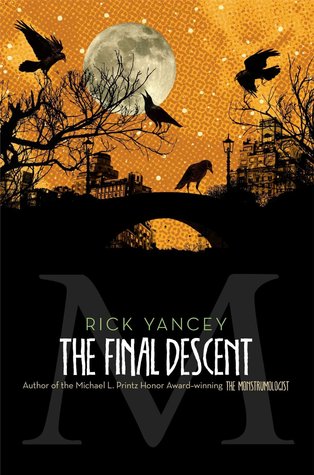

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“Its venom is the most toxic on record, five times as potent as that of Hydrophis belcheri. A drop that would fit upon the head of a pin is enough to kill a grown man.” I whistled. “No wonder it is so valuable. You could wipe out an entire army with a cupful. . . .” He shook his head and chuckled ruefully. “And thus our own natures determine our conclusions.” “What do you mean?” “It is valuable not for what it takes away, Will Henry. It is valuable for what it gives.” “That was my point, Doctor.” “Death as something one gives?” “And receives. It is both.” Still smiling: “I really have failed,

...more

I set the gun beside the nest and contemplated the gestating T. cerrejonensis. It glowed in the orange light of the heat lamp. The basement was cold; the place in which it rested was warm. Three days before, it had begun to quiver, ever so slightly, nearly unperceptively. When you listened through the stethoscope, you could hear it, a wet squishy sound, as the organism writhed and twisted within the amniotic sac. Hearing it gave you a certain thrill: This was life, fragile and elemental, tender and implacable. Entropy and chaos reigns o’er all of creation, destruction defines the universe, but

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Scratch, scratch. The thing behind the thick glass. The thing in the burlap sap. Scratch, scratch. Form casts shadow and all shadows are the same: There is no difference between the thing behind the glass and the thing in the sack. Their essence—to ti esti—is the same. All life is beautiful; all is monstrous.

The monstrumologist gave in to Lilly’s suggestion, accepting her offer—and her arm—to help him up the stairs. “You have failed me,” he said to me. “Once again.” I might have pointed out that my “failure” had resulted in the continuation of his disagreeable existence, but I held my tongue—as I so often did. Such retorts only led to an escalation of counter-retorts and counter-counter-retorts ad nauseam, and lately it had struck me how embarrassingly like an old married couple we had become in our discourse. It also occurred to me that the continuation of his disagreeable existence might be the

...more

And the carapace split apart, a thick yellowish liquid oozed from the crack, then the ruby red mouth and the round black head the size of my knuckle emerged, and then teeth the colorless white of bleached-out bone: life inexorable and self-defeating, ends contained in beginnings, and the pungent odor like fresh-tilled earth and the amber eye unblinking. Beside me the monstrumologist let out a long-held breath. “Behold: the awful grace of God, from which wisdom comes!”

“The man is as useless as . . .” Warthrop searched for the proper metaphor. Pelt drawled a suggestion: “Teats on a bull.” “Gentlemen, gentlemen,” von Helrung admonished gently. “We have not gathered here to discuss Dr. Walker’s teats.”

“You are leaving out the worst possibility of all,” Warthrop said. “That someone may kill it.”

“Warthrop’s attack dog.” He sneered down at me. “His personal assassin. I’ve heard about you and Aden—the Russians at the Tour du Silence—and the Englishman in the mountains of Socotra. How many others have you murdered at his behest?” “About one short,” I gasped. “But it wouldn’t be at his behest.” It is exceedingly difficult to laugh heartily without opening your mouth, but somehow Isaacson managed it. “I hope you like the Beastie Bin, Henry. You’ll be an exhibit there one day.”

I don’t know why, perhaps it was her laughter, the pleasing jingle of coins tossed upon a silver tray, but I kissed her, still heaving for air, a pleasant suffocation. “I’m a bit troubled, Mr. Henry,” she breathed in my ear, “by this curious association you have of violence with affection.” I was grateful, in a way, that I had no breath with which to answer.

