More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

March 30 - April 7, 2020

Mayor Ivan Allen Jr., who had recently replaced Hartsfield in office, had expected some backlash but was stunned by its intensity. From retirement, his predecessor offered a bit of belated advice: “Never make a mistake they can take a picture of.”2

local whites embraced the roadblocks as their salvation. The day after the crews sealed off their streets, residents wrapped the barricades in Christmas paper and ribbon; beneath the words “Road Closed,” someone added, “Thank the Lord!”

response to the “vicious, block-busting tactics being used by Negro realtors.” Carlton Owens, an engineer at Atlantic Steel and a member of Southwest Citizens’ board of directors, noted that several residents had said they were going to “sell and get out” if something concrete were not done “to stabilize the situation.”

Early Monday morning, construction crews sunk new beams into the scorched asphalt, attaching steel rails this time to prevent further fires. Just to make sure, small groups of robed Klansmen stood guard at the barricades on Monday and Tuesday night. Patrolling the street, they held aloft signs: “Whites Have Rights, Too.”

the barricades were destroyed, so was whites’ confidence in the neighborhood. In less than a month, most homes in Peyton Forest—including that of Virgil Copeland, the head of the homeowners’ resistance movement—were listed for sale with black real-estate agents. “When the barricades came down, everything collapsed,” he told a reporter. “It’s all over out there for us.” Indeed, by the end of July 1963 all but fifteen white families had sold their homes to black buyers and abandoned the neighborhood.

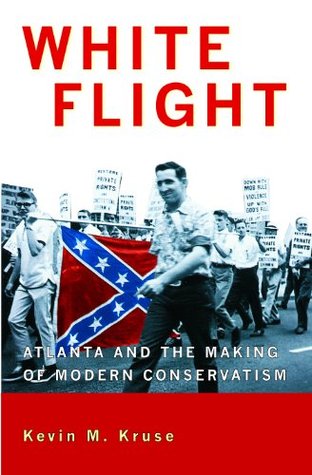

This study, however, seeks to explore not simply the effects of white flight, but the experience. While many have assumed that white flight was little more than a literal movement of the white population, this book argues that it represented a much more important transformation in the political ideology of those involved.

Because of their confrontation with the civil rights movement, white southern conservatives were forced to abandon their traditional, populist, and often starkly racist demagoguery and instead craft a new conservatism predicated on a language of rights, freedoms, and individualism.

helped southern conservatives dominate the Republican Party and, through it, national politics as well. White flight, in the end, was more than a physical relocation. It was a political revolution.

the struggle to defend the “southern way of life” stretched on.

Ultimately, the mass migration of whites from cities to the suburbs proved to be the most successful segregationist response to the moral demands of the civil rights movement and the legal authority of the courts.

white residents succeeded in convincing the courts, the nation, and even themselves that this phenomenon represented de facto segregation, something that stemmed not from the race-conscious actions of residents but instead from less offensive issues like class stratification and postwar sprawl.

on the surface, the world of white suburbia looked little like the world of white supremacy. But these worlds did have much in common—from the remarkably similar levels of racial, social, and political homogeneity to their shared ideologies that stressed individual rights over communal responsibilities, privatization over public welfare, and “free enterprise” above everything else.

By withdrawing to the suburbs and recreating its world there, the politics of massive resistance continued to thrive for...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

If we truly seek to understand segregationists—not to excuse or absolve them, but to understand them—then we must first understand how they understood themselves.

in their own minds, segregationists were instead fighting for rights of their own—such as the “right” to select their neighbors, their employees, and their children’s classmates, the “right” to do as they pleased with their private property and personal businesses, and, perhaps most important, the “right” to remain free from what they saw as dangerous encroachments by the federal government.

The true goal of desegregation, these white southerners insisted, was not to end the system of racial oppression in the South, but to install a new system that oppressed them instead. As this study demonstrates, southern whites fundamentally understood their support of segregation as a defense of their own liberties, rather than a denial of others’.18

In northern cities, the predominance of heavy industry helped move race relations in both progressive and reactionary directions. At first, the rise of biracial unions served as an early impetus for desegregation not simply on the shop floor but throughout the city. But as hard times fell on northern cities, the consequences of economic decline and deindustrialization—massive layoffs, plant closings, and industrial relocation to the suburbs—not only fueled white flight, but also served to splinter the unions and, in the process, the entire liberal-labor political alliance.

the South, with a few notable exceptions, the postwar urban struggle centered not on deindustrialization but desegregation.

the South, however, desegregation, especially in the schools, had tremendous influence during the 1950s and 1960s in reshaping cities and the course of white resistance within them. Desegregation of neighborhood schools impacted surrounding neighborhoods, of course, convincing white residents to sell their homes and leading community institutions to pull up roots.

As urban populations grew and rural ones shrank, the county unit system thus ensured that smaller counties wielded wildly disproportionate political power. (In 1946, for instance, 14,092 votes from Atlanta’s Fulton County carried precisely the same weight as 132 votes from rural Chattahoochee County.)

The disfranchisement of blacks and the county unit system ensured that Georgia’s politics would be dominated by the forces of rural racism for decades.

raw racism won Talmadge the overwhelming support of rural whites, which, through the county unit system, won him elections. By 1940 Gene Talmadge had been elected governor three times and commissioner of agriculture three more.

