More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 28 - December 30, 2023

Doe cases got the least coverage, even though they were the ones that needed it most. So,

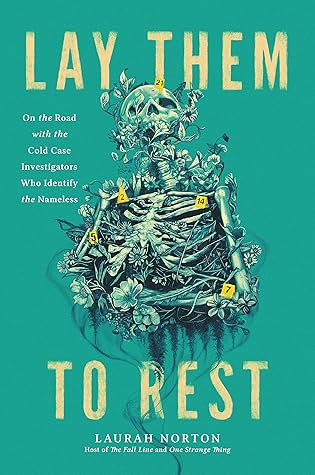

Many people are called to the cases of the unidentified: scientists of every discipline, artists, researchers, writers, genealogists, investigators, even podcasters.

More often, it’s the beginning of another mystery, another unspooling, the threads of a second investigation into a murder.

The official funding for Doe identification—which in turn solves at least some missing-persons cases—will never be high enough to meet the need.

In hiding what was left of the victim, Ina’s killer had essentially forced investigators to work in reverse: Take this awful crime and turn it back into a person.

Researchers found that 82.7 percent of these deaths were due to injuries. When I read injury, I thought accident—but no; that phrase included any mortal wound.

Among injury deaths counted in the study, 31.8 percent were officially classified as homicides.

But there are people whose disappearances are never actually reported—the “un-missing,” as a forensic anthropologist once described to me—who likely make the numbers harder to calculate.

Unique physical characteristics can be key in identification, too, though they can also spark misidentifications, or even complex theories that ultimately lead to dead ends; perhaps that’s because of our need to create cause where there is only suggestion.

Nothing is static, she typed. Not even bones.

Cases were supposed to stay in their own little category and be put away when we stopped working. Everyone knew that wasn’t possible, but the pretense was kept up.

crime historian Harold Schechter termed “the golden age of serial murder.”

Now a term I’m more familiar with, from college: anthropology: “the study of the human race, especially of its origins, development, customs, and beliefs.”

Most people I’ve met in the anthropological space understand the dead because they care about the living—and know that none of us, when we die, exist as a set of bones, devoid of context.

Hanging out with them is a more accurate term for it, really, since there’s a lot of bad television involved in our downtime, and eating junk food in hotel rooms, and for some reason, they really love going to oddity shops and cryptid museums and taking group photos in front of things like the World’s Biggest Shoe—no idea why we had to see that, thinking back—but anyway, it’s been enlightening.

Anthropologists want to understand people, after all.

What I’ve picked up, more than anything, is that the field of anthropology is dynamic, and holistic, and comparative.

how much identity plays a role in reidentification after death.

“Blinded by the White: Forensic Anthropology and Ancestry Estimation,” on YouTube,

Academics come in two flavors: neat and armed with expensive pens they special ordered, and well-meaning human whirlwinds who accidentally got hair dye or coffee on student papers and had to note not blood in the margins. Amy

Suddenly, they were all putting on gloves. Anthropologists always seem to somehow have pairs everywhere, like magicians pulling those colorful ropes of scarves out of every pocket.

Interpreting is the key word here: There are so many choices a forensic artist must make.

Karen Taylor is perhaps the most influential forensic artist in the United States. Maybe in the world. I spot her book, Forensic Art and Illustration, in the office of every forensic artist I meet. Some anatomical artists, too.

I could hear the smile in Ann Marie’s voice, which sounds like an untrue thing that people tell you, until you’ve done a lot of phone interviews. You really can begin to discern expressions just from sound.

Names were important, after all. They were the key to everything.

Because there’s always a chance. And because we don’t like to give up. Not without a lot of fight.