More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

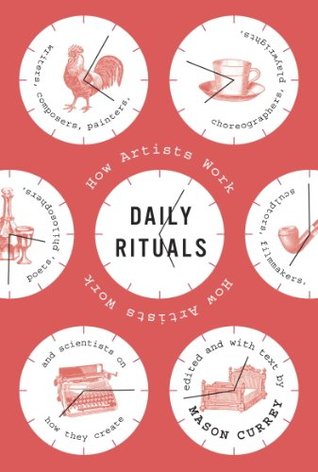

The book’s title is Daily Rituals, but my focus in writing it was really people’s routines. The word connotes ordinariness and even a lack of thought; to follow a routine is to be on autopilot. But one’s daily routine is also a choice, or a whole series of choices. In the right hands, it can be a finely calibrated mechanism for taking advantage of a range of limited resources: time (the most limited resource of all) as well as willpower, self-discipline, optimism. A solid routine fosters a well-worn groove for one’s mental energies and helps stave off the tyranny of moods.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Beethoven rose at dawn and wasted little time getting down to work. His breakfast was coffee, which he prepared himself with great care—he determined that there should be sixty beans per cup, and he often counted them out one by one for a precise dose. Then he sat at his desk and worked until 2:00 or 3:00, taking the occasional break to walk outdoors, which aided his creativity.

Voltaire (1694–1778)

A visitor recorded Voltaire’s routine in 1774: He spent the morning in bed, reading and dictating new work to one of his secretaries. At noon he rose and got dressed. Then he would receive visitors or, if there were none, continue to work, taking coffee and chocolate for sustenance. (He did not eat lunch.) Between 2:00 and 4:00, Voltaire and his principal secretary, Jean-Louis Wagnière, went out in a carriage to survey the estate. Then he worked again until 8:00, when he would join his widowed niece (and longtime lover) Madame Denis and others for supper. But his working day did not end there.

...more

Jane Austen (1775–1817)

Nevertheless, between settling in Chawton in 1809 and her death, Austen was remarkably productive: she revised earlier versions of Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice for publication, and wrote three new novels, Mansfield Park, Emma, and Persuasion. Austen wrote in the family sitting room, “subject to all kinds of casual interruptions,” her nephew recalled. She was careful that her occupation should not be suspected by servants, or visitors, or any persons beyond her own family party. She wrote upon small sheets of paper which could easily be put away, or covered with a piece of

...more

Austen rose early, before the other women were up, and played the piano. At 9:00 she organized the family breakfast, her one major piece of household work. Then she settled down to write in the sitting room, often with her mother and sister sewing quietly nearby. If visitors showed up, she would hide her papers and join in the sewing. Dinner, the main meal of the day, was served between 3:00 and 4:00. Afterward there was conversation, card games, and tea. The evening was spent reading aloud from novels, and during this time Austen would read her work-in-progress to her family. Although she did

...more

Ernest Hemingway

When I am working on a book or a story I write every morning as soon after first light as possible. There is no one to disturb you and it is cool or cold and you come to your work and warm as you write. You read what you have written and, as you always stop when you know what is going to happen next, you go on from there. You write until you come to a place where you still have your juice and know what will happen next and you stop and try to live through until the next day when you hit it again. You

he did have his share of writing idiosyncrasies. He wrote standing up, facing a chest-high bookshelf with a typewriter on top, and on top of that a wooden reading board. First drafts were composed in pencil on onionskin typewriter paper laid slantwise across the board; when the work was going well, Hemingway would remove the board and shift to the typewriter. He tracked his daily word output on a chart—“so as not to kid myself,” he said. When the writing wasn’t going well, he would often knock off the fiction and answer letters, which gave him a welcome break from “the awful responsibility of

...more

F. Scott Fitzgerald

When he enlisted in the army in 1917 and was sent to training camp in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, the barely twenty-one-year-old Princeton dropout composed a 120,000-word novel in only three months.

But in his post-military writing life, Fitzgerald always had trouble sticking to a regular schedule. Living in Paris in 1925, he generally rose at 11:00 A.M. and tried to start writing at 5:00 P.M., working on and off until 3:30 in the morning. In reality, however, many of his nights were spent on the town, making the rounds of the cafés with Zelda. The real writing usually happened in brief bursts of concentrated activity, during which he could manage seven thousand or eight thousand words in one session. This method worked pretty well for short stories, which Fitzgerald preferred to compose

...more

Fitzgerald increasingly believed that alcohol was essential to his creative process. (He preferred straight gin—it worked fast and was, he thought, difficult to detect on one’s breath.)

Toni Morrison (b. 1931)

“I am not able to write regularly,” Morrison told The Paris Review in 1993. “I have never been able to do that—mostly because I have always had a nine-to-five job. I had to write either in between those hours, hurriedly, or spend a lot of weekend and predawn time.”

“I am not very bright or very witty or very inventive after the sun goes down.” For the morning writing, her ritual is to rise around 5:00, make coffee, and “watch the light come.” This last part is crucial. “Writers all devise ways to approach that place where they expect to make the contact, where they become the conduit, or where they engage in this mysterious process,” Morrison said. “For me, light is the signal in the transaction. It’s not being in the light, it’s being there before it arrives. It enables me, in some sense.”

Joyce Carol Oates (b. 1938)

“I write and write and write, and rewrite, and even if I retain only a single page from a full day’s work, it is a single page, and these pages add up,”

“Getting the first draft finished is like pushing a peanut with your nose across a very dirty floor.”

