More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

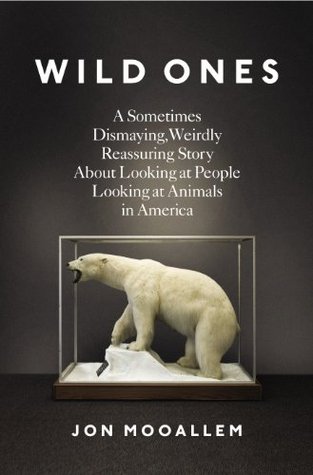

Jon Mooallem

Read between

August 27 - September 5, 2017

No one imagined it would come to this. And no one can say how far it will go. In a recent scientific paper, a group led by the government biologist J. Michael Scott conceded that a fundamental belief behind so much conservation—that we can “save” a species by solving a particular problem it faces, then walk away and watch it thrive—is largely a delusion. “Right now,” Scott says, “nature is unable to stand on its own.” We’ve entered what some scientists are calling the Anthropocene—a new geologic epoch in which human activity, more than any other force, steers change on the planet. Just as

...more

I’d started reading historical accounts of wildlife in America—a little obsessively. Part of what I was hoping to do for Isla by showing her endangered animals in the wild was offset the environmental generational amnesia that would inevitably take hold between her and me—to help her know a world, a baseline, that preceded her. But I was also learning about the world that preceded me. And what always leapt out of those accounts was the simple fact of abundance: people’s descriptions of being dwarfed and engulfed by wild animals, or even just massively inconvenienced by them. Americans are

...more

There is an assumption, writes the environmental legal scholar Holly Doremus, that “what nature needs most is for people to leave it alone”—that a landscape will “automatically produce the preferred human outcome, a perfect Garden of Eden, if it is simply walled off from human influence.” But nature doesn’t know what outcome we want, and it doesn’t care. Instead, it perpetually absorbs what we do or don’t do to it, and disinterestedly spits out the effects of those causes. Nature is not a photograph that will always look good if we keep our fingerprints off it. It’s a calculator, adding up

...more

In an environmental law review article on the subject, the scholar Holly Doremus criticizes this sort of restrictive wildlife management as “erect[ing] a virtual cage” around animals. Conservation should strive to build healthy populations of animals that are “as wild as possible in a tame world.” But controlling and manipulating animals, or making apologies and payouts for them, effectively amounts to a kind of domestication, changing species “from wild animals to human creations designed to serve human needs.” Just as a cow on a fenced-in pasture meets America’s need for beef, a buffalo

...more

“The underlying message is, otters don’t stay where we put them.”

“You can’t take humanity out of the equation,” Brooke told me. “Humanity caused the problem to begin with, and so it’s very hard for humanity to solve the problem. Because it’s humanity! You know what I mean? We bring to the table all the same crap that was brought to the table to create the nightmare in the first place!”

The Owens pupfish lives in the pools at Fish Slough and nowhere else in the world. It’s two inches long and otherwise so mundane-looking that it escaped my powers of description, no matter how intently I stared at the photo of one on Pister’s wall and tried to jot down something meaningful about it in my notebook. It is beige.