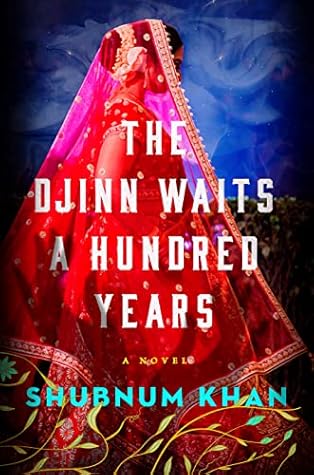

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

The west coast, he says, has many good things, like mussels and otters and small, wild roads, but it is cold and windy and there are too many white people. You can’t trust a place with too many white people, he says.

“Ha! Please. That thing is not sensitive. Did you hear him? Arreh bapre, he called God’s name in vain. How he can say like that? Even a deaf thing like you must have heard. It’s . . . outrageous, outrageous I tell you,” she says, clinging to the dramatic English word she has unexpectedly discovered in her vocabulary. “I won’t have God’s name taken in vain by a Hindu bird in a decent Muslim house like this.”

To see two human beings merge seamlessly into one distinct shape left her breathless. From then on, she has tried to discover how love affects the shape of things.

Conjoined twins were for white people in soap operas and medical dramas. It wasn’t for people in the real world who had real lives with real problems.

Sana watches as Doctor changes shape in front of her as he speaks. The dawn breaks and he is no longer a lonely man with frail hands; he is a strong, young man with wild hair and bright eyes, and she realizes then a memory can make you whole.

But the girl has something the others do not: a questionable amount of soul. And a questionable amount of soul is a dangerous thing. It makes people unpredictable; it can send them out in the darkness to seek things that others would never dare. It can keep a flame burning, long after it was supposed to go out.

He brings an architect from India, a descendent of the great Ustad Ahmad Lahori; he asks for glass domes, guldastas, brass finials, ornately cut passages, Spanish balconies, stilted arches, stone towers, Palladian windows, and marbled floors. He orders lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, has cedarwood brought in from the Atlas Mountains and Carrara marble from Italy. He has Lebanese stained-glass windows imported from Sidon. Arabic calligraphy is etched into cornices and ivory arabesque worked into column capitals. Moroccan craftsmen build Zellij mosaic floors and walls in the courtyard.

“From the day a girl is born she’s told she needs a love story to survive. It’s everywhere: in poetry, in music, in films and books. She’s told life is worthless without love. She’s told she is worthless without love.” She lowers her voice. “But what no one tells her, what no one talks about, is that it can kill her. That the very thing they say can save her can destroy her. Love is a trap, darling. It lures you in then digs its bony fingers into your chest, breaks open your ribs, and yanks out your bloody, beating heart, and still leaves you alive.”

“Love is the worst thing of all because it is a great lie. It promises you everything but gives you nothing. Love leaves, it always leaves.”

The fact that he could make her memories his own made Sana believe that love was not a thing that always left. Love, to her, was the thing that stayed.

When the baby is born and it turns out to be a girl, Grand Ammi does not mince words. She tells her daughter-in-law she is disappointed; it would have been more suitable to have the heir first, but the damage is done and they can do nothing but wait for the next one. She advises her daughter-in-law to eat more fish and drink less milk in order to produce a male.

Her family still lived in poverty, they were punished for their skin color, and they were still answerable to the white man for everything they did. It was still slavery, just in different packaging.

Uṅkaḷ vakai appaṭi illai.

And just like that, quietly and reluctantly, Meena Begum finds herself falling in love with her husband.

Meena Begum props herself up on her shoulder and turns to him. “Tell me, have you forgot yourself?” she asks. “Entirely,” he says. “Why?” “Because we were made for each other before we even met. Our souls found each other on the plains of heaven. I knew it when I saw you.”

“Tell me everything,” she says. “Tell me everything you have ever known,” understanding then what it is like to be in love, to want to know another person as much as yourself, to know their secrets and desires, their histories and hurts. She wants to envelop him, swallow him entirely until she and him are one.

They are two lonely boats floating in a pitch-black sea and when they find each other they hold on.

He, too, talks, bursting with words as if he himself does not know that he has been waiting for a companion to share them with.

They name him Hassan Ali Khan. He is the living manifestation of Akbar and Meena Begum’s love for each other. Together they go through his tiny fingers and toes and admire his catlike eyes that open and close slowly as he blinks at his new world. They look for signs of him and of her and inhale in surprise when his face changes into hers and then suddenly into his like a revolving door that can’t decide where to stop.

7 December 1930 Akbar told me that there are 99 names of God. His favorite is Ya Fatah—the Opener. The Opener of all ways and all things. The one who opened our paths to each other.

“This world is full of flowers, my child, but they’re all just made of paper.”

When they settle down, she says, “I’ll wait for you, Akbar. As I always have, even when I did not know it. I’ll come here every evening with a light and call your name until you find your way back to me.”

Akbar reads Ayatul Kursi under his breath and blows the blessed prayer of protection over his family on land and at sea.

How much brighter the stars shine in the sky when you know you are loved,”

Ya Fathah. The One who opens solutions and removes obstacles. There are 99 names of God. He is the Merciful, the Compassionate, the Wise but this, this one is my favorite, jaan. For God is the opener of everything. He makes any way possible for anyone who asks. Ya Fathah.

“Did we really meet in the heavens before?” I asked Akbar today. “Of course,” he said. “And that is why we recognized each other on earth.” “How come I didn’t recognize you at first?” I asked. “Because you had closed your heart to the Signs,” he said.

The end always returns to the beginning; the circle always seeks to be whole, and so when the end comes for Meena Begum, she is remembering the river and the way it runs through the village like a person, like a friend with a laughing face and open arms. She can hear the sound of rain and the way it fills the river like a drumbeat as it carries away twenty-one grams of soul.

The paper flowers turn to dust.

She turns to her father. She can see that he is more solid than she ever gave him credit for. He is a man who has loved deeply, loves deeply still, and she can see now that a person can be more whole with broken parts.

“Love comes in all forms, even ones we don’t always recognize,” he says, studying the irregular shape.