More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

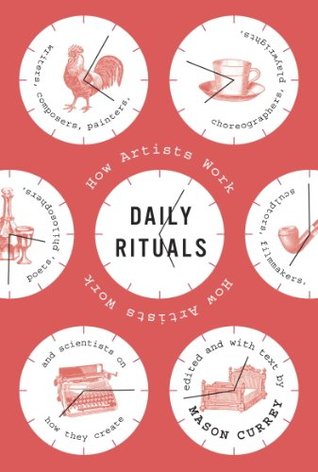

this is a superficial book. It’s about the circumstances of creative activity, not the product; it deals with manufacturing rather than meaning. But it’s also, inevitably, personal. (John Cheever thought that you couldn’t even type a business letter without revealing something of your inner self—isn’t that the truth?) My underlying concerns in the book are issues that I struggle with in my own life: How do you do meaningful creative work while also earning a living? Is it better to devote yourself wholly to a project or to set aside a small portion of each day? And when there doesn’t seem to

...more

The book’s title is Daily Rituals, but my focus in writing it was really people’s routines. The word connotes ordinariness and even a lack of thought; to follow a routine is to be on autopilot. But one’s daily routine is also a choice, or a whole series of choices. In the right hands, it can be a finely calibrated mechanism for taking advantage of a range of limited resources: time (the most limited resource of all) as well as willpower, self-discipline, optimism. A solid routine fosters a well-worn groove for one’s mental energies and helps stave off the tyranny of moods. This was one of

...more

For every cheerfully industrious Gibbon who worked nonstop and seemed free of the self-doubt and crises of confidence that dog us mere mortals, there is a William James or a Franz Kafka, great minds who wasted time, waited vainly for inspiration to strike, experienced torturous blocks and dry spells, were racked by doubt and insecurity. In reality, most of the people in this book are somewhere in the middle—committed to daily work but never entirely confident of their progress; always wary of the one off day that undoes the streak. All of them made the time to get their work done. But there is

...more

I often thought of a line from a letter Kafka sent to his beloved Felice Bauer in 1912. Frustrated by his cramped living situation and his deadening day job, he complained, “time is short, my strength is limited, the office is a horror, the apartment is noisy, and if a pleasant, straightforward life is not possible then one must try to wriggle through by subtle maneuvers.”

Auden believed that a life of such military precision was essential to his creativity, a way of taming the muse to his own schedule. “A modern stoic,” he observed, “knows that the surest way to discipline passion is to discipline time: decide what you want or ought to do during the day, then always do it at exactly the same moment every day, and passion will give you no trouble.”

(He was dismissive of night owls: “Only the ‘Hitlers of the world’ work at night; no honest artist does.”)

To maintain his energy and concentration, the poet relied on amphetamines, taking a dose of Benzedrine each morning the way many people take a daily multivitamin. At night, he used Seconal or another sedative to get to sleep. He continued this routine—“the chemical life,” he called it—for twenty years, until the efficacy of the pills finally wore off. Auden regarded amphetamines as one of the “labor-saving devices” in the “mental kitchen,” alongside alcohol, coffee, and tobacco—although he was well aware that “these mechanisms are very crude, liable to injure the cook, and constantly breaking

...more

Fellini wrote for newspapers as a young man, but he found that his temperament was better suited to the movies—he liked the sociability of the filmmaking process. “A writer can do everything by himself—but he needs discipline,” he said. “He has to get up at seven in the morning, and be alone in a room with a white sheet of paper. I am too much of a vitellone [loafer] to do that. I think I have chosen the best medium of expression for myself. I love the very precious combination of work and of living-together that filmmaking offers.”

But even after he retired from filmmaking in 1982, Bergman continued to make television movies, direct plays and operas, and write plays, novels, and a memoir. “I have been working all the time,” he said, “and it’s like a flood going through the landscape of your soul. It’s good because it takes away a lot. It’s cleansing. If I hadn’t been at work all the time, I would have been a lunatic.”

When he did find the time to compose, Feldman employed a strategy that John Cage taught him—it was “the most important advice anybody ever gave me,” Feldman told a lecture audience in 1984. “He said that it’s a very good idea that after you write a little bit, stop and then copy it. Because while you’re copying it, you’re thinking about it, and it’s giving you other ideas. And that’s the way I work. And it’s marvelous, just wonderful, the relationship between working and copying.”

Beethoven rose at dawn and wasted little time getting down to work. His breakfast was coffee, which he prepared himself with great care—he determined that there should be sixty beans per cup, and he often counted them out one by one for a precise dose.

