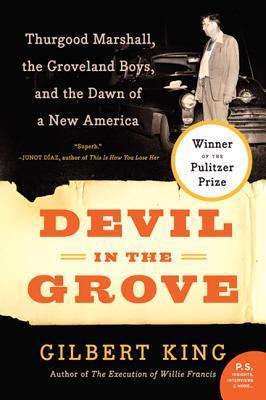

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Gilbert King

Read between

August 26 - September 2, 2020

To Marshall, the representation of powerless blacks falsely accused of capital crimes became his opportunity to prove that equality in courtrooms was every bit as vital to the American model of democracy as was the fight for equality in classrooms and in voting booths.

Marshall would later say, “There is very little truth in the old refrain that one cannot legislate equality. Laws not only provide concrete benefits, they can even change the hearts of men—some men, anyhow—for good or evil.”

The tradition of the rent party, which thrived during the Harlem Renaissance, continued into the forties out of economic necessity. Because famous clubs like Connie’s Inn and the Cotton Club did not allow black customers, and Small’s Paradise, though not segregated, had high door fees that ensured mostly upscale white audiences, much of the great live music at the time was not accessible to blacks.

Madame Stephanie St. Clair, known to most as “Queenie,” was purported to be the Numbers Queen of Harlem and, at one point, the richest black woman in America. In New York by way of Martinique, Madame St. Clair—abrasive, unsmiling, and tough as nails—had managed to withstand the violent efforts of Dutch Schultz and any other mobsters who’d tried to horn in on her gambling operations and territory.

“I wanted to do hard news,” Cunningham said, “and he [the Courier editor] started worrying about me and I said, ‘Well, I get killed somewhere it’s not your fault. Can’t nobody sue you ’cause you weren’t even there. Chicken!’

In Cash’s estimation, the Southern rape complex “had nothing immediately to do with sex,” but rather with the feeling among Southerners that if blacks were to advance beyond their severely circumscribed social station, they might “one day advance the whole way and lay claim to complete equality, including, specifically, the ever crucial right of marriage.”

In the landmark case Smith v. Allwright, Thurgood Marshall had argued before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1944 that it was unconstitutional for the state of Texas to ban blacks from voting in the Democratic Party’s primary. The Supreme Court agreed and overturned the party’s practice of all-white primaries, a ruling, Marshall noted, that was “a giant milestone in the progress of Negro Americans toward full citizenship.” He later assessed the Smith v. Allwright victory to be “the greatest one” of his career.