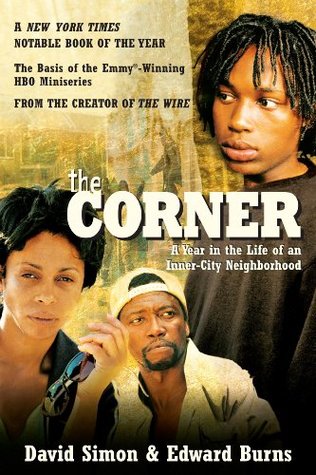

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

David Simon

Read between

September 4 - October 3, 2021

The sad and beautiful truth about Gary McCullough—a man born and raised in as brutal and unforgiving a ghetto as America ever managed to create—is that he can’t bring himself to hurt anyone.

Today, he is free to hail a right-living young man who transcended the corners to serve his country and, ultimately, to give his life not to a needle or handgun, but to the random chance of a loose electrical cable. In Baltimore, this is close enough to be called victory.

the dealers and fiends have won because they are legion. They’ve won because the state of Maryland and the federal government have imprisoned thousands and arrested tens of thousands and put maybe a hundred thousand on the parole and probation rolls—and still it isn’t close to enough. By raw demographics, the men and women of the corners can claim victory. In Baltimore alone—a city of fewer than seven hundred thousand souls, with some of the highest recorded rates of intravenous drug use in the nation—they are fifty, perhaps even sixty thousand strong—three of them for every available prison

...more

Worse still, the absence of a real deterrent has bred a stupidity in the new school that is, for lack of a better word, profound.

You carry it like it means nothing, telling yourself the old prison-tier lie that says you really only do two days—the day you go in and the day you come out.

Once, a stickup boy could go into battle relying at least on the organizational structure; they knew who they were going up against and the consequence of those actions. But today, when even fifteen-year-old hoppers have a loaded .380 hidden in the alley, the job is little better than a death wish.

“Sheeeet,” says Curt,

the right word to the wrong person would get your ass shot up.

He fashioned the street name himself, figuring that any real gangster ought to be able to fashion his own corner legend, rather than leaving such important matters to random chance.

Tonight, they’ve snatched a good and ordinary time from the streets of a sad and extraordinary place.

DeAndre can’t often be trusted, but the bureaucrats can’t be trusted at all.

In the end, the only rumor with any truth in it is the one that always follows a death on the needle: When the fiends along Fayette Street hear that Bread had succumbed to a blast of coke, they all, quite naturally, want to know who is selling the shit.

And so, the corner gives up its dead to an empty funeral parlor, with Bread Corbett laid out in a Sunday pinstripe for his mother and a handful of other family members.

This is a truth once understood by any cop worth his pension—if you’re policing an Amish town and the worst crime is spitting on the sidewalk, then enforce that law. But if you’re policing Baltimore or a city like it, and the worst crimes are murder, rape, armed robbery and aggravated assault, then don’t waste your time, men, and money throwing gin-breathed wrecks into a police wagon.

Just say no. We threw a negative at them, though it’s unclear what they’re supposed to say yes to on Fayette Street.

For Mike, this is a last chance. If he stays on Fayette Street, he’ll surely sling drugs, and he’ll just as surely end up shooting the next fiend who tries to rob him. Mike has too much heart not to shoot.

The business sense buried deep in Gary’s soul has to smile at it: all of us ants working for the king, all of this damage being done so that the Metal King can live large. Whoever he is and wherever he lives, the King is a bold one, worthy of admiration.

A swirl of the scavenging birds is hovering above, waiting their turn. But the gulls lose out; Gary and Tony are now in the baked goods business.