After a midday dinner, Beethoven embarked on a long, vigorous walk, which would occupy much of the rest of the afternoon. He always carried a pencil and a couple of sheets of music paper in his pocket, to record chance musical thoughts. As the day wound down, he might stop at a tavern to read the newspapers. Evenings were often spent with company or at the theater, although in winter he preferred to stay home and read. Supper was usually a simple affair—a bowl of soup, say, and some leftovers from dinner. Beethoven enjoyed wine with his food, and he liked to have a glass of beer and a pipe

...more

Kierkegaard had his own quite peculiar way of having coffee: Delightedly he seized hold of the bag containing the sugar and poured sugar into the coffee cup until it was piled up above the rim. Next came the incredibly strong, black coffee, which slowly dissolved the white pyramid. The process was scarcely finished before the syrupy stimulant disappeared into the magister’s stomach, where it mingled with the sherry to produce additional energy that percolated up into his seething and bubbling brain—which in any case had already been so productive all day that in the half-light Levin could

...more

In his Autobiography, Franklin famously outlined a scheme to achieve “moral perfection” according to a thirteen-week plan. Each week was devoted to a particular virtue—temperance, cleanliness, moderation, et cetera—and his offenses against these virtues were tracked on a calendar. Franklin thought that if he could maintain his devotion to one virtue for an entire week, it would become a habit; then he could move on to the next virtue, successively making fewer and fewer offenses (indicated on the calendar by a black mark) until he had completely reformed himself and would thereafter need only

...more

Freud’s long workdays were mitigated by two luxuries. First, there were his beloved cigars, which he smoked continually, going through as many as twenty a day from his mid-twenties until near the end of his life, despite several warnings from doctors and the increasingly dire health problems that dogged him throughout his later years. (When his seventeen-year-old nephew once refused a cigarette, Freud told him, “My boy, smoking is one of the greatest and cheapest enjoyments in life, and if you decide in advance not to smoke, I can only feel sorry for you.”) Equally important, no doubt, were

...more

At Bollingen, Jung rose at 7:00 A.M.; said good morning to his saucepans, pots, and frying pans; and “spent a long time preparing breakfast, which usually consisted of coffee, salami, fruits, bread and butter,” the biographer Ronald Hayman notes. He generally set aside two hours in the morning for concentrated writing. The rest of his day would be spent painting or meditating in his private study, going for long walks in the hills, receiving visitors, and replying to the never-ending stream of letters that arrived each day. At 2:00 or 3:00 he took tea; in the evening he enjoyed preparing a

...more

In reality, Alma was not quite so sanguine about her new station as dutiful wife to a moody, solitary artist. (Prior to their marriage, she had been a promising composer in her own right, but Mahler had made her quit, saying that there could be only one composer in the family.) As she wrote in her diary that July, “There’s such a struggle going on in me! And a miserable longing for someone who thinks OF ME, who helps me to find MYSELF! I’ve sunk to the level of a housekeeper!”

When he is writing a novel, Murakami wakes at 4:00 A.M. and works for five to six hours straight. In the afternoons he runs or swims (or does both), runs errands, reads, and listens to music; bedtime is 9:00. “I keep to this routine every day without variation,” he told The Paris Review in 2004. “The repetition itself becomes the important thing; it’s a form of mesmerism. I mesmerize myself to reach a deeper state of mind.”

For the morning writing, her ritual is to rise around 5:00, make coffee, and “watch the light come.” This last part is crucial. “Writers all devise ways to approach that place where they expect to make the contact, where they become the conduit, or where they engage in this mysterious process,” Morrison said. “For me, light is the signal in the transaction. It’s not being in the light, it’s being there before it arrives. It enables me, in some sense.”

Given the number of hours she spends at the desk, Oates has pointed out, her productivity is not really so remarkable. “I write and write and write, and rewrite, and even if I retain only a single page from a full day’s work, it is a single page, and these pages add up,” she told one interviewer. “As a result I have acquired the reputation over the years of being prolix when in fact I am measured against people who simply don’t work as hard or as long.” This doesn’t mean that she always finds the work pleasant or easy; the first several weeks of a new novel, Oates has said, are particularly

...more

“Inspiration is for amateurs,” Close says. “The rest of us just show up and get to work.”

B. F. Skinner (1904–1990) The founder of behavioral psychology treated his daily writing sessions much like a laboratory experiment, conditioning himself to write every morning with a pair of self-reinforcing behaviors: he started and stopped by the buzz of a timer, and he carefully plotted the number of hours he wrote and the words he produced on a graph.

Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) The eighteenth-century preacher and theologian—a key figure in the Great Awakening and the author of the sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God”—spent thirteen hours a day in his study, beginning at 4:00 or 5:00 in the morning. (He noted in his diary, “I think Christ has recommended rising early in the morning, by his rising from the grave very early.”)

