More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“Never make a mistake they can take a picture of.”

Barbara Ryckeley, an officer with Southwest Citizens, pointed out that not just Peyton Forest but all of white Atlanta was “endangered” by black expansion. “If the whites could just win once,” she explained, “they would have some hope for holding out.

“If those barricades hadn’t been put up,” an unnamed “Negro leader” was quoted as saying, “I don’t think Lynhurst would have been bothered.”

small groups of robed Klansmen stood guard at the barricades on Monday and Tuesday night. Patrolling the street, they held aloft signs: “Whites Have Rights, Too.”

“The City Too Busy to Hate,” the skeptics noted, had become “The City Too Busy Moving to Hate.”

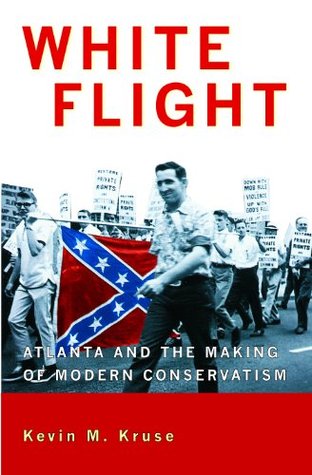

This book explores the causes and course of white flight, with Atlanta serving as its vantage point.

that it represented a much more important transformation in the political ideology of those involved. Because of their confrontation with the civil rights movement, white southern conservatives were forced to abandon their traditional, populist, and often starkly racist demagoguery and instead craft a new conservatism predicated on a language of rights, freedoms, and individualism. This modern conservatism proved to be both subtler and stronger than the politics that preceded it and helped southern conservatives dominate the Republican Party and, through it, national politics as well. White

...more

As compelling as this traditional interpretation of massive resistance has been, it suffers from a focus that stresses the words and deeds of top-level politicians over the lived realities of everyday whites.

This study, however, argues that white resistance to desegregation was never as immobile or monolithic as its practitioners and chroniclers would have us believe. Indeed, segregationists could be incredibly innovative in the strategies and tactics they used to confront the civil rights movement. In recent work on the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century South, several historians have argued that the system of racial segregation was never a fixed entity, but rather a fluid relationship in which blacks and whites constantly adjusted to meet changing circumstances.14

Ultimately, the mass migration of whites from cities to the suburbs proved to be the most successful segregationist response to the moral demands of the civil rights movement and the legal authority of the courts.

Although the suburbs were just as segregated as the city—and, truthfully, often more so—white residents succeeded in convincing the courts, the nation, and even themselves that this phenomenon represented de facto segregation,

By withdrawing to the suburbs and recreating its world there, the politics of massive resistance continued to thrive for decades after its supposed death.

But, like all people, they did not think of themselves in terms of what they opposed but rather in terms of what they supported.

The true goal of desegregation, these white southerners insisted, was not to end the system of racial oppression in the South, but to install a new system that oppressed them instead.

In the end, this work demonstrates that the struggle over segregation thoroughly reshaped southern conservatism. Traditional conservative elements, such as hostility to the federal government and faith in free enterprise, underwent fundamental transformations. At the same time, segregationist resistance inspired the creation of new conservative causes, such as tuition vouchers, the tax revolt, and the privitazation of public services.

And by solely examining the conservative political outlook in that overwhelmingly white and predominantly upper-middle-class environment, these observers have often failed to appreciate the importance of race and class in the formation of this new conservative ideology.

Instead, the tale balanced on the moderate coalition that controlled the city in the postwar era. During those decades, an unlikely collection of moderate white politicians, elite businessmen, and African American leaders dictated the pace of racial change.

In the end, court-ordered desegregation of public spaces brought about not actual racial integration, but instead a new division in which the public world was increasingly abandoned to blacks and a new private one was created for whites.

In reaction, working-class whites were furious. Throughout the late 1950s they held bitter protests to prevent the “loss” of their buses, golf courses, parks, and pools. In the end, however, the combined power of the courts, the city’s upper-class whites and the civil rights community overwhelmed their “defensive” efforts. Within a few years, all of the city’s public spaces were thoroughly desegregated. Ultimately, the failed fight over these spaces showed working-class whites that there was a growing chasm between their own commitment to segregation and the commitment of wealthier whites. In

...more

improvements which they assumed would solely benefit blacks. In a broader sense, however, their anger over the desegregation of public spaces dovetailed with their anger over the desegregation of their neighborhoods to prompt their flight from the city. Their withdrawal was physical, of course, as working-class whites abandoned the city for the still-segregated suburbs. But their retreat also took place in a larger sense, as working-class whites withdrew their support—financial, social, and political—from a society that they felt had abandoned them.

White riders, however, were even less anxious to “mix” with blacks. Census reports from 1960 demonstrate that, as some had predicted, whites had indeed fled the system and taken to private cars in large numbers. In several neighborhoods, working-class whites now used private cars to get to their jobs instead of public transportation, by a 2-to-1 margin. Meanwhile, blacks in neighboring tracts—sections that were likely to share

bus routes with these white areas—trended in precisely the opposite direction, choosing public transportation over private cars by a 2-to-1 margin.

In what would emerge as a recurring theme of segregationist resistance, these political leaders offered a drastic solution. Unwilling to let municipal spaces be integrated, they instead urged the city to abandon its public lands altogether. Talmadge, for instance, suggested the city sell its parks and playgrounds to private interests who could keep them white. The Supreme Court’s ruling, he predicted dourly, would “probably mean the end of most public golf courses, playgrounds, and things of that type.”

As whites abandoned the pools, they asked the city to follow suit. And in many ways, Atlanta did. The next summer, for instance, hours of operation were cut back at most public pools. The change had been made, Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. noted, “so as to lessen racial tension wherever possible.” But the city did more than simply reduce the operating hours of its pools; it also reduced their size and scope. Instead of the old system, in which large pools served broad sections of the city, Atlanta launched a new “neighborhood pool policy,” which relied on smaller “walk-to” pools enclosed in individual

...more

Their taxes were being used to fund services enjoyed largely by blacks. Whites refused to acknowledge that this was a result of their own racism, however, and instead blamed the city for “surrendering” these public spaces to blacks.42

Supposedly tax "victimization" of whites due to desegregation. Really, they caused it themselves; This is a similar argument from whites in Katherine Cramer.

On one side, Mayor Hartsfield and HOPE insisted that segregated education could never last and promised the “local option” approach could keep integration to token levels. On the other, segregationists in MASE and the state capitol stood by the private school plan, which they hoped would preserve segregation and education alike.