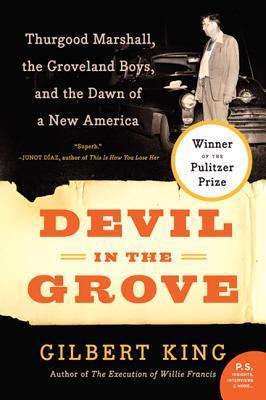

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Gilbert King

Read between

June 7 - June 18, 2023

From 1882 to 1930, Florida recorded more lynchings of black people (266) than any other state, and from 1900 to 1930, a per capita lynching rate twice that of Mississippi, Georgia, or Louisiana.

Jack E. Davis, a University of Florida history professor who studied racial violence in the South, concluded that “a black man had more risk of being lynched in Florida than any other place in the country.” Alarmingly, despite the shocking and heinous nature of the lynchings in Florida, the crimes and the cover-ups generated little attention, let alone outrage—beyond the black newspapers.

Henry Shepherd, who had long suffered the ire of his white neighbors, and finally their torch-lit violence, agreed. “I been told by a lot of people it was nothing but jealousy and jealousy is what it was,”

After World War I, dozens of Negro soldiers had been lynched in the South, some of them still wearing their uniforms, and in the summer of 1946 the lynchings of black veterans resumed with a vengeance. Fathers of black soldiers warned their sons not to come home in their uniforms because police had made a practice of searching and beating black military men. “If he had a picture of a white woman in his wallet, they’d kill him,” one Mississippi man related.

Oppressive heat, old Southern lawyers in red suspenders, whittling judges, a fearsome sheriff, and a crowd of racist, tobacco-stained crackers on the benches behind him—“it was,” Williams observed, “almost to me like a story that I was living through and these were caricatures that I was being exposed to.”

It all changed—and in his way, with the Groveland Boys, Marshall had helped to change it. “There is very little truth to the old refrain that one cannot legislate equality,” Marshall posited in a 1966 White House conference on civil rights. “Laws not only provide concrete benefits, they can even change the hearts of men—some men, anyhow—for good or evil.” In Groveland, Mabel Norris Reese had come round. So had Jesse Hunter. Governor LeRoy Collins had done the right thing. Maybe, too, that young juror with an honest face, the one who’d been listening so intently to Marshall’s summation at the

...more