As for the extreme fixity of this regimen, this did not develop until the philosopher reached his fortieth birthday, and then it was an expression of his unique views on human character. Character, for Kant, is a rationally chosen way of organizing one’s life, based on years of varied experience—indeed, he believed that one does not really develop a character until age forty. And at the core of one’s character, he thought, were maxims—a handful of essential rules for living that, once formulated, should be followed for the rest of one’s life. Alas, we do not have a written list of Kant’s

...more

This routine was as follows: Kant rose at 5:00 A.M., after being woken by his longtime servant, a retired soldier under explicit orders not to let the master oversleep. Then he drank one or two cups of weak tea and smoked his pipe. According to Kuehn, “Kant had formulated the maxim for himself that he would smoke only one pipe, but it is reported that the bowls of his pipes increased considerably in size as the years went on.” After this period of meditation, Kant prepared his day’s lectures and did some writing. Lectures began at 7:00 A.M. and lasted until 11:00. His academic duties

...more

William James (1842–1910) In April 1870, a twenty-eight-year-old James made a cautionary note to himself in his diary. “Recollect,” he wrote, “that only when habits of order are formed can we advance to really interesting fields of action—and consequently accumulate grain on grain of wilful choice like ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The importance of forming such “habits of order” later became one of James’s great subjects as a psychologist. In one of the lectures he delivered to teachers in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1892—and eventually incorporated into his book Psychology: A Briefer Course—James argued that the “great thi...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The more of the details of our daily life we can hand over to the effortless custody of automatism, the more our higher powers of mind will be set free for their own proper work. There is no more miserable human being than one in whom nothing is habitual but indecision, and for whom the lighting of every cigar, the drinking of every cup, the time of rising and going to bed every day, and the beginning of every bit of work, are subjects of express volitional deliberation.

James was writing from personal experience—the hypothetical sufferer is, in fact, a thinly disguised description of himself. For James kept no regular schedule, was chronically indecisive, and lived a disorderly, unsettled life. As Robert D. Richardson wrote in his 2006 biography, “James on habit, then, is not the smug advice of some martinet, but the too-late-learned too-little-self-knowing, pathetically earnest, hard-won crumbs of practical advice offered by a man who really had no habits—or who lacked the habits he most needed, having only the habit of having no habits—and whose life was

...more

Henry James (1843–1916) Unlike his restless, compulsive older brother, Henry James always maintained regular working habits. He wrote every day, beginning in the morning and usually ending at about lunchtime. In his later years, severe wrist pain forced him to abandon his pen for dictation to a secretary, who would arrive each day at 9:30 A.M. After dictating all morning, James would read in the afternoon, have tea, go for a walk, eat dinner, and spend the evening making notes for the next day’s work. (For a while he asked one of his secretaries to return in the evenings for further dictation;

...more

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) “I get up at about eight, do physical exercises, then work without a break from nine till one,” Stravinsky told an interviewer in 1924. Generally, three hours of composition were the most he could manage in a day, although he would do less demanding tasks—writing letters, copying scores, practicing the piano—in the afternoon.

In Paris, Satie visited friends or arranged to meet them in cafés. He would also work on his compositions in cafés, but never in restaurants—Satie was a gourmet, and he eagerly looked forward to the evening meal. (Although he appreciated fine food and was meticulous in his tastes, Satie could also apparently eat in tremendous quantities; he once consumed a thirty-egg omelet in a single sitting.)

The scholar Roger Shattuck once proposed that Satie’s unique sense of musical beat, and his appreciation of “the possibility of variation within repetition,” could be traced to this “endless walking back and forth across the same landscape day after day.”

By the 1950s, too much work on too little sleep—with too much wine and cigarettes—had left Sartre exhausted and on the verge of collapse. Rather than slow down, however, he turned to Corydrane, a mix of amphetamine and aspirin then fashionable among Parisian students, intellectuals, and artists (and legal in France until 1971, when it was declared toxic and taken off the market). The prescribed dose was one or two tablets in the morning and at noon. Sartre took twenty a day, beginning with his morning coffee and slowly chewing one pill after another as he worked. For each tablet, he could

...more

The biographer Annie Cohen-Solal reports, “His diet over a period of twenty-four hours included two packs of cigarettes and several pipes stuffed with black tobacco, more than a quart of alcohol—wine, beer, vodka, whisky, and so on—two hundred milligrams of amphetamines, fifteen grams of aspirin, several grams of barbiturates, plus coffee, tea, rich meals.”

Dmitry Shostakovich (1906–1975) Shostakovich’s contemporaries do not recall seeing him working, at least not in the traditional sense. The Russian composer was able to conceptualize a new work entirely in his head, and then write it down with extreme rapidity—if uninterrupted, he could average twenty or thirty pages of score a day, making virtually no corrections as he went. “I always found it amazing that he never needed to try things out on the piano,” his younger sister recalled. “He just sat down, wrote out whatever he heard in his head, and then played it through complete on the piano.”

