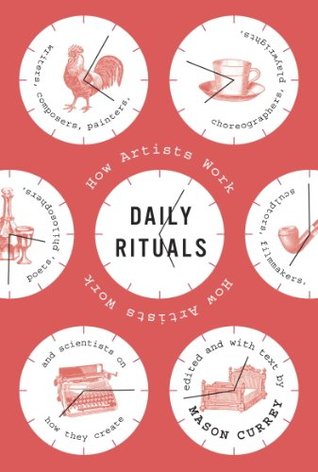

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“Tell me what you eat, and I shall tell you what you are,” the French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin once wrote. I say, tell me what time you eat, and whether you take a nap afterward.

Alan John Varghese and 1 other person liked this

“Sooner or later,” Pritchett writes, “the great men turn out to be all alike. They never stop working. They never lose a minute. It is very depressing.”

to the minute and with accompanying routines.” Auden believed that a life of such military precision was essential to his creativity, a way of taming the muse to his own schedule. “A modern stoic,” he observed, “knows that the surest way to discipline passion is to discipline time: decide what you want or ought to do during the day, then always do it at exactly the same moment every day, and passion will give you no trouble.”

There were no parties, no receptions, no bourgeois values. We completely avoided all that. There was the presence only of essentials. It was an uncluttered kind of life, a simplicity deliberately constructed so that she could do her work.

Fortunately, Highsmith was rarely short of inspiration; she had ideas, she said, like rats have orgasms.

“Do you know what moviemaking is?” Bergman asked in a 1964 interview. “Eight hours of hard work each day to get three minutes of film. And during those eight hours there are maybe only ten or twelve minutes, if you’re lucky, of real creation. And maybe they don’t come. Then you have to gear yourself for another eight hours and pray you’re going to get your good ten minutes this time.”

“I have been working all the time,” he said, “and it’s like a flood going through the landscape of your soul. It’s good because it takes away a lot. It’s cleansing. If I hadn’t been at work all the time, I would have been a lunatic.”

When he did find the time to compose, Feldman employed a strategy that John Cage taught him—it was “the most important advice anybody ever gave me,” Feldman told a lecture audience in 1984. “He said that it’s a very good idea that after you write a little bit, stop and then copy it. Because while you’re copying it, you’re thinking about it, and it’s giving you other ideas. And that’s the way I work. And it’s marvelous, just wonderful, the relationship between working and copying.” External conditions—having the right pen, a good chair—were important, too. Feldman wrote in a 1965 essay, “My

...more

“Altogether I have so much to do that often I do not know whether I am on my head or my heels,” Mozart wrote to his father.

All those I think who have lived as literary men,—working daily as literary labourers,—will agree with me that three hours a day will produce as much as a man ought to write. But then, he should so have trained himself that he shall be able to work continuously during those three hours,—so have tutored his mind that it shall not be necessary for him to sit nibbling his pen, and gazing at the wall before him, till he shall have found the words with which he wants to express his ideas.

Sometimes I don’t understand why my arms don’t drop from my body with fatigue, why my brain doesn’t melt away. I am leading an austere life, stripped of all external pleasure, and am sustained only by a kind of permanent frenzy, which sometimes makes me weep tears of impotence but never abates. I love my work with a love that is frantic and perverted, as an ascetic loves the hair shirt that scratches his belly. Sometimes, when I am empty, when words don’t come, when I find I haven’t written a single sentence after scribbling whole pages, I collapse on my couch and lie there dazed, bogged down

...more

(And although he had many patients who relied on him, Jung was not shy about taking time off; “I’ve realized that somebody who’s tired and needs a rest, and goes on working all the same is a fool,” he said.)

“Mediterranean yoga,” a nap, but for just five minutes;

When the writing wasn’t going well, he would often knock off the fiction and answer letters, which gave him a welcome break from “the awful responsibility of writing”—or, as he sometimes called it, “the responsibility of awful writing.”

“It has become increasingly plain to me that the very excellent organization of a long book or the finest perceptions and judgment in time of revision do not go well with liquor,” he wrote.

“I wish I had a routine for writing,” Miller told an interviewer in 1999. “I get up in the morning and I go out to my studio and I write. And then I tear it up! That’s the routine, really. Then, occasionally, something sticks. And then I follow that. The only image I can think of is a man walking around with an iron rod in his hand during a lightning storm.”

“I keep to this routine every day without variation,” he told The Paris Review in 2004. “The repetition itself becomes the important thing; it’s a form of mesmerism. I mesmerize myself to reach a deeper state of mind.”

But the important thing is that I don’t do anything else. I avoid the social life normally associated with publishing. I don’t go to the cocktail parties, I don’t give or go to dinner parties. I need that time in the evening because I can do a tremendous amount of work then. And I can concentrate. When I sit down to write I never brood. I have so many other things to do, with my children and teaching, that I can’t afford it. I brood, thinking of ideas, in the automobile when I’m driving to work or in the subway or when I’m mowing the lawn. By the time I get to the paper something’s there—I can

...more

For the morning writing, her ritual is to rise around 5:00, make coffee, and “watch the light come.” This last part is crucial. “Writers all devise ways to approach that place where they expect to make the contact, where they become the conduit, or where they engage in this mysterious process,” Morrison said. “For me, light is the signal in the transaction. It’s not being in the light, it’s being there before it arrives. It enables me, in some sense.”