There was “no danger” that blacks would take part in Georgia’s politics, he announced, as long as the state Democratic Party maintained its whites-only primary.

April 1944, when the United States Supreme Court ruled in Smith v. Allwright that the white primary held by Texas Democrats was unconstitutional.

within a year’s time, both the poll tax and white primary had been struck down.

Speaking at a Ku Klux Klan rally in Atlanta, his son Herman asked, “Why should Nigras butt in and tell white people who should be elected in a white primary?” His father felt the same way and predicted the turn of events would lead to the end of white supremacy in the state. “With the white primary out of the way,” he told a Greensboro audience, “negroes will vote in numbers and repeal our laws requiring [segregation] in schools, hotels, and on trains—even those which prohibit intermarriage.” In his mind, the situation was serious but the solution simple. Asked how they might keep blacks away

...more

the county unit system proved crucial to Talmadge’s success. He lost the popular vote to opponent James Carmichael, 297,245 to 313,389, but dominated the county unit vote, 242 to 146.)

In western Taylor County, for instance, a black World War II veteran who dared to vote in the primary was dragged from his home and shot to death by four whites. Afterward, a sign was posted on a nearby black church: “The First Nigger to Vote Will Never Vote Again.”

two groups that regularly served as targets in Gene Talmadge’s stump speeches—blacks and urban moderates. Long scapegoated under the politics of rural racism,

After months of political maneuvering and preparation, eight black patrolmen joined the force in March 1948. But their employment came with a host of restrictions. Keeping with the customs of segregation, they operated out of a separate station, on a separate watch, and solely in the city’s black neighborhoods, where they were not allowed to arrest whites.

Robert Woodruff, played an undeniably important role in advancing desegregation in Atlanta. As late as 1960, however, he privately mocked civil rights laws as guaranteeing “the right of a chimpanzee to vote.”

John Sibley, chairman of the Trust Company of Georgia and a close friend of Woodruff’s, championed “‘natural segregation,’ a thing that all races with different cultural backgrounds and aspirations always seek.” In Sibley’s mind, school desegregation would assuredly result in a “mongrel race of lower ideals, lower standards, and lower traditions.”

As Hartsfield reminded blacks and whites alike, a black-majority city would be simply unworkable in the South. To Hartsfield and his allies, the solution was simple. Atlanta should annex the surrounding suburbs, thereby increasing its size and, more important, its white population.

he presented annexation as a way to bring “decent people”—middle-class whites—into the city. Hartsfield warned of the alternative:

Outmigration is good white, home owning citizens. With

our white citizens are just going to move out and give it to them.

do you want to hand them political control of Atlanta,

Atlanta, he told the crowd, was “a city too busy to hate.” To his delight, the nickname stuck. A few years later, Hartsfield explained what he meant. “We strive to undo the damage the Southern demagogue does to the South. We strive to make an opposite impression from that created by the loud-mouthed clowns. Our aim in life,” he concluded, “is to make no business, no industry, no educational or social organization ashamed of the dateline ‘Atlanta.’ ”43

Something of a semiprofessional fascist, Gewinner stood before the crowd as a featured speaker for the Columbians, the first neo-Nazi organization in Atlanta and, for that matter, the United States.

“The reason veterans cannot find housing,” Gewinner argued, “is that unscrupulous real estate dealers are selling white property to Negroes, thus forcing all whites in the neighborhood to move.”

“There are two ways to fight this thing,” he roared. “With ballots and with bullets! We are going to try ballots first!”

The pledge cards he distributed were short and simple. “I want the Columbians to continue the fight for the American white working man,” the signers swore. “I want the Columbians to continue the fight to effectively separate the white and black races.”

The end of World War II brought a severe housing crisis to Atlanta, as thousands of veterans returned home to discover the city had not only failed to build new homes during their absence but actually started to destroy old ones. Black leaders banded together to create new housing on the city’s outskirts, but found such projects blocked by local resistance and government red tape. In the end, they had only one option. “Following the pressure of increased population,” Atlanta’s Metropolitan Planning Commission observed, “their only avenue for expansion has been ‘encroachment’ into white

...more

segregationist groups sprang to life there in rapid succession—first the fascist Columbians, then a revived version of the Ku Klux Klan, and finally a homeowners’ group known as the West End Cooperative Corporation.

their careers still testify to an important evolution of segregationist organization and outreach.

segregationists relied on populist rhetoric and stark racism to harness the discontent of working-class whites.

In time, they would learn to put aside the brown shirts of the Columbians and the white sheets of the Klan and instead present themselves as simple homeowners and concerned citizens.

“Atlanta is the logical place to start something,” Loomis reasoned. “The South comes by its racial convictions instinctively.” Thus, in 1946 they founded the fascist Columbians there.

“We’re going to show the white Anglo-Saxons how to take control of the Government,” they told their associates. “We’re trying to show them they have power in their grasp if they’ll just organize and assert themselves!”

Enlisting was fairly easy. “There are just three requirements,” Loomis told prospects. “Number one: Do you hate niggers? Number two: Do you hate Jews? And three: Have you got three dollars?”