Chuck Close (b. 1940)

“Inspiration is for amateurs,” Close says. “The rest of us just show up and get to work.”

Nicholson Baker (b. 1957)

But there’s something to just the excitement of coming up with a slightly different routine. I find I have to do it for each book, have something different.” While he was writing his first book, The Mezzanine, Baker worked a series of office jobs in Boston and New York. Then his routine was to write on his lunch break, taking advantage of this “pure, blissful hour of freedom” in the middle of the day to make notes for a novel that was, appropriately, about an office drone returning to work from his lunch hour. Later, Baker worked a job outside of Boston that required a ninety-minute commute,

...more

B. F. Skinner (1904–1990)

The founder of behavioral psychology treated his daily writing sessions much like a laboratory experiment, conditioning himself to write every morning with a pair of self-reinforcing behaviors: he started and stopped by the buzz of a timer, and he carefully plotted the number of hours he wrote and the words he produced on a graph.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

In his daily habits, at least, he was not given to self-control or even much regularity. Left to his own devices, Joyce would typically rise late in the morning and use the afternoon (when, he said, “the mind is at its best”) to write or to fulfill whatever professional obligations he might be under—often, teaching English or giving piano lessons to pay the bills. His evenings were spent socializing at cafés or restaurants, and they sometimes ended early the next morning with Joyce, who was proud of his tenor singing voice, belting out old Irish songs at the bar.

By 1914 he had begun Ulysses, and then he worked indefatigably on the book every day—although he still stuck to his preferred schedule of writing in the afternoons and staying out late drinking with friends. He felt he needed the nightly breaks to clear his head from literary labor that was exacting and exhausting. (Once, after two days of work yielded only two finished sentences, Joyce was asked if he had been seeking the right words. “No,” he replied, “I have the words already. What I am seeking is the perfect order of words in the sentences I have.”) Joyce finally finished the book in

...more

Jean-Paul Sartre

“Three hours in the morning, three hours in the evening. This is my only rule.”

Sartre lived in a creative frenzy for most of his life, alternating between his daily six hours of work and an intense social life filled with rich meals, heavy drinking, drugs, and tobacco.

At night he slept badly, knocking himself out for a few hours with barbiturates.

Rather than slow down, however, he turned to Corydrane, a mix of amphetamine and aspirin then fashionable among Parisian students, intellectuals, and artists (and legal in France until 1971, when it was declared toxic and taken off the market). The prescribed dose was one or two tablets in the morning and at noon. Sartre took twenty a day, beginning with his morning coffee and slowly chewing one pill after another as he worked. For each tablet, he could produce a page or two of his second major philosophical work, The Critique of Dialectical Reason. This was hardly his only excess. The

...more

Agatha Christie

I never had a definite place which was my room or where I retired specially to write.”

Somerset Maugham

He wrote for three or four hours every morning, setting himself a daily requirement of one thousand to one thousand five hundred words. He would get a start on the day’s work before he even sat down at his desk, thinking of the first two sentences he wanted to write while soaking in the bath. Then, once at work, there was little to distract him—Maugham believed that it was impossible to write while looking at a view, so his desk always faced a blank wall.

Maya Angelou (b. 1928)

Angelou has never been able to write at home. “I try to keep home very pretty,” she has said, “and I can’t work in a pretty surrounding. It throws me.” As a result, she has always worked in hotel or motel rooms, the more anonymous the better. She described her routine in a 1983 interview: I usually get up at about 5:30, and I’m ready to have coffee by 6, usually with my husband. He goes off to his work around 6:30, and I go off to mine. I keep a hotel room in which I do my work—a tiny, mean room with just a bed, and sometimes, if I can find it, a face basin. I keep a dictionary, a Bible, a

...more

Truman Capote

“I am a completely horizontal author,” Capote told The Paris Review in 1957. “I can’t think unless I’m lying down, either in bed or stretched out on a couch and with a cigarette and coffee handy. I’ve got to be puffing and sipping.

Capote typically wrote for four hours during the day, then revised his work in the evenings or the next morning, eventually doing two longhand versions in pencil before typing up a final copy. (Even the typing was done in bed, with the typewriter balanced on his knees.)

Writing in bed was the least of Capote’s superstitions. He couldn’t allow three cigarette butts in the same ashtray at once, and if he was a guest at someone’s house, he would stuff the butts in his pocket rather than overfill the tray. He couldn’t begin or end anything on a Friday. And he compulsively added numbers in his head, refusing to dial a telephone number or accept a hotel room if the digits made a sum he considered unlucky. “It’s endles...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Joseph Heller (1923–1999)

Heller wrote Catch-22 in the evenings after work, sitting at the kitchen table in his Manhattan apartment. “I spent two or three hours a night on it for eight years,” he said.

Heller wrote in longhand on yellow legal pads and reworked passages carefully, often numerous times—by hand and then on a typewriter—before handing them off to a typist for a final copy. “I am a chronic fiddler,” he said. While working, he liked to listen to classical music, particularly Bach. And if he skipped a day, he didn’t beat himself up. “It’s an everyday thing, but I’m never guilt-ridden if I don’t work,” he said. “I don’t have a compulsion to write, and I never have. I have a wish, an ambition to write, but it’s not one that justifies the word ‘drive.’ ” Neither was he insecure about

...more

William Styron

“Let’s face it, writing is hell,” Styron told The Paris Review in 1954. “I get a fine warm feeling when I’m doing well, but that pleasure is pretty much negated by the pain of getting started each day.”