More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

August 5 - August 16, 2024

“I took a phone call, Rachel,” he said firmly. “That's all I did. You're making more out of this than there is, and you know it as well as I do. I can understand that it's upsetting to you, but you are blowing it way out of proportion. Anything I'd say right now isn't going to make a difference. You're going to have to look at our relationship, look at our history, and decide for yourself how much I care about you.”

so simple and natural for other people but so difficult for me. I was like a child finally able to kiss Mommy good-bye without a fuss, content in the knowledge that Mommy still loved her and would be back.

I had dreaded Christmas for precisely this reason, knowing it would literally take days to get over such a dose of family exposure.

I had long since come to recognize myself as a victim. But now I could see them as victims too. They were the legacy of abusive parents who had been the legacy of abusive parents themselves. And on and on and on. Nancy, Sally, Bruce, and Joe—all of them were victims as well. I still hadn't reached a point where I could excuse my family's behavior, but at least I was beginning to find a basis to understand it. It was easy to accept Father Rick's theory of the ripple effects of child abuse.

“Miracles,” he said, “stop the chain. Miracles turn it around. The miracle of love. The miracle of forgiveness. The miracle of a change of heart. No one can force these miracles on anyone else—not even God. It's called free will. We can choose to be open to these miracles, or we can choose to keep our hearts closed and run from them out of fear. It's an individual choice.”

“Someday, Rachel, you'll be able to forgive the person you need to forgive most—yourself. And you will realize what a special person you are.”

But deepest within me I still felt a gnawing emptiness: a warning that I was avoiding something.

In just one more month it would be two years since I had first begun therapy. I was getting better at controlling my emotional reactions. When feelings overwhelmed me, I learned to thwart the burning temptation to act self-destructively and to sit with the feelings instead. By now I had accumulated hundreds and hundreds of yellow legal sheets of paper containing my emotions—written down so I wouldn't take them out on myself or anyone else.

How could I doubt the existence of the subconscious mind when it pushed its way into my life nearly every single night and day?

He suffered. Oh yeah? Well, I've suffered too. I've suffered plenty. And I haven't risen, have I? The sad eyes of the crucifix were staring back at me, as if they were truly watching me. I'd never noticed before just how much sadness lurked in these eyes, the unspeakable pain that went beyond the pain of crucifixion. The gut-wrenching pain of betrayal.

Pain? Why didn't God spare you the cup, spare you the pain of betrayal? What kind of sick Father do you have anyway? You were supposed to be his Only Son—and just look at what he let happen to you! I feel for you, Jesus. I really do. Your Father screwed me over too. Left me hanging, an innocent little kid, to destroy me for the rest of my life. Some Father you have! I can relate.

No wonder I can't trust anyone. If I can't trust God, who in the hell can I trust? The last refuge for the meek, the humble, the poor in spirit, the downtrodden. Does God make life any better? No wonder I don't have faith. It isn't because God doesn't exist or you don't exist; it's because both of you do! And both of you are cruel hypocrites!

“On one level, yes,” he replied. “You're afraid that if you begin to rediscover the pleasure of food, you'll lose all sense of control. You won't be able to enjoy it in moderation. But it isn't just food that makes you feel that way. It's all pleasure, all feeling.”

“Don't you see?” I was exasperated at hearing the same old theories. “This isn't about love—a child's love or anyone else's. This is about clinging. About smothering. About a world centered around myself.” “Which is a perfectly natural state of childhood.”

“This isn't like any other relationship for either of us. As a parent, as a wife, you can't be too self-centered. It would be very destructive. And you aren't too self-centered in those relationships. But it's safe here, safe to feel a child's feelings.”

“You can't skip a phase, Rachel. You can't go to the ego phase without first going through the id. There are no moral implications to it. A child needs to be self-centered long enough to feel secure before she can move on. Whether you go through it when you're three or thirty-three, it doesn't matter. You have to pass through that phase and feel secure enough to move on. And, most important, the phase can and will pass.”

“Needs don't just go away on their own. They have to be satisfied. And if they aren't, they just fester beneath the surface and grow even more shameful and frightening. You have an inordinately strong need for attention because you feel, rightly, that you didn't get as much as you needed when you should have. You buried it in shame, which only served to make the need seem more intense until, finally, you became afraid to need because you figured it would overwhelm anyone you let it touch.

At times I still felt the angst of missing him, a melancholy feeling as I imagined what he might be doing with his family, wishing I could be there to enjoy it with him. But, for the first time, I didn't resent his absence. Surely I preferred that I see him. But I no longer felt as abandoned. I knew he would be coming back, and I knew that the separation didn't sever our feelings.