“She has a certain . . . fascination for such things.” “And you? Where do your fascinations lie?” I knew what he meant. “I thought we had exhausted this topic at the dance.” “At which point you proceeded to break her dance partner’s jaw.” For some reason he found my remark amusing. “Anyway, the topic, as I understand it, is nearly inexhaustible.” “You exhausted it,” I reminded him. “After it drove me into the Danube.” I might have told him it wasn’t love that hurled him over that bridge in Vienna—or at least not love for another person. Despair is a wholly selfish response to fortune’s slings

...more

“And I didn’t lose much blood, thanks to the ministrations of your paramour.” “She isn’t my paramour.” “Well, whatever she is.” “She annoys the hell out of me.” “So you’ve said more than once. And what is this with the expletives lately? Cursing is the crutch of an unimaginative mind.” “I like that,” I said. “One day I intend to gather all your pithy sayings into a volume for mass consumption: The Wit and Wisdom of Dr. Pellinore Warthrop, Scientist, Poet, Philosopher.” His eyes lit up. He thought I was serious. Perhaps he’d already forgotten my shitty remark in the taxi. “Wouldn’t that be

...more

“It is my fault,” I whispered to the bones beneath my feet. “I should have known when I left him that he would fall off the edge of the goddamned world.”

Daylight dwindled, but I remained on the stoop. I resisted the instinct to rush inside and confront him. He was a stranger to me, the man who had been my sole companion for nearly twenty years, the man whose moods I had been able to read like an ancient mystic decoding the bloody entrails of the sacrificial lamb. I honestly did not know how he would react. I drew my coat tightly across my chest. Ashes swirled in the gray air. A thought flittered across the broken landscape: It would be better if he were dead. A mewling cry rose from deep in my throat, and I remembered the lambs, dark-eyed,

...more

And then, perhaps because she heard my voice, the elegant woman swept into the vestibule, the woman whose angelic voice had sung me back to sleep with words I did not understand, the same who had said, the last we met, It is no accident of circumstance that you’ve come to me—it is the will of God.

She would fly down the hall chasing the startled, nightmare cries of her accidental charge and gather him into her arms, stroking his hair and pressing her lips to his head, and her voice when she sang to him was unlike anything he had ever heard, and sometimes in his confusion and grief he would forget and call her Mother. She never corrected him.

Had I eaten? Did I want something to drink? And the woman sitting on the edge of her chair with knees demurely pressed together leaning forward and the bright von Helrung eyes shining beacons even here in the gathering shadows. She had held me and sung to me, and now I felt nothing, nothing at all, and was angry with myself for it.

I cleared my throat. “I have never told you this . . .” She laughed. “I’m sure there are many things . . .” “. . . but there were times your letters were the only . . .” “. . . you have never told me.” “. . . solace I had.” She took a deep breath. “Solace?” “Comfort.” “Your life is uncomfortable?” “Unusual.” “Then receiving a simple letter must be an extraordinary thing.” “It is. Yes.” “Are you now? Uncomfortable?” “Yes, I am a little.”

“I don’t wish to be your brother.” “Then what do you wish to be?” “Of yours?” “Of anything’s.” “I don’t want to be anything’s—” “Then why don’t you leave him? Does he chain you up at night?” “I intend to leave him, when the time is right. I have no interest in becoming what he is.” “And what is he?” “Not anything I want to be.” “That’s my question, Will. What is it that you wish to be?” I rubbed my hands together, staring at the floor. And her eyes, bird bright, upon my face. “You told me once that you were indispensable to him,” she said softly. “Do you think you may have that backward?” I

...more

“You aren’t going to kiss me again, are you?” she asked, lips slightly parted. “I should,” I murmured in reply, edging closer to the lips slightly parted. “Then why don’t you? Not enough wine or not enough blood?”

“There is something I must tell you,” I whispered, my lips a hair’s breadth from hers, close enough to feel the heat of them and to smell her warm, sweet breath. “Does it have to do with free love?” she asked. “In a very roundabout way,” I answered, the words sticking in my throat. I could see my parents dancing in the blue fire of her eyes. “There is something inside of me . . .” “Yes?” I could not go on. My thoughts would not hold still. It burns, it burns, and the worms that fell from his eyes and afraid of needles are you and what would you do, and Lilly, Lilly, do not suffer me to live

...more

And I replied, “I don’t know what that means. If you define madness as the opposite of sane, you are forced into providing a definition of sanity. Can you define it? Can you tell me what it is to be sane? Is it to hold no beliefs that are contrary to reality? That our thoughts and actions contain no absurd contractions? For example, the hypocrisy of believing that killing is the ultimate sin while we slaughter each other by the thousands? To believe in a just and loving God while suffering that is imaginable only to God goes on and on and on? If that is your criterion, then we are all

...more

“He’ll find you out, both of you, and what do you think will happen to you when he does? You’ve said it yourself: ‘Warthrop’s attack dog.’ You know what happened in Aden. You know about the Isle of Blood.”

