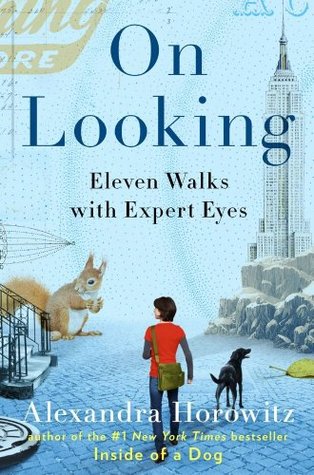

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

We see, but we do not see: we use our eyes, but our gaze is glancing, frivolously considering its object. We see the signs, but not their meanings. We are not blinded, but we have blinders.

One trouble with being human—with the human condition—is that, as with many conditions, you cannot turn it off.

I learned from my son how much happens when you are waiting for the thing that is supposed to be the big event.

humans are also, for the most part, predatory, disruptive, and destructive.

It had to do with how I was looking. Part of what restricts us seeing things is that we have an expectation about what we will see, and we are actually perceptually restricted by that expectation.

The sidewalk seems uninteresting and ahistorical, but this is borne of perceived familiarity. Sometimes we see least the things we see most.

The morning had seen rain but the afternoon had forgotten it.

“The only true voyage . . . would be not to visit strange lands but to possess other eyes, to see the universe through the eyes of another, of a hundred others, to see the hundred universes that each of them sees, that each of them is.” (Marcel Proust)

But it was the same space, the same block, the same city. I hoped that something had changed. The likeliest thing would be me.

Part of seeing what is on an ordinary block is seeing that everything visible has a history. It arrived at the spot where you found it at some time, was crafted or whittled or forged at some time, filled a certain role or existed for a particular function. It was touched by someone (or no one), and touches someone (or no one) now. It is evidence. The other part of seeing what is on the block is appreciating how limited our own view is. We are limited by our sensory abilities, by our species membership, by our narrow attention—at least the last of which can be overcome. We walk the same block

...more