...more

He would play football and fool around with friends; then he would suddenly disappear. After forty minutes or so he would turn up again. “How are you doing? Let me kick the ball.” Then we would have dinner and drink some wine and take a walk, and he would be the life and soul of the party. Every now and then he would disappear for a while and then join us again. Towards the end of my stay, he disappeared altogether. We didn’t see him for a week. Then he turned up, unshaven and looking exhausted.

“Almost every morning for the next five years, he’d put on his only suit and ride the elevator with other men leaving for work; Cheever, however, would proceed all the way down to a storage room in the basement, where he’d doff his suit and write in his boxers until noon, then dress again and ascend for lunch.”

The German poet, historian, philosopher, and playwright kept a drawer full of rotting apples in his workroom; he said that he needed their decaying smell in order to feel the urge to write.

One of his pupils described Liszt’s routine: He rose at four every morning, even when he had been invited out the previous evening, had drunk a good deal of wine and not got to bed until very late. Soon after rising, and without breakfasting, he went to church. At five he took coffee with me, and with it a couple of dry rolls. Then work began: letters were written or read through, music tried out, and much else. At eight came the post, always bringing a huge pile of items. These were then looked through, personal letters read and answered, or music tried out.… At one o’clock, lunch was brought

...more

A younger colleague once asked Liszt why he didn’t keep a diary. “To live one’s life is hard enough,” he replied. “Why write down all the misery? It would resemble nothing more than the inventory of a torture chamber.”

Sand’s persona was larger than life—there’s the famous cross-dressing, the assumption of a male pen name, her numerous affairs with both men and women—but her work habits were fairly austere. She liked to nibble on chunks of chocolate at her desk, and she required regular doses of tobacco (cigars or hand-rolled cigarettes) to stay alert. But she did not subscribe to the idea of the drug-addled artist.

Inspiration can pass through the soul just as easily in the midst of an orgy as in the silence of the woods, but when it is a question of giving form to your thoughts, whether you are secluded in your study or performing on the planks of a stage, you must be in total possession of yourself.

Balzac drove himself relentlessly as a writer, motivated by enormous literary ambition as well as a never-ending string of creditors and endless cups of coffee; as Herbert J. Hunt has written, he engaged in “orgies of work punctuated by orgies of relaxation and pleasure.” When Balzac was working, his writing schedule was brutal: He ate a light dinner at 6:00 P.M., then went to bed. At 1:00 A.M. he rose and sat down at his writing table for a seven-hour stretch of work. At 8:00 A.M. he allowed himself a ninety-minute nap; then, from 9:30 to 4:00, he resumed work, drinking cup after cup of black

...more

When Napoléon III seized control of France in 1851, Hugo was forced into political exile, eventually settling with his family on Guernsey, a British island off the coast of Normandy. In his fifteen years there Hugo would write some of his best work, including three collections of poetry and the novel Les Misérables. Shortly after arriving on Guernsey, Hugo purchased Hauteville House—locals believed it was haunted by the ghost of a woman who had committed suicide—and set about making several improvements to the property. Chief among them was an all-glass “lookout” on the roof that resembled a

...more

He rose at dawn, awakened by the daily gunshot from a nearby fort, and received a pot of freshly brewed coffee and his morning letter from Juliette Drouet, his mistress, whom he had installed on Guernsey just nine doors down from Hauteville House. After reading the passionate words of “Juju” to her “beloved Christ,” Hugo swallowed two raw eggs, enclosed himself in his lookout, and wrote until 11:00 A.M. Then he stepped out onto the rooftop and washed from a tub of water left out overnight, pouring the icy liquid over himself and rubbing his body with a horsehair glove. Townspeople passing by

...more

As the sun set Hugo spent either a boisterous evening at Juliette’s, joined by friends for dinner, conversation, and cards, or a rather gloomy one at home.

Erdos owed his phenomenal stamina to amphetamines—he took ten to twenty milligrams of Benzedrine or Ritalin daily. Worried about his drug use, a friend once bet Erdoos that he wouldn’t be able to give up amphetamines for a month. Erdos took the bet and succeeded in going cold turkey for thirty days. When he came to collect his money, he told his friend, “You’ve showed me I’m not an addict. But I didn’t get any work done. I’d get up in the morning and stare at a blank piece of paper. I’d have no ideas, just like an ordinary person. You’ve set mathematics back a month.” After the bet, Erdos

...more

In his memoir On Writing, King compares fiction writing to “creative sleep,” and his writing routine to getting ready for bed each night: Like your bedroom, your writing room should be private, a place where you go to dream. Your schedule—in at about the same time every day, out when your thousand words are on paper or disk—exists in order to habituate yourself, to make yourself ready to dream just as you make yourself ready to sleep by going to bed at roughly the same time each night and following the same ritual as you go. In both writing and sleeping, we learn to be physically still at the

...more