And in me the thing unwinding.

Isaacson was waiting impatiently for me at the back of the dray; for him the night had been too long already. At least it will end for you, I thought bitterly.

He stopped and turned slowly around to face me. “Where is our driver?” he demanded, his voice rising in distress. “Behind you,” I answered. He did not have the opportunity to turn round again. The unwinding thing sprang free, uncoiling with enough force to break the world in half.

In the basement laboratory, when the chrysalis cracked open, I saw myself reflected in the amber eye. I was the humble conduit to the monster’s birth, the imperfect midwife, deliverer and prey. Forgive, forgive, for you are greater than I.

“Oh, what do you know about anything?” “I know about the lambs,” I said. “And I know what you cut up and stuffed into an ash barrel. I know they both have something to do with the lock upon that door and your deplorable condition—and I know you will show it to me, because you cannot help yourself, because you know with whom your salvation lies. You have always known.” He fell forward, burying his head in his folded arms, and the monstrumologist cried. His shoulders shook with the force of his tears. I watched impassively. “Warthrop, give me the key or I shall break it down.” He raised his

...more

In Egypt, they called him Mihos, the guardian of the horizon. It is a very thin line, Will Henry, he told me when I was a boy. For most, it is like that line where the sea meets the sky. It cannot be crossed; though you chase it for a thousand years, it will forever stay beyond your grasp. Do you realize it took our species more than ten millennia to realize that simple fact? That we live on a ball and not on a plate?

“Have you ever been in love, Mr. Faulk?” “Oh, yes. Many times. Well, once or twice.” “How did you know?” “Mr. Henry?” “I mean, did you know in the same way you know that red is red and not, for example, blue?” He looked off into the distance, lost in memory or pausing to give my question its proper due. “Been my experience you don’t know till after the fact.” “After the . . . ?” “When it’s gone.” “I don’t think I love her.” “If you don’t think it, then you don’t.” “But I would have killed him if she had—or they had—he had . . .” “I’d say that’s more blue than red, Mr. Henry.” “Do you think it

...more

The men noticed her almost at once, but the women sooner; that is the way with beauty.

The boy did not hurry through the throng; I easily kept up with the little hat bobbing along, the hat that reminded me of another hat, two sizes too small, which belonged to another boy in another age.

His eyes are my eyes, the boy crouching under the table in the hat two sizes too small: wide, uncomprehending, beseeching, terrified. This is the end of the long dark tunnel, and I must not suffer him to face the faceless singularity; I am the breakwater to spare him the surge of the dark tide. It doesn’t have to be, the thing scratching in the jar and the man in the stained white coat saying You must become accustomed to such things. I can save the boy beneath the table; I can save him from the amber eye; it is within my power. Raising the gun to the level of his eyes. Do you know who I am?

“Why would anyone share that with you?” “Because I am . . .” I stuttered to a stop, face burning, hands clenched at my sides. “Yes. Tell me,” he said softly. “What are you?” I wet my lips. My mouth was bone-dry. What was I? “Misinformed,” I said finally.

I bore a special responsibility, not because I felt in any way responsible for von Helrung’s death—no, fate had decreed me his sole caretaker, the lone guardian of the Warthropian animus. It had taken me years to understand this. He didn’t need me to sustain his body. He could hire a cook to feed him, a tailor to clothe him, a washerwoman to keep those clothes clean, a valet to wait upon him hand and foot. What he could not afford, though he possessed the wealth of Midas, the one indispensable service that only I could provide, was the care and feeding of his soul, the nurture of his towering

...more

What are you? he had asked. It was a disingenuous question. He knew very well what I was, what I had always been without either of us understanding it, much less acknowledging it. And what did it matter if we did? Would it have changed anything?

I woke with a start, for a moment ignorant of my location, thinking I was back at Harrington Lane and the doctor was in the next room reading, dinner was through, the plates washed and stacked, and this was the best part of the evening, when Warthrop gave me some peace and I felt a little less burdened, the weight upon my shoulders a little less heavy.

“Uncle never had children. So to him practically everyone is. He has a very soft heart for a doctor of monstrumology.” “The last of his kind.” “What does that mean?” “Nothing. Only . . . only it always surprised me, your uncle’s kindness, his . . . gentleness. What he was didn’t fit what he did.”