Gary watches as two bills—a five and a one—come up after the papers and float silently to the linoleum floor. The deacon is oblivious. Gary doesn’t hesitate. “Ho,” he says, reaching down, “you dropped your money.”

this is Fran Boyd’s plan—linear and fixed in the same way that every dope fiend’s plan ever is. I’ll do A and B and then get someone’s permission to do C so that I’ll qualify for D. If at any point something doesn’t come through, the whole enterprise comes crashing down and the fiend goes back to the nearest corner. If the judge doesn’t let Mike off probation, he’s off the ship and back to shooting people. If DeAndre doesn’t get hired at the McDonald’s, he’ll be back with the rest of his crew, slinging down on Fairmount. And if Fran doesn’t get into BRC, she’ll stay on the stoop of the Dew

...more

He went home and got the big gun, the four-four. Then he walked back down to the mouth of the Vine Street alley where he waited in deadly earnest for the dealer to return. But the man did not come back, and the next afternoon, Mike Ellerbee was in a window seat, looking down at the Atlantic. That was the real story. That was the plan—thin, precarious, and in the end, more a twist of fate than anything else.

ninety-nine times out of a hundred, the thing ends with traded insults and maybe an unkept promise to come back with a gun or an older brother or the rest of whatever corner crew is involved. The hundredth time someone comes back in the worst way, but that’s what the corner is about.

He goes back up Fayette Street on that wet, clouded afternoon in May with a tale of bona fide achievement, but precious few people with whom he can share it.

Take the entire Phillips Exeter Academy, drop it into West Baltimore, and fill its ivy-covered campus with DeAndre McCulloughs, Richard Carters, and four hundred of their running buddies, and see just how little can be had for a dollar’s worth of education.

the drugs will not disappear in a culture where everything else—jobs, money, hope, meaning—has already vanished.

the number of those actually deserving promotion is appallingly low. But next year, there will be another swarm of eighth-graders. And they can’t be taught if a third of last year’s class is hulking in the back of the room. “Gregg.” “His stepfather got him working.” “Pass.” What is left at the end of such an exercise is a school system playing with numbers in the same way that the police department must, a bureaucracy still seeking some proportional response to a problem of complete disproportion.

Others might find it in themselves to bow to authority, to accept the bargain and conform, but by and large, those people have a basic allegiance to the predominant culture, and DeAndre McCullough knows no such allegiance. The world can make no legitimate demands because the world hasn’t done shit for him these sixteen years; he lives on Fayette Street.

In another time and place, the damned were shot and gassed and burned by the millions with frightening efficiency. In West Baltimore, in a nation of civil liberties, there was instead the slow-motion destruction of thousands. It was different, Gary had to admit; but it was the same, too.

Times like these, a crab-slinger will hurl the assailant against a wall. Crab fission, Mo, and leave the debris there on the ground as a warning to others. But not Gary. “Hey, hey,” he says, dropping the crab gently into the pot. “Crab got his job to do. I got mine.”

Check day’s effect on open-air markets like Mount and Fayette makes clear the economic role of the welfare dollar in the drug culture.

The cash money goes first—the AFDC dollars, the SSI checks, the DALP money—but at the end of the week, the food stamps are being traded for eighty or sixty or fifty cents on the dollar.

all told, what we’re spending on the poor constitutes a thin share of what the government spends in total—less than three percent of federal and state spending overall. In the grand scheme of government, all of it added up and compounded with interest is hardly worth complaining about, yet incredibly, we are forever complaining. Absurd as such an expectation is, the belief that all of our handouts will at some point produce viable citizens remains with us; when nothing of the sort comes to pass, we are furious.

Cut the flow of government dollars, and the capers and dope-fiend moves will become more desperate; the corner violence will intensify and the assault rate will jump and the bleeders will begin washing up at the emergency rooms in waves. And more hustles mean more lockups, which means more cops, judges, lawyers, jail guards, and probation officers. More prisons, too—that’s the ultimate in societal cost, to the tune of an additional thirty thousand dollars or more annually to take hold of a solitary shoplifter or half-dead tout.

End welfare, or curtail it, or replace it with some crude carrot-and-stick approximation of workfare and the result is unpredictable. What passes for welfare reform will surely provoke some people to lift themselves up and escape the dole. But for the rest, it will likely solve nothing, and make the cities less livable than they already are. When the money dries up on Fayette Street, the corners will reach out and take their share from the next neighborhood over, and the next after that, until a problem that once seemed distant becomes a collision of worlds.

A soldier to the core, Fat Curt refuses to die and refuses to get well; it therefore occurs to those overseeing his medical adventure that it might be better to deposit him somewhere else in the city than to have him show up in the same emergency room yet again.

Much was said by the pastor, some of it quite true.