People could grow; people could change. If anyone knew that, it was me.

I'd come to the realization that nothing was black and white, that I was neither perfectly good nor perfectly evil. The issues of responsibility in relationships were never clear-cut. I wondered how much I contributed to the dysfunction in my family.

I found myself fiercely guarding and limiting my emotional reactions, chastising myself for possible distortions and motivations.

When I related the incident to Dr. Padgett, I was torn between remorse and righteous indignation, between all of my ambivalence about my rediscovered ability to feel and express anger and my fears that I had somehow been irrational or had blown everything wildly out of proportion.

“Welcome to the land of imperfection, Rachel,” he said. “Nobody can completely control their anger all the time. And even if you did overreact a bit, who doesn't sometimes? Everyone is irrational sometimes.” “Even you?” I asked. He smiled broadly then. “Even me.”

“Having human emotions isn't the sin, Rachel; it's what you do with them,” said Father Rick. Thoughts and fantasies never hurt anyone. It's the way someone chooses to act on them.

“Notice that you didn't hear him say ‘forget,’” Father Rick replied. “Jesus never said, ‘Father, forgive them; forget about what they did.’ He didn't say they hadn't done what they'd done to him. He didn't say they hadn't betrayed or hurt him. He forgave, but he didn't forget.

“They know not what they do. He wasn't calling them innocent; he was calling them ignorant. And there's a world of distinction between those two words.”

Maybe, if all people actually did all the things Jesus called them to do, we wouldn't have to wait for heaven. It would be right here on earth.

The priest smiled, “No, your penance is to take care of yourself, to forgive yourself first, and to spend some time every day in prayer thinking about what we've discussed here.”

Despite it all, I did feel love for my parents. And in their own flawed way, they, too, had felt it for me. I could not remain in a distorted world of black and white. Sentencing myself to a powerful anger and desire for revenge would only hold me back.

Forgiveness was not an overnight phenomenon. It happened slowly over time. I was less bitter toward them and more open. Still aware that they had not changed, I did not leave myself vulnerable to the kind of pain they were still capable of inflicting. But, as I let go of the anger, I could also see some of what was good about them, what had been right in my childhood.

They would never be the first people I called in times of emotional crisis. Many parts of my life would remain unknown to them, including the raging anger I had felt at the revelations of what the past had really been. Visiting them, however, was no longer such a painful obligation, and in many ways I came to enjoy their company as adults.

“You have an illness, Rachel,” he said emphatically. “An illness. I wouldn't leave you if you had cancer or diabetes, and I'm certainly not going to leave you because you have an illness of the mind and not the body. If I wanted to be with someone else, I would be. But I don't. I want to be with you. And if I had it to do all over again, knowing all of this, I would still marry you. In sickness and health. We can get through this. We really can.”

I wasn't sure how this chemical combination worked. But I was glad it existed. It reinforced that mental illness, depression, was indeed an illness with a physiological basis. It wasn't a sign of failure. I wasn't a failure.

I vowed that whatever happened in my life after therapy, however full my life might become, I would never forget where I had been and the lessons I had learned. To make sure I could always appreciate the new light of day, I vowed to never forget the pain of the depths of darkness.

“The subconscious mind is always at work,” he explained. “When you terminate, a part of you will feel pride, independence, and joy that you've moved on. But another part of you will still be ambivalent. You could subconsciously create a crisis just to avoid the separation.”

It was goodnight not good-bye, a symbol that even though I would not see him anymore, he would still be standing by my side, comforting me, the blanket of stars the legacy he had left with me.

My termination from therapy had been a graduation of sorts—a sign that I was an adult emotionally as well as chronologically. Now it was time to act like one. I had been pouting, forgetting that I wasn't the only one who could be hurt and confused.

Now able to feel love—to give and receive it—I was no longer abandoned. I had my family. I had my friends. I had my church. I had my God. Now I could reach out and capture those many drops of kindness and love. I would get by. And thrive.

The day before she died I held her frail body close to mine and whispered to her that I loved her, that I'd forgiven her and Dad too. I told her I would look out for Dad for her. Her eyes, which had been transfixed in a semicatatonic state for hours, flashed with life as she smiled and hoarsely whispered back the words “I know.” I cried openly at the funeral, but they were the healthy tears of closure not the bitter ones of remorse.

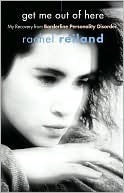

What it is, I hope, is a way for readers to get a true feel for what it's like to be in the grips of mental illness and what it's like to strive for recovery. Most important, the reason I wrote this book is to serve as proof that miracles do happen, that love can and does heal wounds, that there is hope for those with the courage and fortitude to seek healing.