“The monster is dead; the monster never dies. You may catch it; you will never catch it. Hunt it for a thousand years and it will forever exceed your grasp. Kill it, dissect it, place its parts in a jar or scatter them to the four corners of the world, but it remains forever one ten-thousandth of an inch outside your range of vision. It is the same monster; only its face changes. I might have killed him, but it doesn’t matter one way or the other. The next one I will, and the next, and the one after that, and the faces will change but not the monster, not the monster.”

“If he had said yes on that bridge, I wouldn’t have dropped him.” “Really?” She laughed. “I would have.”

“I had the oddest dream,” he said. “I found myself descending a narrow stair. There was no rail and the steps were slick, covered in slime. I could not see the bottom and did not know my destination, though it was imperative that I reach the bottom. Time was of the essence, but I was forced to proceed slowly lest I slip and tumble all the way down. I realized where I was: Harrington Lane, and these were the steps leading down to the basement. At the thirteenth step, the stairs turned, so I could not tell how far I had left to go. Down, down, I went, until there was no light, I was descending

...more

“Stop saying that. What has happened to you? What are you, William James Henry? Where are you? I seek you, but I cannot find you. The boy I knew would never have—” “The boy you knew—where is he? He is in Aden, Dr. Warthrop. And Socotra. And on Elizabeth Street.”

“You’re wrong!” I shouted. “There is no difference! In me or what I did or what I will do. I am the same; nothing has changed. You are the heartless one. You are the monstrous one. I never asked to be this. I had no choice or say in it!” He grew very still. “You never asked to be what?” “What you have made me.”

“It is the truth,” I said calmly. “The thing you claim to love above all else. You asked what I am, but you know already: I am the thing that waits for you at the bottom of those stairs.”

I threw open the door. He shouted for me to close it, and I, ever the faithful servant, started to—then stopped. “I said close that door.” “I am leaving you, Dr. Warthrop,” I said, facing the open door and the hall outside and the elevator that would take me down a final descent and out the lobby and into a world without monstrumology and murder and the things that claw helplessly in glass jars and the inarticulate horrifying beauty that dwells in the chrysalis. I was light-headed, extremities tingling, heart buzzing with adrenaline. Freedom. He barked out a laugh. “And where will you go? And

...more

How absurdly simple, I thought, and how simply absurd—the chain that bound me was made of air! The prison that housed me had walls insubstantial as water; I only needed to kick hard to break the surface and be free. Free! I was hurtling along at a hundred times the speed of light, flying to the ticket office first, unbound and unhindered, the past receding to a point infinitesimally small behind me. Free! I heard their cries from the flames no longer, nor his voice, desperate and shrill, calling me, Will Henreeeeee! and to hell with those who dance in flames and to things that swim in jars and

...more

“I am, but not with drink. I don’t know why I never saw it before—but you did, from the beginning you saw. My doctor, you called him. I wasn’t his; he was mine. And what belongs to me I may keep or discard as I wish. As I wish!”

“I love you, Lilly.” She turned her head away. “No.” “I do. I love you. I have loved you since I was twelve years old. And I would do anything for you. Name it. Name it and it’s yours.” She looked at me. And her eyes were blue and clear all the way down, like the lake high in the Socotran mountains into which I had plunged to wash away my contagion. I was nasu, unclean, and the icy water purified me. Yes! I thought. And herein lies our salvation.

“Please, Lilly, don’t turn me away. I could not bear it. I never told you this and I should have told you this and I don’t know why I never told you this, but your letters were the only things that kept me going. Your letters tied me down, kept me from flying away into nothing. Please, Lilly, please let me come with you. Let me prove to you that you’re not an excuse but the reason. There is nothing missing. I am whole. I am human.” “Human?” She looked startled. “He told me once that I was the one thing that kept him human, and I didn’t understand what he meant, but now I think I do: I bound

...more

And the dark thing inside sprang free . . . uncoiled with enough force to break the world in half . . . and Lilly before me, lips slightly parted, and me pressing my hands hard against her cheeks, her skull as delicate as a bird’s, and in me the darkness, the abyss, the nullity, the crushing singularity, the unalloyed madness of my perfect sanity, and he had said it, the one who had ripped off the human face to expose the tragic farce beneath, for which he had earned the deliciously ironic sobriquet Ripper, he had said it: Your eyes have come open. You see in the dark places where others are

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

We stood for a moment, smiling at each other. “That girl,” he said. “You should take her with you.” “You are a hopeless romantic, Mr. Faulk.” “Oh, what’s it all worth without that, Mr. Henry?”