More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“Tell me what you eat, and I shall tell you what you are,” the French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin once wrote. I say, tell me what time you eat, and whether you take a nap afterward.

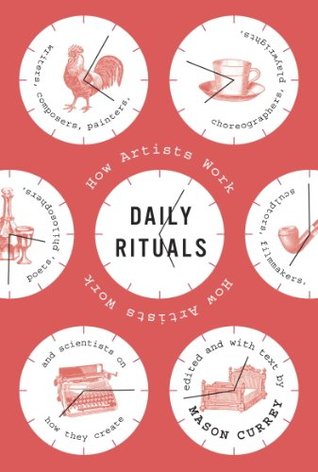

The book’s title is Daily Rituals, but my focus in writing it was really people’s routines. The word connotes ordinariness and even a lack of thought; to follow a routine is to be on autopilot. But one’s daily routine is also a choice, or a whole series of choices. In the right hands, it can be a finely calibrated mechanism for taking advantage of a range of limited resources: time (the most limited resource of all) as well as willpower, self-discipline, optimism.

A solid routine fosters a well-worn groove for one’s mental energies and helps stave off the tyranny of moods.

To maintain his energy and concentration, the poet relied on amphetamines, taking a dose of Benzedrine each morning the way many people take a daily multivitamin.

she had an unusually intense connection with animals—particularly cats, but also snails, which she bred at home. Highsmith was inspired to keep the gastropods as pets when she saw a pair at a fish market locked in a strange embrace. (She later told a radio interviewer that “they give me a sort of tranquility.”) She eventually housed three hundred snails in her garden in Suffolk, England, and once arrived at a London cocktail party carrying a gigantic handbag that contained a head of lettuce and a hundred snails—her companions for the evening, she said. When she later moved to France, Highsmith

...more

Beethoven rose at dawn and wasted little time getting down to work. His breakfast was coffee, which he prepared himself with great care—he determined that there should be sixty beans per cup, and he often counted them out one by one for a precise dose.

And yet, as difficult as the writing was, it was in many ways an ideal life for Flaubert. “After all,” as he wrote years later, “work is still the best way of escaping from life!”

“Functioning as a composer was his whole world,” Donald Mitchell recalled. “The creativity had to come first.… Everyone, including himself, had to be sacrificed to the creative act.”

“There are no rules,” he says. “One has to be open to the reality—and it’s a very wonderful reality—that the next piece is going to hold some surprises for you.”

This routine was as follows: Kant rose at 5:00 A.M., after being woken by his longtime servant, a retired soldier under explicit orders not to let the master oversleep.

Course—James argued that the “great thing” in education is to “make our nervous system our ally instead of our enemy.”

There is no more miserable human being than one in whom nothing is habitual but indecision, and for whom the lighting of every cigar, the drinking of every cup, the time of rising and going to bed every day, and the beginning of every bit of work, are subjects of express volitional deliberation.

“I shall always be depressed,” Beckett concluded, “but what comforts me is the realization that I can now accept this dark side as the commanding side of my personality. In accepting it, I will make it work for me.”

He feared his own volatility and often referred to his need for habitual routines to keep him sane. The job gave him day-to-day stability as well as experiences that he could use in his writing. It was also much less demanding than fiction. He

In her autobiography, Christie admitted that even after she had written ten books, she didn’t really consider herself a “bona fide author.” When filling out forms that asked for her occupation, it never occurred to her to put down anything other than “married woman.” “The

Still, as much as he had hated working, Cornell found that he hated not working too.

“With a stiff prick I can read the small print in prayer books but with a limp prick I can barely read newspaper headlines.”

During the afternoon he would often take an additional nap, lying down on a thinly padded wooden bench or even a concrete ledge; the uncomfortable perch, he said, prevented him from oversleeping.

Years earlier, a writing instructor had advised O’Connor to set aside a certain number of hours each day to write, and she had taken his advice to heart; back in Georgia she came to believe, as she wrote to a friend, that “routine is a condition of survival.”

Coal mining is hard work. This is a nightmare.… There’s a tremendous uncertainty that’s built into the profession, a sustained level of doubt that supports you in some way. A good doctor isn’t in a battle with his work; a good writer is locked in a battle with his work. In most professions there’s a beginning, a middle, and an end. With writing, it’s always beginning again. Temperamentally, we need that newness. There is a lot of repetition in the work. In fact, one skill that every writer needs is the ability to sit still in this deeply uneventful business.

Inspiration can pass through the soul just as easily in the midst of an orgy as in the silence of the woods, but when it is a question of giving form to your thoughts, whether you are secluded in your study or performing on the planks of a stage, you must be in total possession of yourself.

He stayed there until 2:00, taking a brief break for lunch with his family, during which he often seemed to be in a trance, eating mechanically and barely speaking a word before hurrying back to his desk.

According to Mabel’s journal, Bell explained to her that “I have my periods of restlessness when my brain is crowded with ideas tingling to my fingertips when I am excited and cannot stop for anybody.” Mabel eventually accepted his relentless focus on his work, but not without some resentment. She wrote to him in 1888, “I wonder do you think of me in the midst of that work of yours of which I am so proud and yet so jealous, for I know it has stolen from me part of my husband’s heart, for where his thoughts and interests lie, there must his heart be.”

The painting is like a thread that runs through all the reasons for all the other things that make one’s life.

“When I think of death,” she once said, “I only regret that I will not be able to see this beautiful country anymore.”

I intuitively understood that smoking doubled my faculty of concentration, allowing me to be entirely within a canvas.

After trying many schemes, Bucky found a schedule that worked for him: He catnapped for approximately thirty minutes after each six hours of work; sooner if signaled by what he called “broken fixation of interest.” It worked (for him). I can personally

“A mathematician,” he liked to say, “is a machine for turning coffee into theorems.”

“Between books I take vacations that tend to linger on for months. Indolence-and-melancholy then becomes my major vice, until I get back to work. A writer must be hard to live with: when not working he is miserable, and when he is working he is obsessed. Or so it is with me.”

The only reason I write is because it interests me more than any other activity I’ve ever found.

a four-hour sleep in the afternoon enabled him to remain mentally and physically active until the early dawn, when he would again go to sleep for four hours and wake ready for the day.”

When she has a new idea for a performance, it takes over her life. But when she is not giving a performance or preparing for one, she is a different creature entirely. “In my personal life, if I don’t have a project, I don’t have any discipline,” she says. Neither does she follow a regular daily routine.

I walk outside my Manhattan home, hail a taxi, and tell the driver to take me to the Pumping Iron gym at 91st Street and First Avenue, where I work out for two hours. The ritual is not the stretching and weight training I put my body through each morning at the gym; the ritual is the cab. The moment I tell the driver where to go I have completed the ritual.

King writes every day of the year, including his birthday and holidays, and he almost never lets himself quit before he reaches his daily quota of two thousand words.

I have benevolent insomnia,” she said. “I wake up, and my mind is preternaturally clear. The world is quiet. I can read or write. It seems like stolen time. It seems like I have a twenty-eight-hour day.”

“It will appear like a calm existence,” Kalman said. “The turmoil is invisible.”

The Belgian-French novelist worked in intense bursts of literary activity, each lasting two or three weeks, separated by weeks or months of no writing at all.