviers don’t usually envy those who are far removed from their lives and lifestyles, or who are vastly more talented or successful than they are. They tend to envy people to whom they might actually be compared unfavorably, that is, those who are just like them—only better.

Harold is driven to excellence and devoted to winning, because he is afraid to lose. This is the envier’s mentality.

Harold’s attitude is like the envier’s: he is defensive, afraid of being shown inferior, happy with himself only when he outranks all his competition in excellence. His identity and worth depend on his being better than another.

God. “When I run,” he tells her passionately, “I feel God’s pleasure.” When I run—not when I win

When we envy, our love for ourselves is conditional on excelling our rival. This is why Aquinas locates the vice of envy in the will—the same place he locates the virtue of love.