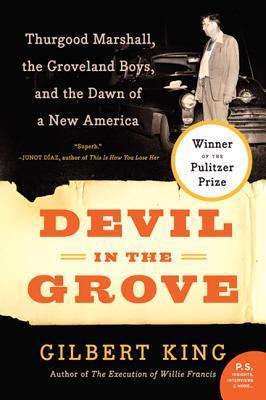

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Gilbert King

Read between

April 30 - May 15, 2018

He noted that the whites he spoke with were less interested in seeking revenge for the rape of Norma Padgett than in seeing the demise of “all independent colored farmers.”

After World War I, dozens of Negro soldiers had been lynched in the South, some of them still wearing their uniforms, and in the summer of 1946 the lynchings of black veterans resumed with a vengeance.

“At one moment he [Hunter] would have the most acerbic and bitter racist comment,” Williams noted, “and then the very next moment he would be the most pleasant good fellow, country lawyer you had ever met.”

“You keep talking about equal justice, equal facilities. We’re setting up an atom smasher at the University of Oklahoma. Do you mean that we’ve got to set up an atom smasher for niggers? Everybody knows that niggers can’t study science.”

“Notice Negro Blood on Your Grapefruit?”

Peaches and Evangeline gazed helplessly down at the wilted flowers atop the casket—they’d had to have the flowers brought in from Miami because local florists refused to deliver arrangements to Negro funerals—

County sheriff departments and known Klan members were hardly forthcoming, and in central Florida the line between law enforcement and the KKK had often been indistinct. By the end of the 1940s it was completely blurred. “We’d go in and talk to someone in law enforcement,” Meech reported, “and they’d say, ‘what the hell are you investigating that for?’ He was only a nigger.”

The defense dared not to question in any way either the purity of the Flower of Southern Womanhood, however indelicately she might be represented by Norma Lee Padgett,

A woman’s chastity is the greatest thing on earth to her, and nothing in the world compares to it.”

In the summer of 1954, the outspoken Willis V. McCall was named a director of the National Association for the Advancement of White People, which devoted itself primarily to the advocacy of racial segregation.