More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

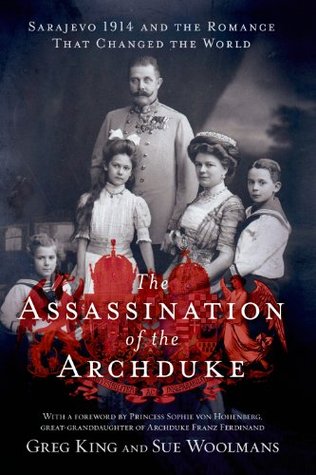

by

Greg King

Read between

March 12 - March 16, 2025

Has any other couple of the last hundred years so inadvertently shaped our modern era?

Royalty and politicians alike fell in precipitous numbers to bombs, bullets, and knives in these “golden” years of peace.

“No other political murder in modern history,” wrote Vladimir Dedijer, “has had such momentous consequences.”6

According to this theory, Russia feared that when Franz Ferdinand came to the throne he would unite the disparate southern Slavs under the Habsburg flag and thus prevent Romanov expansion in the Balkans.

This was the universe of Freud and Mahler, of sexuality and passion, of intellectuals and artists who haunted smoke-filled coffeehouses with their philosophical worries, of anti-Semitism and impoverished workers crowded into disease-ridden tenements.

Klopp was so worried that contrary ideas might influence his pupil that he even literally rewrote the young archduke’s history books himself to remove unwanted and pernicious political notions.

Franz Ferdinand lacked the one thing most prized in Austria: charm.

To most of Vienna, Franz Ferdinand was “grave, strict, and almost gloomy-looking”; gossip held that he was a narrow-minded conservative and religious bigot, someone whose time on the throne would signal ominous things for all of Austria-Hungary.

Everywhere he went, it seemed, Americans were preoccupied with “the Almighty Dollar.” Worse, he was surprised that such a large and prosperous country seemed to have no arrangements for the relief of the poor. “For the working class,” he wrote, “freedom means freedom to starve.”

Franz Ferdinand once insisted, “I would not shrink from breaking off relations even with the Holy Father if he tried to use his powers in the Church against my own views.”

Such sentiments only fed growing perceptions that Serbia was “a thorough-going nuisance, a nest of violent barbarians whose megalomania would sooner or later meet with the punishment it deserved.”